Book: BEING HINDU, BEING INDIAN: LALA LAJPAT RAI’S IDEAS OF NATIONHOOD

Author: Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav

Published by: Viking

Price: Rs 1,299

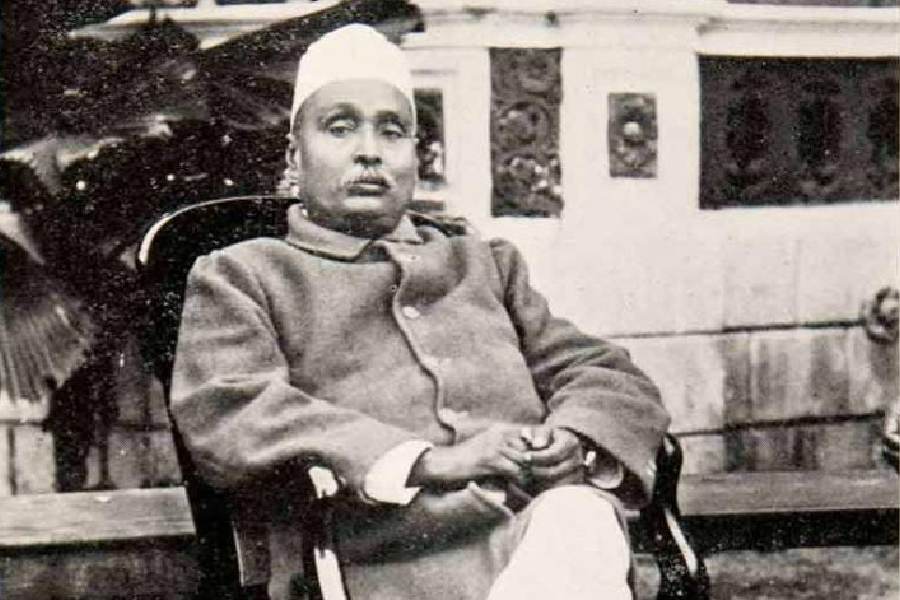

Lala Lajpat Rai (1865-1928), the iconic Hindu leader with an eclectic vision of nationalism, hardly needs any introduction. However, in our present times of hyper-nationalism where an ascendent Hindutva populist discourse seeks to appropriate the past through its monocultural interpretations, a debate is needed. Was Rai a Savarkarite or a secularist? Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav’s book intervenes by offering an exhaustive account of Rai’s nationalist thoughts.

Contesting different strands of historiography and appraisals that cast Rai as a forerunner of or a contributor to Hindutva ideology, Bhargav contends that his Hindu pluralistic nationalism was different from Savarkar’s muscular Hindutva. Arguing for a need to “explore the internal complexity within ‘Hindu nationalism’”, the author chronologically traces Rai’s “multiple ideas of nationhood” — ideas that are evident in Rai’s early formulations of Hindu cultural nationalism — in his diversity-oriented wartime nationalism, in his views on Hindu-Muslim unity, and in his belief in ‘secular’ Indian nationalism as a Mahasabha leader.

While agreeing that there were commonalities and overlaps between Rai and Savarkar, regarding pan-Islamic anxieties and Hindu militancy, the author asserts that Rai was never swayed by Savarkar’s Hindutva propagation of Hindu culture as the sole definition of India and that he favoured the granting of proportionate representation to Muslim minorities. Further, the book avers that Rai’s belief in Hindu militancy was strategic and not ideological because while he championed militant Hindu politics, he envisioned a “radically ‘secular’ state and politics — free of all markers of religion.”

Rai’s seemingly contradictory nationalism — both as a Hindu leader and as a secular patriot — afforded him the flexibility to espouse the Hindu claim that the Swarajists resist and simultaneously advocate the importance of Muslim ‘proportionate’ representation which the Hindu hardliners rejected. In the author’s view, Rai’s conception of nationhood anticipates the modern view of secularism premised upon a “majority-minority framework”, a framework which prevents secularism from being a “mere cover for Hindu majoritarianism.” The relevance of Bhargav’s book lies in its appreciation of Rai as a stalwart of modern secularism.

However, since the book aims to offer the “first systematic intellectual study of Lala Lajpat Rai’s nationalist thought”, its ability to uncover outside of what is known and its stylistic skills deserve reviewing. Hence, in the Introduction, where the author maps existing scholarship, the omission of K.L. Tuteja’s study of colonial Punjab and of Lajpat Rai is surprising because it foreshadows many of the arguments in Bhargav’s book; Tuteja’s use of the term, “nationalist-communitarian perspective”, comes remarkably close to Bhargav’s analysis of Rai’s secularism.

Undoubtedly, an omission need not be significant since the author rightly notes that “history is an interconnected, collective enterprise”, but there are parts in the book, where, because of a willing looseness in writing, meaning-making suffers. For instance, it remains unclear why Bhargav chooses the word, “temporary”, to analyse Rai’s involvement with the Mahasabha. Phrases such as “the Mahasabha was almost imagined as a temporary organization”, or that the Mahasabha was a “temporary remedy”, or that Rai required “temporary ‘communal’ politics” are mystifying since there’s nothing to suggest that Rai’s engagement with the Mahasabha was time-driven as the word ‘temporary’ suggests.

Likewise, the inferences are confusing in places. For instance, while analysing Rai’s appeal to Congressmen to participate in the Mahasabha, the author opines that Rai’s appeal was meant “to prevent it [the Mahasabha] from mistakenly becoming ‘aggressive’ towards other communities.” Since this is a “literal” account of a part of a sentence from a well-known public speech given in 1925, the possibility of Rai using the idea of Hindu ‘aggression’ rhetorically cannot be ruled out. For, if the Mahasabha could become ‘mistakenly’ communal, why would Rai assert, just before the citation, that “the Hindu community as a community is incapable of adopting an aggressive policy against any other community”? Further, why would he, in the same breath, ask Congressmen to “join the Hindu Sabha in large numbers and in such large numbers as would really strengthen it and vivify it”? (Collected Works, Vol 11, p 212).

Notwithstanding stylistic problems, Being Hindu reminds readers that Hindu nationalism was not a monolith, and that leaders like Lajpat Rai did offer an enlightened understanding of religious diversity within a nationalist framework. While lessons from the past are important, one cannot overlook the fact that, unlike our present times, Rai’s vision of accommodation arose out of the anti-colonial history. Secularising and democratising society today demand equality and justice for all citizens. How do we ensure these in the context of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act?