Biden vacillates between embracing the image of a kindly grandfather and bristling at it. The late-night host Stephen Colbert once referred to him on the air as a “nice old man”. It was 2015, and Biden called him the next day, Colbert told me. “He goes, ‘Listen, buddy, you call me a nice old man one more time and I will personally come down there and kick your ass.’ I laughed, and he laughed. I said, ‘Don’t worry. I won’t call you a nice old man, because clearly you’re not that nice.’”

In truth, Biden’s effusiveness has always accompanied a prickly side. Among staff, he is known for giving support to talented people without connections, and calling his employees’ mothers as a surprise, but he can also be curt and demanding, leaving the menial work of fund-raising to others. He sometimes lavishes more gratitude on strangers who want selfies than on aides who have spent years keeping him in office. Jeff Connaughton, a disenchanted former aide, once called Biden an “egomaniacal autocrat”. But Connaughton, who became a lobbyist, also admired Biden’s contempt for the corrupting glad-handing of Washington. “Biden never lifted a finger for me or for one of my clients,” he wrote, in his book, The Payoff. “Unlike most of Congress, he hardly ever schmoozed with the Permanent Class. He did the best he could to stay as far away from it as possible.”

For all his longevity in Washington, Biden has never quite belonged to the technocratic elite. To the dominant Democrats — the Clinton and Obama circles — he was too mawkish with the Amtrak Joe routine, too transparent in his ambition. Biden is the first Democratic nominee without an Ivy League degree since Walter Mondale, in 1984. In a milieu of Rhodes Scholars and former professors, he is thin-skinned about condescension, real and imagined. He was barely in the West Wing before The Onion declared, in a headline, “Shirtless Biden Washes Trans Am in White House Driveway”, establishing a theme — “Amtrak Joe,” the hell-raiser at the end of the bar — that was so enduring that it obscured the fact that he is a lifelong teetotaler. (Too many alcoholics in his family, he said. He grew up sharing a room with his mother’s brother, and recalled of the experience, “Even as kids, we noticed Uncle Boo-Boo drank a bit heavily.”) Biden’s insecurities fed a certain openness and vulnerability. Even after decades in national office, he talked to any one in reach, partly because he was trawling for what others knew and he did not. A senior Obama administration official, who periodically briefed Biden, recalled, “He would talk for 90 per cent of the conversation. And yet he always picked something up. At the end, we’d get up and walk out, and he’d clap me on the back: ‘Great talk.’ And I’d be a bit dazed.” The official added, “So the question is which Joe Biden governs: The one that is sincerely open and searching for the perspectives that will help him be more effective? Or the Joe Biden that will talk at you because he thinks he has enough words and expertise to muscle through any situation?”

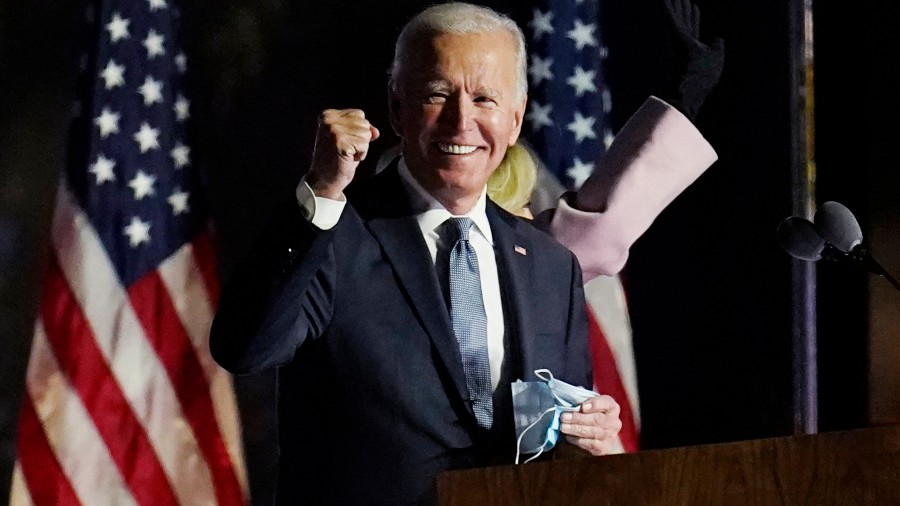

THE BLUES: Joe Biden and wife Jill; (right) Biden with Kamala Harris Shutterstock

For years, Biden has contended with a harrowing tendency to put his foot in his mouth. Talking about American soldiers who were hounded by debt collectors during deployments, he once condemned the “Shylocks who took advantage of these women and men”. In footage of the speech, in the fall of 2014, his gaze swept across the audience, and, judging from the flicker that passed across his face, one senses that he glimpsed a familiar hint that he may have devoured another heaping portion of foot. “Action is eloquence,” Shakespeare observed, in the early 1600s, just a few years after he wrote The Merchant of Venice, the play that established a Shylock as a reliable slur. After Biden’s comment, the Anti-Defamation League’s national director, Abraham Foxman, said it remained “an offensive characterisation to this day”. Because Biden is a longtime supporter of the Jewish community, Foxman put the moment in context: “When someone as friendly to the Jewish community, and as open and tolerant an individual as is Vice-President Joe Biden, uses the term ‘Shylocked’ to describe unscrupulous money lenders dealing with service men and women, we see once again how deeply embedded this stereotype about Jews is in society.” (Biden quickly apologised for “a poor choice of words”.)

A few weeks later, he was in trouble again — but, this time, it was for saying something true. At Harvard’s Kennedy School, Biden finished his formal remarks and went free range when a student asked whether the US should have intervened earlier in the Syrian civil war. “Our allies in the region were our largest problem in Syria,” Biden said, a characterisation that allies do not generally enjoy. He listed the Turks, the Saudis, and the Emiratis, and said, “They poured hundreds of millions of dollars and tens of tonnes of weapons into anyone who would fight against Assad — except that the people who were being supplied were Al Nusra, and Al Qaeda,” a stream of support that helped foster a resurgence in Sunni radicalism. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan demanded an apology and called his relationship with Biden “history”. (Biden apologised to Erdogan two days later.)

His tendency to say out loud what others in Washington said in private caused him trouble at work. In describing the role of America’s regional allies in Syria, Biden was largely correct. The US had publicly called on the Turks to seal their border to jihadists en route to Syria, and experts did not question that money from Gulf countries had ended up in the hands of militant extremists there. Andrew J. Tabler, of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, told The New York Times that “there are factual mistakes, and then there are political mistakes” — and Biden’s was the latter.

Biden’s misadventures, which tended to strike when he ventured “off prompter”, in his staff’s anxious phrase, was part of the reason that political wags so often underestimated his potential. Many Americans outside of Washington greeted those moments with a shrug. In fact, Biden’s off-the-cuff moments at Harvard distracted from what was, in retrospect, a prescient appraisal of foreign affairs, in which he drew connections between crises — Isis, Ukraine, Ebola — and growing territorial tensions with authoritarian powers. Biden called for strengthening Nato, helping “small nations resist the blackmail and coercion of larger powers using new asymmetric weapons” (a reference to Russia and China). He described a new era defined by an “incredible diffusion of power within states and among states that has led to greater instability” requiring “a global response involving more players, more diverse players than ever before”.

Excerpted from Joe Biden: American Dreamer by Evan Osnos with permission from Bloomsbury Publishing