The tendency of the incumbent regime to single out Jawaharlal Nehru to blame for just about any of their troubles is now legendary. It has not gone unnoticed that in its criticism of dynastic politics, the regime does not attack

Indira Gandhi with similar single-mindedness. The Emergency is a blot on independent India, an exceptional disruption of democracy that dealt indelible blows to our democratic polity and aspirations and set terrible precedents for later tyrants to mimic. Is this legacy of Indira Gandhi treated with kid gloves by the current regime because Emergency is their favoured model without even the declaration of it?

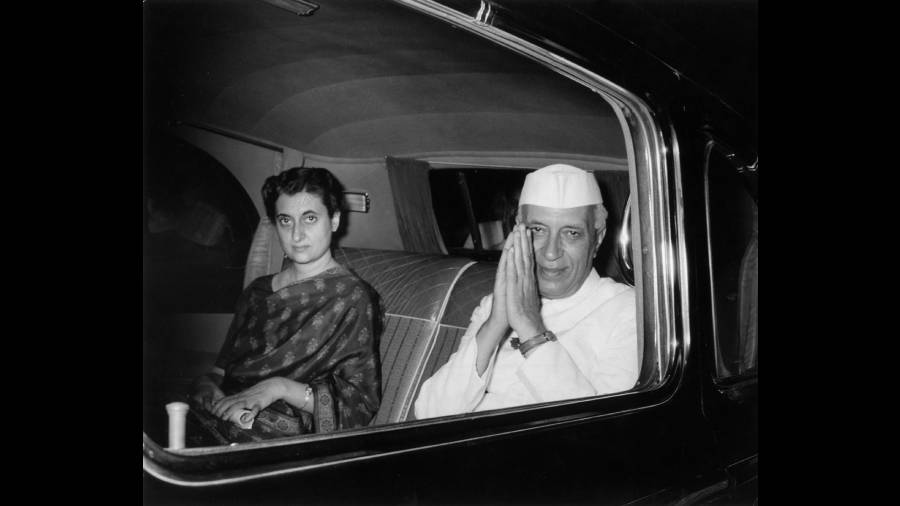

The personality and conduct of Indira Gandhi was often at odds with what she professed to believe in. These contradictions are apparent when you examine her closely in different phases of her life — a young person growing in a household full of freedom fighters, as Nehru’s daughter while being partner of Feroz Gandhi, one of Nehru’s most vocal critics in Parliament, going from being the heir apparent in the Congress to splitting it. Her imperious political style and her close self-identification with India during the Emergency gave birth to an alarming authoritarianism and left our democracy mangled.

It bears pointing out that by contrast Nehru’s ideas about Indian democracy were not based on an individual quirk of personality. They were based on a principled faith that the foundations of a multicultural democracy lie in strengthening civil liberties and instituting processes that ensured social justice and harmony, and not on overconfidence in his personal ability to lead India. In this Nehru was also being mindful of the serious warning about the role of “Bhakti” sounded by Ambedkar in his final address to the Constituent Assembly. Ambedkar had clearly said that the path of hero worship in politics could lead to eventual degradation of democracy and pave the way for authoritarianism.

Indira Gandhi’s “Emergency years” are probably inspirational to the present regime; and the stiffest challenge to their project to reimagine India as “New” comes from the Nehruvian idea of democracy and democratic functioning. Nehruvian ideals and his legacy command a deep and pervasive influence on the people of this country including his critics. “The Gentle Colossus” as he was called by veteran Communist parliamentarian Hiren Mukherjee, Jawaharlal Nehru embodies much that is grand and laudable about Indian democracy.

In the last parliamentary session, the government disallowed questions on topics of national importance such as widespread surveillance and the farm laws. The decision to restrict Question Hour in the monsoon session of 2020 was shamelessly undemocratic. Narendra Modi has rarely answered questions on the departments and ministries held by him. His silence on the issues of importance and his absences from parliamentary debates remain a stark reminder of deteriorating democracy in India.

Contrast this to Nehru, who, despite having a staggering majority in Parliament, never brushed aside the Opposition and gave dissent its due space. He did not shy away from uncomfortable questions and sat through the debates and interventions meant to criticise him. For instance, during the much-condemned China fiasco, Nehru made as many as 32 statements and interventions on China on the floor of the Parliament. He was present in Parliament even on days that the Prime Minister’s business was not listed, and participated in debates that did not strictly relate to the working of his department.

Putting into practice the ideas and values of the leadership of the newly independent India, Nehru took on the unique task of building a nation rather than merely administering it. It is entirely conceivable that when Prime Minister Narendra Modi told Parliament in 2018 that rich democratic traditions have long been a part of Indian culture and that India does not owe democracy to its first Prime Minister, he was merely revealing his blinkered understanding of the past.

Jawaharlal Nehru was a true democrat who laid the strong foundations on which we stand today and pride ourselves on being the world’s biggest democracy. He deeply believed that Indians could not merely adopt democracy; they had to develop it. Nehru was at pains to underline that democracies had no special claim to survival. Democracies are as likely to fail or succeed as any other political institution. In this, he appeared to wholeheartedly agree with his venerable colleague, B.R. Ambedkar who had argued in his last address to the Constituent Assembly that while the Constitution provides the blueprint for the workings of the State, it is up to the people to “carry out their wishes and their politics”.

A government unaccountable to Parliament seems to be knocking down this far from perfect, yet painstakingly built, democratic ethos of our country. Today, regrettably, it would not be exaggeration to say that India is a functional electoral democracy found wanting in the very elements that make for vibrant and open democracies — inclusion, deliberation and accountability.

In a letter dated March 1, 1950, Nehru wrote, “Loyalty is not produced to order by fear. It comes as a natural growth from circumstances that make loyalty not only a sentiment which appeals to one but also profitable in the long run”. In the same letter, he offered long-term policy solutions to consolidate India by making all minorities in the country at home. Nehru warned that even though India would survive any attack on its secular moral characteristic, she would be grievously wounded and take a long time to recover.

The contentious Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) passed in the midst of protests defies this vision of inclusivity. Constitutional experts as well as international watch bodies have observed that the amended law will cause Muslims to face exclusion. We have failed to learn the right lessons from the experience in Assam of the consequences of such policies.

There is no denying that democratic forces in India have found themselves under strain in recent times. It is inevitable that the dark memories of Emergency have been invoked, as we see those very practices being normalised today. Activists, journalists, politicians, and students are being threatened through systemic misuse of institutions. The media was officially censored for 21 months following the imposition of Emergency in 1975. Today we have ended up largely with a media that is expert at falsification, misrepresentation and distortion of reality. On the other hand, media entities that show autonomy find staggering curbs imposed on their freedoms through dubious methods, without any formal suspension of rights. Central agencies are being used as tools to scare those who dare to openly dissent and question. Arbitrary Internet shutdowns, restrictive IT guidelines and the proposed changes in the Cinematograph (Amendment) Bill are just some of the actions of the NDA government that clearly tell us that control over expression and opinion remains it top priority. Imposing sedition laws without any due process has been deeply concerning, to the extent that a sitting judge had to remark, “The offence of sedition cannot be invoked to minister to the wounded vanity of the governments.” Vanity is probably another quality that holds the current regime in thrall of Indira Gandhi.

The writer is an RJD member of the Rajya Sabha and teaches at Delhi University