Sujit Saraf is a riot at parties and very critical yet appreciative of his Marwari family members in Calcutta. The DSC Prize for South Asian Literature nominee from Silicon Valley was in town to attend the Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet in association with The Telegraph. Just before he landed in the city where he has spent many a summer vacations at his “naani’r bari”, t2 had a long chat with him about the history behind his book Harilal & Sons, what inspires him to write and his theatre group NAATAK, whose productions have been entertaining Indians in the Valley for the last 25 years. Excerpts...

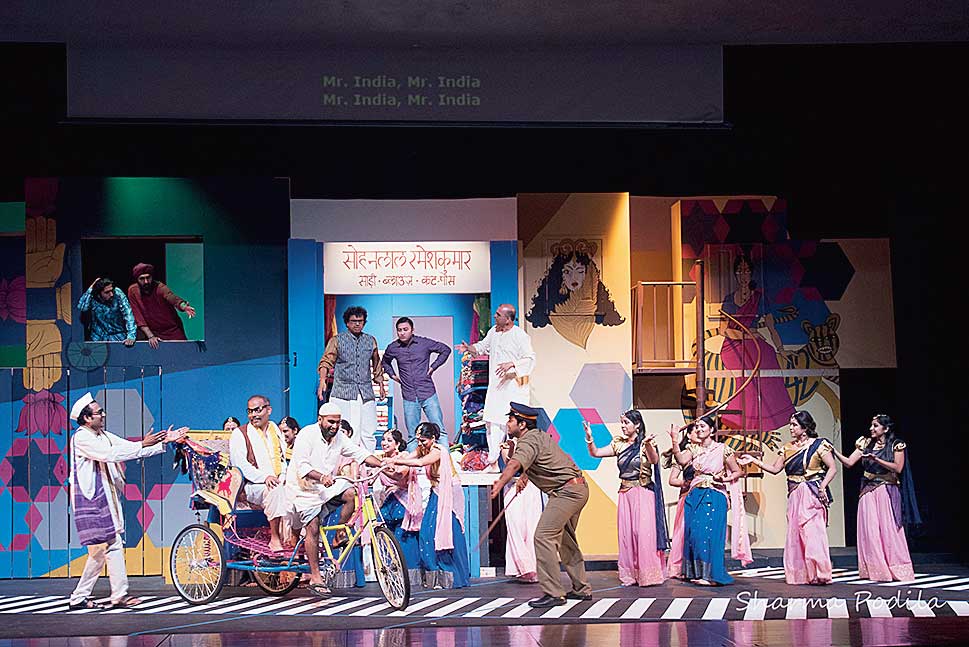

A scene from Mister India, a musical written and directed by Saraf, for NAATAK. This was a stage adaptation (in Hindi) of his novel The Peacock Throne. Picture: Sharma Podila

When did you know you wanted to be a writer? What inspired you to?

I grew up in a small town in Bihar that did not have good “English medium” schools, so I was sent to a boarding school run by Irish Catholic missionaries in the hills of Darjeeling where, my father was told, “they force you to speak in English”. His information was correct — those caught using Hindi, Nepali or Bengali were subjected to “benders”. I came home for Easter holidays (having just learnt what “Easter” was) with English phrases and the lyrics of an English song on my lips. Apparently, that was my first step into the world of Indian writing in English.

The next step was more substantive. Every Wednesday, the missionaries decreed a reading session of two hours during which we were forced to read instead of doing homework. This made no sense —what was the point of reading stories that weren’t even true? I was force-fed Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, Tom Swift, Biggles, Wodehouse, “Hath not a Jew eyes?” and so on. Over the years, this gruel began to taste good, and I began to devour every book I could lay my hands on. All this reading led to the natural desire that I should write something myself. That was when, in high school, I became a writer, at least in my own mind, and I guess I have the missionaries to thank.

You have been an NRI for a while now. How difficult is it writing about India from so far away?

There is indeed some dissonance in living in California and writing about a man on a bullock cart rolling through the beels of Bangladesh. I have wondered, at times, if this whole business of Indians living in the West and writing about India (primarily for the West) is a bit of a scam. I remember sitting in the lobby of the Oberoi Amarvilas in Agra, speaking to a dozen French journalists about my novel The Peacock Throne. I spoke of sodomy in the lanes behind Jama Masjid, Bangladeshi immigrants, the riots of 1984, the Mandal commission protests. Beyond the glass walls was the Taj, bathed in a warm glow; around me, immeasurable opulence; half a mile away, the filth of the “real India”. I was aware of the dissonance, and perhaps the hypocrisy.

But it also occurs to me that those who live in Delhi or Calcutta hardly live in the India of my small town in Bihar, and those who live in my small town in Bihar hardly know what a beach in Goa looks like. India is a complex country; Indians are an ancient people. How can a Delhi-based writer claim to understand the Bihari men who lug soap cartons in my brother’s godowns in Bihar? I’ve grown up there, I visit often, and I perhaps see more “real India” than India-based writers ever will. Who can lay claim to the “real India”?

