While Lata Ghosh was wandering about the flat that, in an alternate universe, she and Aarjoe Choudhury might have filled with beautiful unnecessary things, alongside the flotsam and jetsam of coupledom, old tax receipts and inherited china, filmmaker Ronny Banerjee was holed up at home, in Salt Lake, attempting to cope with the several crises that had cropped up in his universe. Not his universe, to be accurate, the universe —multiverse? — housing Mondira and Srijon Shekhar and Trina and Ryan, his principals, who were probably feeling all stranded and breathless, now that so many black holes had emerged in their lives within the final draft of Ronny’s script. The final script that still lived and breathed, unfortunately, only in Ronny’s head.

It was half-past 10 in the morning. The meeting with the producers was at five. Despite the acidity, several cups of tea had been consumed already.

Scattered on Ronny’s bed were drafts of the script, several notebooks, the little biography of J.C. Bose he was using for reference and which, invariably, made him very cranky — why on earth wasn’t there a decent, mainstream biography of one of the greatest scientists of the world?! — and his well-thumbed volumes of Sunil Gangopadhyay’s Pratham Alo, a novel that brought to luminous life the world of J.C. Bose and Tagore. Should Rabindranath have a cameo in the film now that Acharya was a protagonist?

Ronny sighed and looked at the time.

This thing was running away from him.

Like a lot of artists, Ronny had a complicated relationship with deadlines. They often brought the elusive muse scurrying to his window in their wake — and some of the most intractable plot problems had been solved by him at the eleventh hour, when the deadlines were truly upon him. But on a few occasions, as now, they chafed against his creative spirit and blocked him up completely. He pushed and he pushed. Nothing.

By panicking, Bobby was making it worse.

Apparently, at the last meeting, when he did not show up, Nikhil had been marginally offended. Was Ronny becoming a flake? Nikhil had asked Bobby. Privately, Ronny was certain. (Nikhil Maheshwari was his friend for crying out loud!) But Bobby had reported it to him dramatically, widening her eyes to make her point. “I really think you should take the next meeting seriously, Ronnyda,” she’d hissed.

This wedding business had made Bobby cross — Ronny imagined her relatives were badgering her endlessly about settling down, now that even AJ, the baby of the family, was married — and it made her hit the panic button on Shomoy harder than ever. She wanted Ronny to narrate the new script to Nikhil this evening. “What?” he’d spluttered. “If not the whole script, then, at the very least, you should clearly demarcate the differences between the old script and the new,” she’d replied.

As though Ronny had it all figured out and simply needed to draw up two columns on a white board: old script, new script.

Bobby would come by 12, she’d said, to prep with him and decide upon specific answers to the questions Nikhil and his team would pose: How many more days of shooting would it entail? How many more actors? Instead of Shaarani Sen, who? If it’s not Shaarani Sen, how can we be sure this gambit will work? Babluda is a great actor, but he’s not a star! And, most importantly, how significantly will all this impact the budget?

God, Bobby would arrive soon, and, within minutes, her face would be lit in disappointment. (“Tumi aamaay assure korechhile Ronnyda that I could enjoy AJ’s wedding and not worry about the script, that you would be on the job!”)

Are other filmmakers as terrified of their assistants’ disapproval?

