Writers, broadly speaking, are creatures of strange habits. Agatha Christie would ponder murder plots while munching on apples in her bathtub; Walter Scott composed poetry on horseback; Truman Capote wouldn’t begin or finish a piece of work on a Friday. The loved ones of writers had to put up with these eccentricities and more. Some authors even managed to find companionship in stationery.

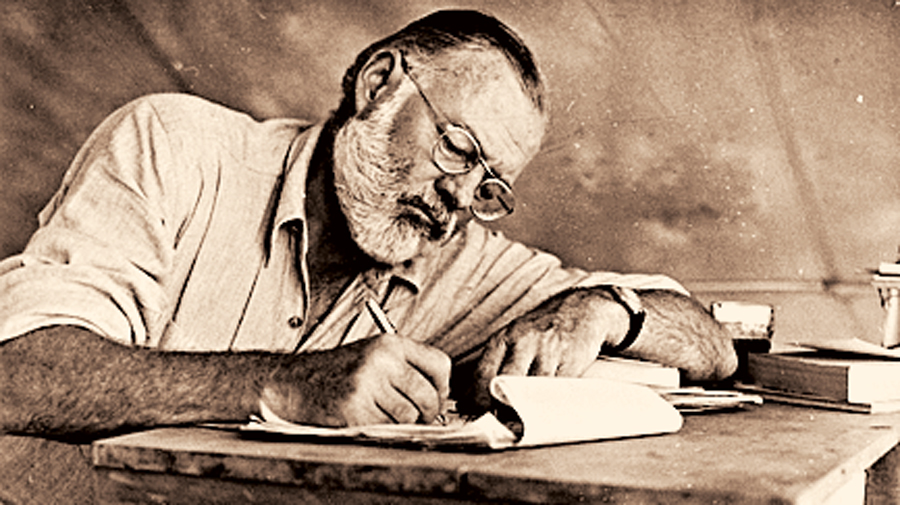

John Steinbeck — he died this month — expressed his wrath against the world through not only the content of his books but also aggressive scribbling. Steinbeck was known to have burned through some 60 pencils a day while penning the Pulitzer-winning The Grapes of Wrath. The pencil was not a friend to Steinbeck alone; it got Ernest Hemingway through his days of struggle as a writer as well. Although Hemingway would use the pen and the typewriter too, he favoured pencils, sharpening them with care whenever he got a moment’s break from writing. “Wearing down seven number-two pencils is a good day’s work,” he once said.

For James Joyce, the ritual of writing was as unusual — and colourful — as his writing style. Joyce wrote parts of Finnegan’s Wake on large pieces of cardboard in bright red crayon, using different shades to mark and make notes in his scripts during revisions. Colours were of great importance to Alexander Dumas, although for completely different reasons. Joyce could attribute his habit to his failing vision; for Dumas, it was just a quirk: he would write poetry on yellow sheets, articles on pink, and novels on blue. Once, when he had to resort to cream-coloured sheets after running out of blue paper, he was convinced that his work had suffered on account of the mismatched colour codes.

It would be unfair to paint all authors with the same brush. When inspiration strikes, there is hardly time to pick and choose. Margaret Atwood puts this plainly — “I’d write with lipstick if there were nothing else.” Similarly, note cards and index cards are responsible for some of the best works by Joseph Heller and Vladimir Nabokov seeing the light of day — those were the objects that they scribbled on during travel. William Faulkner went a step further. He scrawled out the outline of his novel, A Fable, on the walls of his home in Mississippi. All the world’s, evidently, a blank script for the writer.

But as Hilary Mantel points out, “[t]here is persistent confusion between writing and writing things down” — the first involves the creative exercise of churning ideas in the mind whereas the second refers to recording them. The tools of the trade, unlike the layman’s assumption, do not necessarily serve the second purpose alone. Ideas, in their nascent stage, are often muddled; it is writing — “the act of making paper dirty”, as Neil Gaiman would say — that disentangles them and puts them in order. Is that the reason why the likes of Joyce Carol Oates, Amy Tan, Jhumpa Lahiri, prefer to write their drafts by hand even though they have access to digital technology?

A thin line separates creativity from madness. Without coherence, jumbled ideas could well be the ramblings of a madman. This is what makes stationery indispensable to writers: they keep their imagination in order.