Overall, I like to think that something is lost — authenticity that comes with immersion — but something is gained — perspective.

What kind of research went into Harilal & Sons?

My grandfather Hiralal Saraf was 55 when my father — his youngest son — was born, and I am my father’s youngest son, so Hiralal was long dead by the time I was born. Because Hiralal married twice and had nine children survive into adulthood, his oldest sons were old enough to be fathers to his youngest son, my father. I have first-cousins who are older than my father.

One of these, Chiranji Lal, had the foresight to record an interview with Hiralal before he died in 1960. About 15 years ago, Chiranji Lal presented me with a copy of this cassette tape. Speaking in a voice ravaged by throat cancer — which was to kill him shortly after — Hiralal speaks, in a form of Marwari I struggled to understand, of leaving Shekhavati (in modern-day Rajasthan) at the age of 12, going to Calcutta and then Bogra in East Bengal. He speaks of himself, not of Marwaris in general, and certainly not of Marwaris placed in a changing India, but I knew right away what I would write — not a family history, not a history of Marwaris or even Hindus or India, but a tale of displacement and conservatism. Armed with introductions from Chiranji Lal, I travelled to Bangladesh, Mumbai, Rajasthan, Delhi, and wherever I could locate living members of my extended family.

I was welcomed into 100-year old homes in Shekhavati villages dotted with khejra trees. Old trunks were pulled out and opened to reveal coins featuring George V, meals of daal baati were lovingly prepared. In faltering voices, men and women in their 80s recorded — on my iPod, which now seems quaint — their personal histories. Most were unlettered. Their recollections had no dates, no wider historical context. The women had never stepped out of their homes; the men knew little beyond their trade. Most had never seen a white man while growing up in British India, and their recollection of “life as lived” was a list of uncles and aunts, weddings, births and deaths, as if all history were personal. Along the way, I unearthed family secrets and resentments and property disputes, and the prejudices, hopes and fears of my people, as well as their great disorientation in a world changing around them, all of which I poured into the person of Harilal in the novel.

Who were you writing for when you thought of Harilal & Sons?

I did not write Harilal & Sons for Harilal’s sons, most of whom can’t read a book in English. I thought first of a western reader and then the English-educated Indian reader. That is the oddity of “Indian writing in English” — those who feature in our stories often cannot read us, those who read us rarely feature in our stories.

What is your writing process like, especially with a full-time job?

I am an engineer and a scientist; I write like one. The whole book is written out in my head before I commit a word to paper.

The act of typing it out is mere manual labour. As for the day job, I have been fortunate to have jobs that offer much flexibility.

From engineering to the arts which included theatre and literature — what was the journey like?

I think there was no journey at all. I have always fancied myself a writer. Unfortunately, the world does not often agree.

Tell us a little about your theatre society and what you aim to achieve with it.

In 1995, I was doing my Ph.D at Berkeley and a close friend was doing his at Stanford. We had done some theatre as students at IIT Delhi. Because Berkeley and Stanford are only 30 miles apart, we started a theatre company, NAATAK, to stage Indian plays in the San Francisco area. Over 23 years, NAATAK has grown to become perhaps the largest Indian theatre company in the US. We stage four to six productions every year in Hindi, English, Tamil, Bengali, Gujarati and Marathi. Tens of thousands watch us every year, and our members — whose day jobs are in the usual bay area companies like Apple, Google, Facebook, SAP, IBM — have now been part of NAATAK for so long that they cannot imagine their lives without it.

I like to think that NAATAK is a jewel in the cultural landscape of Silicon Valley. And I think it will go on forever, long after I have moved on, if I ever move on.

What can we expect next from your table?

I am about to finish a novel that marries my love of science with my curiosity about human nature. It is part science fiction and part Silicon Valley parable, populated by venture capitalists, start-ups, IPOs, astonishing wealth and hubris. It describes the greatest engineering project ever conceived by humanity and is rife with terms like “disruption” and “step change”. It is, finally, my Silicon Valley novel, after having lived there for 25 years.

In September this year, I will write and direct Gandhi, a grand stage musical chronicling Gandhi’s life, to coincide with the 150th anniversary of his birth. This will be NAATAK’s largest production in 24 years.

Do you follow the Indian theatre space? If yes, what do you think of it?

Aside from exchanges with a few theatre companies in Delhi that sometimes stage my plays, I am largely ignorant of it.

Who do you look at for inspiration when it comes to writing?

I read a lot, as anyone who presumes to write should. I also spend much time in argument, because the more you argue the better you write, I think. The people I look to for inspiration are those who disagree.

How did it feel being nominated for an award like the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature?

Flattered.