KNIFE: MEDITATIONS AFTER AN ATTEMPTED MURDER

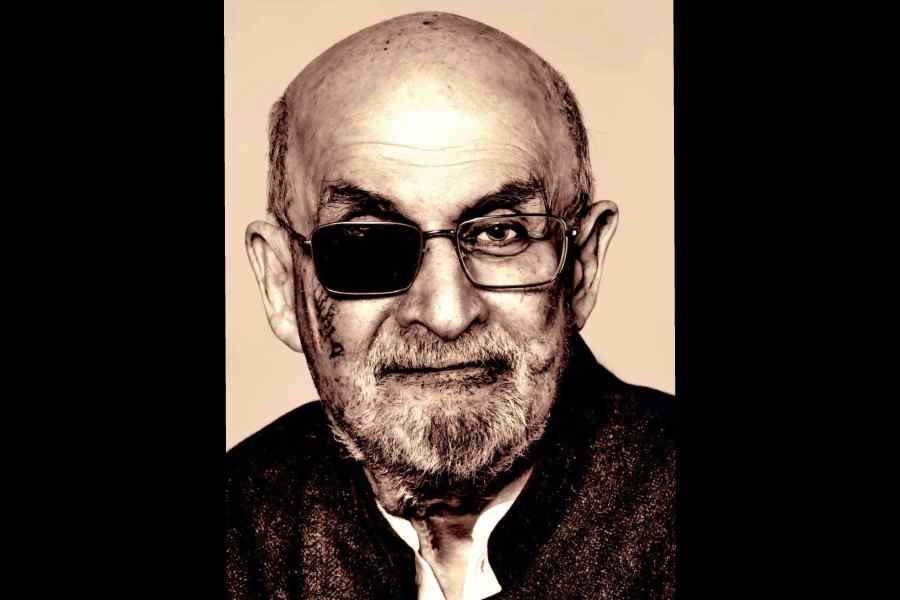

By Salman Rushdie

Hamish Hamilton, Rs 699

In one of the richly reflective passages in Knife, Salman Rushdie ruminates on Coleridge’s analysis of Iago’s capacity to inflict violence sans rationale. This reference to the villain in Othello is apt: for the readers of Knife are likely to be made aware of their inner battles with their own Iagos. On the one hand, there is our baser, aberrant desire to savour the details of the violence that was perpetrated on the writer on a beautiful morning at the Chautauqua Institution, the site of the murderous attack on Rushdie. And Rushdie, never one to shy away from interrogating incidents that mirror our times, including a near-fatal attack on him, indulges our morbid curiosity, beginning with an unforgettable, cinematic description of the moment of his recognition of possible oblivion: “I remember raising a hand to acknowledge the applause. Then, in the corner of my right eye — the last thing my right eye would ever see — I saw the man in black running toward me down the right-hand side of the seating area. Black clothes, black face mask. He was coming in hard and low: a squat missile… I was transfixed.” [Reviewer’s italics in all quotes]. The description of the aftermath of the drawing of his blood — copious amounts of it — his horrific injuries, and an inordinately slow and painful recovery would satisfy even the most prurient of souls.

But reading Knife only for its unflinching, graphic portrayal of a grievous attack on a person would be a travesty. This is because Knife’s hypnotic pull — the subtitle holds the clue — lies in a fecund mind’s reflections not only on a savage assault and its consequential losses — of an eye, bodily mobility, privacy, freedom — but also on the deeper catalysts that ignited the brutality. These peeks into what Rushdie writes is the “free-associative” working of his mind are the truest rewards for the reader. For starters, there is Rushdie’s masterful employment of foreshadowing as a premonitory narrative technique. One of his musings, “[o]n that last innocent night”, the night before the day of the attack, a day that will change his life, once again, since the fatwa, is on the scene of a moon landing from a classic, early-twentieth-century film, Le Voyage dans la Lune, in which the spaceship wounds the moon’s right eye. There are also his thoughts on the randomness of violence, its dark power to dissolve reality, trapping its victim(s) in a realm of incomprehensibility and inaction; on the tools of violence — “… a knife is a tool, and acquires meaning from the use we make of it. It is morally neutral. It is the misuse of knives that is immoral”; on the blurring of borders between the Self and the Creative Self, between real and unreal — “I don’t believe in miracles, but my survival is miraculous. Okay, then. So be it. The reality of my books — oh, call it magic realism if you must — is now the actual reality in which I am living. Maybe my books had been building that bridge for decades, and now the miraculous could cross it. The magic had become realism. Maybe my books saved my life.”

And, as always, there is the signature Rushdian black — condescending? — humour: on being assured by a doctor that he was a “champion” when it comes to draining fluids from lungs, Rushdie “thought (but did not say), I didn’t know there was a championship?... A Super Bowl of fluid draining? Who would perform the halftime show? Muddy Waters? Aqua?...”

Comparisons between Knife and Joseph Anton, Rushdie’s memoir of 2012, are inevitable but also unnecessary. This is because Knife, brutal and tender, does not chronicle a life, but is a meditation on the attempt to take a life — Rushdie’s own; it is also Rushdie’s way of “taking ownership of” an act of random violence not merely to record it for posterity but also, courageously and with undiminished luminosity, leach it of the poison. Rushdie’s imaginary conversation with his assailant — giving away the details would be a disservice — is a testament to an individual’s and, hopefully, humanity’s, ability not to be seduced by — resist — hatred’s enchantment.

The most telling and endearing certificate of Rushdie’s moral resilience, of his unvanquished core, comes from a dying Martin Amis who, in a brief but vigorous email to the writer, wrote the following words: “When we recently saw each other… since the atrocity… I expected you to be altered, diminished in some way. Not a bit of it; you were intact and entire. And I thought with amazement, He’s EQUAL to it.”