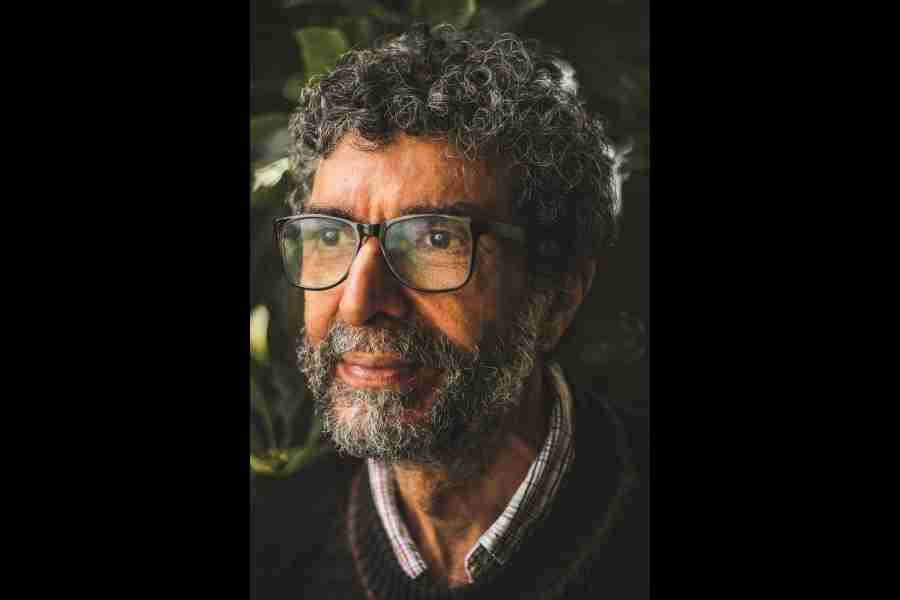

Cyrus Mistry is one of the first postcolonial storytellers about the Parsi community who grew up in Bombay but now lives in Kodaikanal. The move was initiated by, first, a moderately severe entanglement with multiple sclerosis of which he had frequent episodes while staying in Bombay, and, two, the need to find a good school for their son, Rushad who, after initial misgivings, was delighted by Cyrus and Jill’s decision to relocate. Mistry’s new edition of Doongaji House published by Aleph includes the unpublished and unperformed powerful play A Flowering of Disorder. A published writer since he was 21, Mistry is a winner of the DSC Prize, the Sahitya Akademi Award and a slew of other literary honours. His readers swear by his verisimilitude and vivid representations of Parsi life in his tales. Straddling two genres — theatre and fiction — he brings an original vision that draws his rich and assertive narratives. Mistry is currently at work on a new book that will look closely at the Indian Independence. While expectedly tightlipped about that particular project, he spoke freely with t2oS about other things about life and writing. Excerpts.

What are your earliest memories? Where did you grow up? What was Bombay like?

I grew up in a middle-class Parsi family, with two elder brothers and a younger sister, all talented in their own ways. But one thing that we definitely owe our parents was our love for music. My father was an amateur violinist. Before he became a famous writer, brother Rohinton was a very popular singer at the college level who strummed guitar and simultaneously played the harmonica (Bob Dylan-style) on a harness he had himself created for the blowing instrument from our rusty Meccano set. I almost became a classical pianist instead of a writer, before I realised I just didn’t have the discipline and hours of practice that persuasion called for. It was marvelous growing up in the Bombay of those days, taking the BEST public transport bus to school and back, much less oppressively crowded, for one thing.

Were you already making tracks with your composition, essays and did you write or perform in school theatre competitions?

Not really essays or school compositions. I was more obsessed with wanting to become a ‘composer’ of music in the Western classical style. I had written a couple of pieces for piano and even one movement of a sonata for violin and piano which was performed by a friend before a small public gathering under the auspices of the Bombay School of Music. I also won a prize for composition of two piano pieces when I was still at school. But I suspect that was because I was the only competitor who had enrolled for the contest!

Mistry wrote his first book of plays Doongaji House, when he was 21 and it won the Sultan Padamsee Award for Playwriting in 1978. It is a story about a house that no longer exists as a home for Piroja and Hormusji. The story is also about the infirm and marginalised members of the Parsi community, who are still great repositories of Western classical music traditions and making good cuisine — of which the violin and dabbas are symbolic.

Who were/are the writerswho inspire you?

The overwhelming influence in my life as far as writers go, was definitely the great Russians — Dostoevsky, Chekhov — and from a later age, the American novelist, William Styron.

As a Parsi, did you think that you belonged and what did you think of your identity?

I like Parsis and find them good-natured and pleasant in a very general sense. But I never identified myself with their lot in toto. My school was cosmopolitan and we had a lot of Parsis besides students from other communities. But I was always slightly embarrassed by the clannish claims that Parsi students made. I shared no in-group feeling with them. My wife (and long-time girlfriend whom I met at college) is an East Indian Christian, Jill. So technically, from the ultra-orthodox Parsi point of view, I am something of a maverick and outcast.

