Book name: The Murderer, The Monarch and The Fakir: A New Investigation of Mahatma Gandhi’s Assassination

Author name: By Appu Esthose Suresh and Priyanka Kotamraju

Publisher: HarperCollins

Price: Rs 399

One triumph and two tragedies accompanied the culmination of the British raj in India. The triumph was that India became free from colonial rule. The first tragedy was India’s Partition: the Muslim League’s poisonous ‘Two Nation theory’, which created Pakistan and the genocide of over a million innocent Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs that midwifed it. The second tragedy, five months later, was the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest apostle of truth and nonviolence the world has seen in modern times.

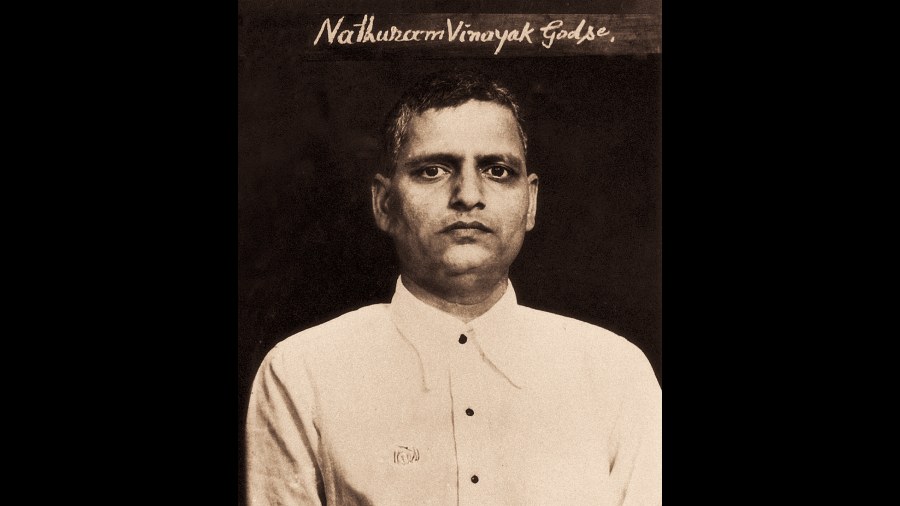

The identity of the hand that killed Gandhi was known the same day — Nathuram Godse, a Hindu extremist from Maharashtra. The mind that inspired and guided the hand — V.D. Savarkar, the foremost leader of the Hindu Mahasabha — was revealed in the course of the investigation. This book by two journalists is timely because both Godse and Savarkar have received a new lease of life since the advent of Narendra Modi’s rule in 2014. Godse is being eulogized publicly by a section of the sangh parivar like never before. And Savarkar, the ideologue of Hindutva, the political philosophy of the Bharatiya Janata Party under Modi and Amit Shah, is projected as a national hero.

The book convincingly highlights the Godse-Savarkar nexus. Whereas Godse was hanged, the trial court acquitted Savarkar for lack of sufficient evidence. The acquittal was the outcome — also a proof — of a botched-up investigation and a non-rigorous trial. Gajanan Damle and Appa Kasar, Savarkar’s secretary and bodyguard, respectively, were not brought in as witnesses even though the duo had given statements to the police that Godse and his accomplice, Narayan Apte, had visited their leader’s house in Bombay “twice or thrice” after the failed attempt by Madanlal Pahwa on the Mahatma’s life on January 20, 1948 — that is, just ten days before the second, successful, attempt. When the Jeevan Lal Kapur Commission re-examined the conspiracy in the late 1960s, it came to an unambiguous conclusion: “All these facts taken together were destructive of any theory other than the conspiracy to murder by Savarkar and his group.”

Most of the facts presented in the book have already appeared in previous works on the subject. The authors have mentioned The Men Who Killed Gandhi by Manohar Malgonkar and the report of the Kapur Commission but they fail to acknowledge two other authoritative books — one is Let’s Kill Gandhi: A Chronicle of His Last Days, the Conspiracy, Murder, Investigation, Trials and The Kapur Commission by Tushar Gandhi; the other is The Story of the Red Fort Trial, 1948-49 by P.L. Inamdar, the lawyer who secured the acquittal of D.S. Parchure, a Savarkarite leader from Gwalior, who provided the Beretta gun that Godse used to kill Gandhi. Letting Parchure go scot-free is another proof of the slipshod trial.

The authors’ claim about “A New Investigation” into Gandhi’s assassination pertains to the role of the “Monarch” — Maharaja Tej Singh of Alwar, a princely state in Rajasthan, and his rabidly anti-Gandhi prime minister, N.B. Khare, who was also a staunch supporter of Savarkar. Om Baba, a ‘godman’ in Alwar, had announced that “Gandhi was dead at least two hours before the assassination.” He and Pahwa had “shared a room” in the office of the Hindu Mahasabha in Delhi on January 19, the night before the latter detonated a bomb at Birla House where the Mahatma was having his prayer meeting. Godse had visited Alwar and knew Khare well. Khare and Parchure were also known to each other. The book thus establishes the Savarkar-Khare-Parchure-Godse link in the heinous crime.

What could have been the Maharaja’s motive? The answer lies in Savarkar’s own motive. Savarkar wanted the princely states ruled by Hindu rajas to reject the Gandhi-Nehru-Patel plan to integrate them into independent India. He wrote, “The Hindu Mahasabha has declared that the Hindu states are centres of Hindu power.” This view was echoed by the Maharaja of Alwar: “It is the forefathers of the present rulers who have saved India from Moslem domination. The same task lies ahead and we call upon the Hindu Princes to play their rightful role and save the Hindu Rashtra from extinction.” The authors conclude the chapter, “Alwar and the Princely Affair”, with this remark: “If the Gandhi assassination probe team was looking for a motive, here it was — revenge for a fatal blow inflicted by Gandhi to a more-than-fifty-year-long grand project of assuming power when the British departure created a vacuum.”

The book’s one avoidable flaw is that it devotes nearly half of its already brief space to contemporary issues like the CAA-NRC controversy which, although linked to Savarkar’s divisive Hindutva ideology, are only remotely related to Gandhi’s assassination. Nevertheless, it is a welcome new addition to the literature on a subject India must never forget — and never allow to be falsified by the neo-Savarkarites now ruling the nation.