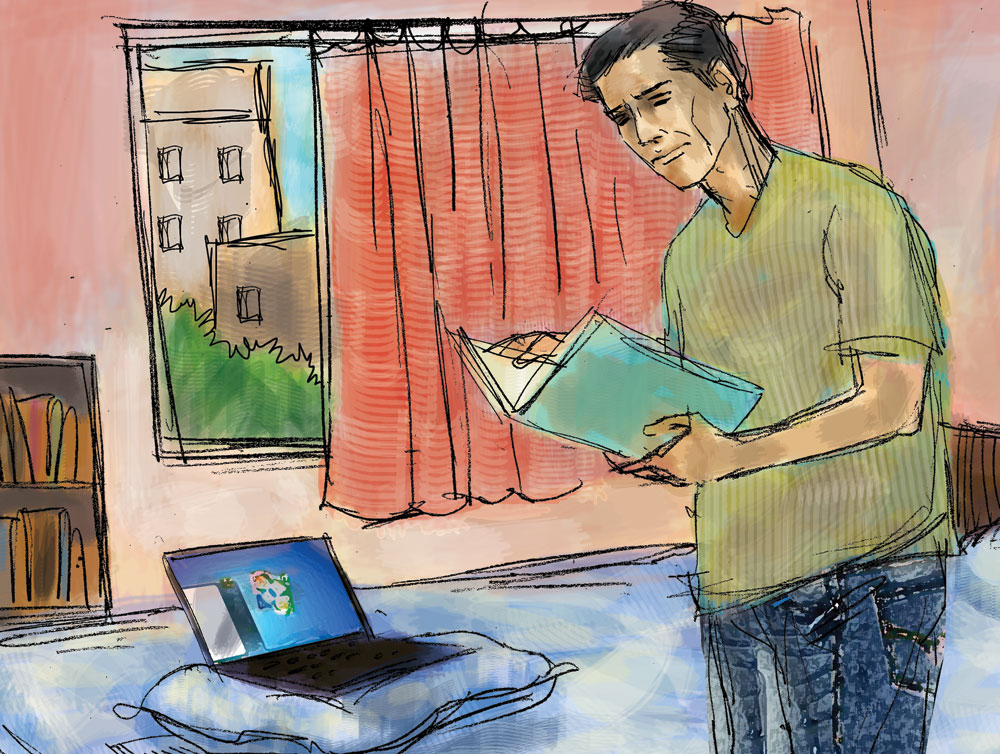

Absent-mindedly, Ronny moved his laptop, hot already, to the pillow next to him and left the bed. He arched his back, indulged in a few lunges, dropped onto the mat and gave 20 push-ups. Then he walked vaguely around the room, going up to his desk in the converted study (it used to be a balcony) but not exactly expecting any epiphanies. The desk was a dump. He picked up an old timepiece from his desk, one that had stopped months ago, and glared for a while at the square of clean wood that instantly appeared in the surrounding dust.

Circling back to his bed, Ronny picked up one of the oldest Shomoy notebooks — for each film he had over 20 of these unlined notebooks — where he’d sketched the earliest scenes. As a devotee of Satyajit Ray, Ronny liked to follow Ray’s techniques, even though most people thought he was possibly going too far with the notebooks and the pictures. But there was something very therapeutic in the act of sketching his characters, Ronny felt. They revealed intimate details about themselves when Ronny prodded them gently with his pencil.

As he leafed through the notebook, Ronny’s mood improved, his breathing became even, he even asked for breakfast to be sent. Then, at some point, a half-bitten buttered toast in one hand, he realised that his Trina and his Mondira both looked far more like Charulata Ghosh than Pragya Paramita Sen. How had he not seen this before?

***

“We need more hits,” Hem Shankar Tiwari shook his head unhappily.

Hem and Aaduri were eating an early lunch at the small restaurant close to office and dissecting last evening’s meeting with the boss and super-boss. Apparently, the website was burning cash and needed five million hits a month asap. Like, by the end of the week, no pressure. After the meeting, they’d rushed to Molly’s sangeet in response to Lata’s messages, and they’d had no time to go over the minutes. This afternoon, though, Aaduri had called for a team meeting.

“Calm down, Hem,” Aaduri replied, dunking her mini idli in coconut chutney. “Management meetings are always like that. They keep asking for impossibles and you keep defending your turf. It’s fine.”

“But we do need more hits. Look at the other sites we are competing with. They have at least one breakout story every week. One story that goes giga. The old lady talking to Alexa in Bhojpuri? The dog who married the cat? The little girl stealing that pink umbrella?”

“Yes, yes,” Aaduri said vaguely. She did not click on half the links Hem sent her.

“We totally need liquid content like this. That Pragya Sen Insta story did rather well. Do you think Tiana can shoot videos? You know how Kareena Kapoor’s gym routine breaks the Internet once in a while? Maybe we could get Tiana to grab a camera and make little videos of Pragya’s fitness regimen.”

“Pragya is not Kareena Kapoor, let me remind you Hem. I think we should redesignate you as video scout,” Aaduri said, looking around herself, “After we return from Jamshedpur. And don’t think for a second I don’t know why you want all these ridiculous fitness videos. Not for the website.”

“Curator,” Hem clarified. “Not scout. And please. Fitness boomerangs are the rage, that’s all. I don’t like Pragya’s body type myself. I am much more of an old-fashioned Hindi belt type. Find Pragya too thin. Are you looking for your phone? It’s charging in that corner.”

“Oh yes,” Aaduri remembered, now motioning at the waiter to fetch it. “Ever since I took this millennial job, I’ve become addicted to my phone.”

“Why are we going to Jamshedpur?” Hem asked.

But by then, Aaduri had her phone back in her hands and forgot to reply.

“Your friend Lata Ghosh,” she finally looked up at Hem, “Has sent me a poem. It’s by Wendy Cope. Care to hear it, Hem Ilahabadi? It’s sort of self-explanatory though. Bloody men are like bloody buses —/ You wait for about a year/ As soon as one approaches your stop./ Two or three others appear.”

Hem started laughing.

“She is bloody bewitching, isn’t she?” Aaduri smiled.

After paying off the bill, they started to descend the stairs and Aaduri now recited, from memory, the second verse. After all, she’d introduced Lata to Wendy Cope.

“You look at them flashing their indicators,/ Offering you a ride./You’re trying to read the destinations,/ You haven’t much time to decide.”

Outside the office, the street was as busy as ever.

In a warm spot of sun, Aaduri lit a cigarette and looked philosophically at a passing cloud. By then, Hem had pulled out the poem via Google and, in his formal manner and the faint trace of accent that added a layer of charm to all his pronouncements, he now read off his phone:

“If you make a mistake, there is no turning back./ Jump off, and you’ll stand there and gaze/ While the cars and the taxis and lorries go by/ And the minutes, the hours, the days.”

(To be continued)

Recap: Pixie’s email saying that she cannot attend Molly’s wedding turns into a litany of woes. Lata, meanwhile, meets ex-husband Aarjoe in New Town to close some unfinished business — arrange to sell off a flat that they had bought together in a swish condominium.