Cyrus with wife Jill and son Rushad

Now, 45 years since you wrote Doongaji House, as you revisit the Bombay you were so much a part of, how do you see the city’s transformation?

Basically, I see it as inevitable — but even more so, as undesirable.

Cyrus Mistry is managing his multiple sclerosis much more effectively in the cooler, verdant, less crowded environs of Kodaikanal. He says he has no regular routine that orders his writing life. He is very much a family person and spends a fair amount of time in the kitchen with his wife. When he is working, he writes for only about two or three hours in the morning. He has a digital piano in his study, whose keys he feels the need to caress now and then both for cerebral relief and as fresh impetus for his next book.

Your fascinating novel Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer explores the complex and closed lives of Parsi corpse bearers. How did you conceptualise this plot? You mention that it was sparked by a real-life story.

More than 10 years before I wrote this novel, I was asked to do a treatment paper on the corpse bearers by an Irani documentary producer. He was hoping to sell the idea to Channel 4 of British television. The channel didn’t buy the idea, so the film was never made. But during my research for the docu, I met one corpse-bearer (and many others too) who was a lower middle-class Parsi, not belonging to the corpse-bearing caste of khandhias. He told me his own story of how he fell in love with a corpse-bearer’s daughter, and for the sake of love, declassed himself as it were, voluntarily adopting the lowly profession. In my novel, I heighten the conflict of declassing by making the boy who falls in love with the corpse-bearer’s daughter the son of a head priest of an agiari.

This book must have been a tough book to write. The abjectness, horror and utter despair of death must have been constantly present. How did you get through this and yet shine some glimmer of light?

Of course, you’re absolutely right. With consciously planning it to be such, my greatest approbation for the novel was when a friend read it and said that he had avoided reading the novel for a while because of the association with death in the title, but when he did read it he found it such a positive and life-affirming novel. That was a real compliment.

Are you a writer who researches the subject before you write the story?

In this case, I didn’t need to research more than I already had for the documentary treatment paper. During that research I remember even speaking to priests to find out the ecumenical position on death, after-life, etc. But, in general, I don’t at all believe in research for writing a work of fiction. One has to believe in the power of one’s imagination and allow it to lead one into all the warren holes of the mind. I believe it’s only when the imagination has free rein that structure and creative unity and breathtaking surprises can naturally evolve — not by following a pre-decided scheme of plot development.

In the very rare and fragile collection of stories about the Parsi community Cyrus Mistry’s fiction and drama represent the cultural and community history of a fast disappearing community worldwide. In the academy, Cyrus Mistry’s writings are crucial. They will gain much value as ethnographic records and be referred to by cultural history scholars as historical. archives. He spearheads the small band of writers today like novelists Rohinton Mistry, Anush Irani, Thirty Umrigar who are doing the precious work of cultural archivists.

Doongaji House was a roaring success. Could you tell us how this took on a life of its own?

I wrote Doongaji House, my first play, when I was just 21. I wrote it specifically as an entry for Theatre Group’s Playwriting Contest. It won first prize. This was 1978. One of the conditions of the contest was that the prize-winning plays would be produced by Theatre Group. After years of dithering and procrastinating, the group’s office-bearers told me that they had decided not to produce the play because they felt it was not “commercially viable”. But 13 years after it was written, Toni Patel of Stage Two produced and directed the play. It was a great success, and the play saw many shows and various productions, especially an excellent one in Marathi translation (by Chetan Dataar), which travelled to various cities and towns in India.

It is the captivating way you texture your tellings with minutiae that makes you stand out among contemporary and postcolonial writers. Have you always been a serious observer of human beings, or did you train yourself to pay attention to these details that make for rich and nuanced characters?

Thank you for your sensitive reading of my work. I have no idea if I can consciously say that I am an observer of human nature. Some writers do make themselves attentive to such details, but I don’t think that I actually train myself in that. All I know is that I should try to tell a story as evocatively as possible. And writing fiction is such a demanding activity, doing it as best as one can is its own reward.

With two gifted brothers in the family attaining stardom as celebrated writers in their own right, who inspired whom to take up the pen and tell these compelling stories of the Parsi community?

Incidentally, Rohinton Mistry is my elder brother who migrated to Canada some 40-odd years ago. I am proud to say, and Rohinton would willingly acknowledge this too, that he was inspired to start writing his fiction about Parsis only after he read my first play, Doongaji House, and my first few short stories which were published in Indian magazines.

JULIE BANERJEE MEHTA

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Lifeand co-author of the bestselling biographyStrongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. Shehas a PhD in English and South Asian Studies fromthe University of Toronto, where she taught WorldLiterature and Postcolonial Literature for manyyears. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Master’s English at Loreto College.