Things were moving very fast. On June 25, there was a very big public meeting attended by Jayaprakash Narayan at the Ramlila Grounds in Delhi. At the meeting Narayan said that Indira Gandhi should be forced to resign, the police and army should refuse to obey illegal orders and the people should surround her house. It is a moot question whether this eventuality could or could not have been met by the laws and regulations already in force. However, as far as I was personally concerned, I had no knowledge back then of some of the facts that I have described above. That same day, at about 6pm or so, I left office and walked back home unaware of any impending crisis. I think it was four in the morning when the RAX telephone (a special secret telephone connected to only a few selected people — ministers, some secretaries, etc.) began to ring. Lalit answered the phone and woke me up. The call was from the Prime Minister’s house and I was informed about an emergency meeting of the Cabinet — at 5 or 6am. I was also told that the ministers were being informed separately.

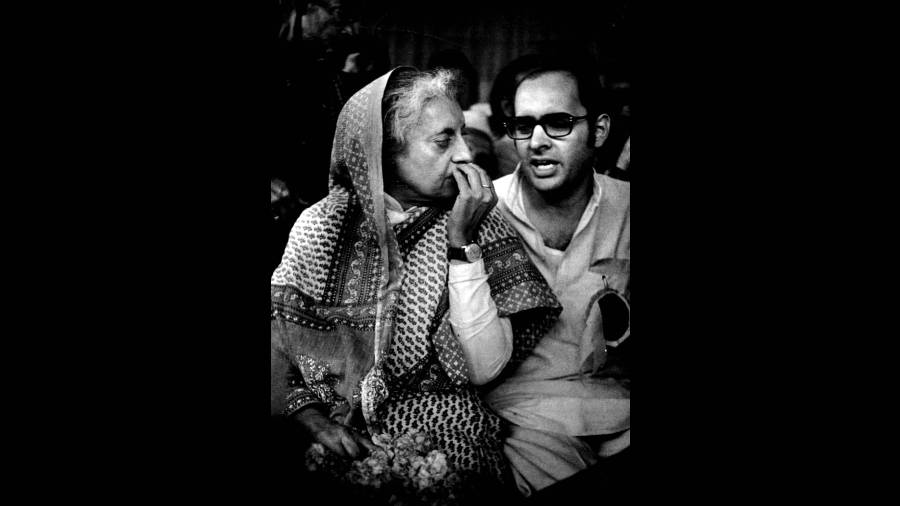

B.D. Pande File picture

I arrived at 1 Akbar Road a few minutes before time. I thought to myself that perhaps Indira Gandhi had decided to resign. Jagjivan Ram and Swaran Singh reached at the same time as I did. We were all equally clueless about the reason behind this sudden meeting. Y.B. Chavan arrived and shared with us the news about the arrest of Jayaprakash Narayan, Morarji Desai and some others. This news set everyone thinking. Soon thereafter, Mrs Gandhi was seen walking from 1 Safdarjung Road with Om Mehta and some others. Their faces showed that they had not slept the whole night. The Cabinet finally assembled and in a terse few words Mrs Gandhi announced that a proclamation of internal emergency had been promulgated by the President last night, several people had been arrested, and that she had decided that the disorders be put down by a firm hand. No minister said anything. She then asked me to call home secretary S.L. Khurana and ask him to come immediately. On arrival, he was handed over a copy of the proclamation and asked to take further action. The Cabinet had duly ratified the decision and the meeting soon dispersed.

It was later discovered that the said notification was taken to President Fakhruddin Ahmed the previous night and signed by him then. It was actually published in the morning, but was dated the previous day. At about 10 or 11 in the morning there was a meeting in the home secretary’s room to discuss the further course of action. At that meeting, Khurana read out the names of the dozens of people who had been arrested the previous night. It appeared that some BSF and air force planes were sent to various state capitals to carry some chief ministers and other designated people from Delhi. They had all been given lists of people to be arrested immediately. The ministers had called their chief secretaries and IGs of police and given them the lists along with orders to make the arrests immediately. The places where they were to be confined were also indicated therein. The ministers were also given instructions to add more names to these lists. Most of the names belonged to the Opposition, but included some dissident Congressmen like Chandra Shekhar, once a great supporter of Indira Gandhi and leader of what were called the Young Turks in the Congress(I).

Under the Emergency proclamation, fundamental rights, especially the right of habeas corpus had been suspended. We had a debate whether the full list of names of those arrested was to be given out. Most of the secretaries were in favour of doing this. P.N. Dhar said he would check with the Prime Minister, but she declined. Further, a press censorship would also be imposed to curb the reporting of the news concerning arrests. Someone remarked we were living in Idi Amin’s Uganda! The declaration of Emergency was not only ratified by the Cabinet, it was also voted by both houses of Parliament. The legality was upheld by the Supreme Court in a writ petition. Thus, both constitutionally and otherwise, the Emergency was valid in law.

Although the initial reaction of the people was one of shock or disbelief, yet for the first six months there was general approval… Government offices functioned better, corruption was less, many long-standing diffi-culties of the people were removed and railways, following the collapse of the rail strike, functioned much more efficiently. Some people, with older memories began to compare the situation with Mussolini’s Italy. Some programmes of development were presented in new bottles, the Prime Minister’s 20-point programme and Sanjay Gandhi’s five-point programme.

But things did not rest there. After the Emergency proclamation, Parliament amended the election law, the Representation of People’s Act, retrospectively nullifying the high court decision on the election petition. It also amended the rule regarding appeals, so that the Supreme Court had to set aside the order of the high court judge. The Constitution was amended to increase the term of the Parliament and state Assemblies from five to six years, as elections to the state Assemblies were due shortly and the Congress(I) was not willing to face them.

All these measures were resented by the people. Then two programmes of Sanjay Gandhi were enforced with vigour — the first related to demolition of unauthorised structures in various cities including Delhi, and the other was the family planning programme. Both these caused widespread resentment. More so with the family planning programme as it was spread far and wide into the villages.

At this time Mrs Gandhi also began making statements asking for commitment on the part of officers. The question that followed was, commitment to what — the Constitution of India or the person of the Prime Minister? While publicly it was said to be the former, in the case of several important and sensitive appointments it was meant to be the latter. A few cases that came my way gave me an inkling. Proposals were made for the appointment of some officers to certain posts, but the Prime Minister’s final orders were not received, even though reminders and telephonic messages were sent her way.

Then one day the officers were rung up and called to see her. They went and were told that Sanjay Gandhi would meet them. The one or two who gave an undertaking of loyalty and were found fit had their appointment proposals approved. For the rest, it was reversed. The officers whose proposals were not approved came and told me about their interviews. In some cases the ministers were asked by the Prime Minister’s Secretariat to withdraw the file and recommend others. This also caused great resentment among the civil servants. Some of them went out of their way to what may be called ‘out-Herod Herod’. Among them, then Lt Governor of Delhi Krishan Chand, and Jagmohan, then in the Delhi Development Authority, come to mind.

Krishan Chand could not survive the collapse of Indira Gandhi’s Government and committed suicide soon thereafter. It was one of the most tragic cases of being too loyal.

Reproduced with permission from In the Service of Free India: Memoir of a Civil Servant; Published by Speaking Tiger Books