SAFDAR HASHMI: TOWARDS THEATRE FOR A DEMOCRACY

By Anjum Katyal

Orient BlackSwan, Rs 900

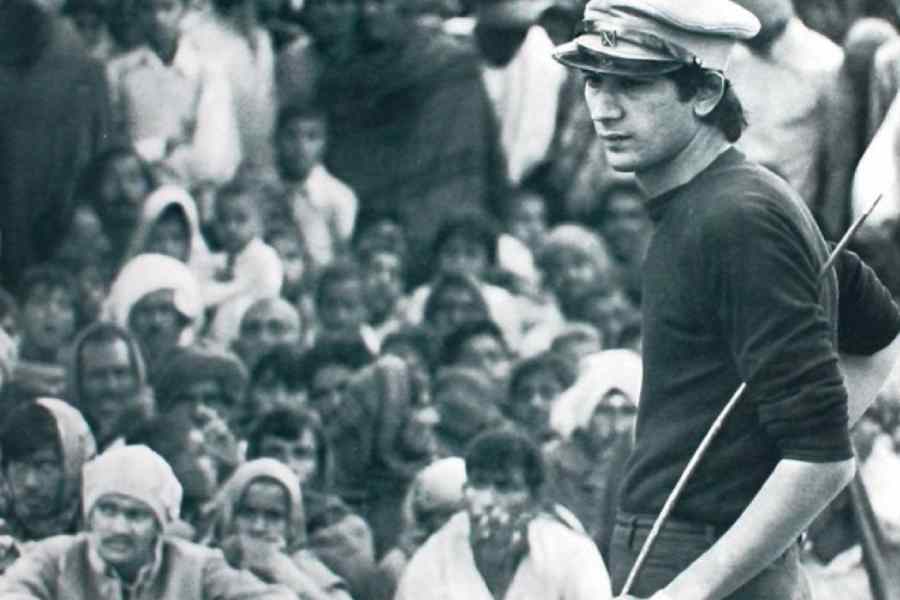

Safdar Hashmi (1954-1989) was a well-known cultural icon about whom much has already been written. His untimely death following a brutal attack while performing a street play in Ghaziabad had shaken the national conscience. The Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust has played a key role in keeping Hashmi’s legacy alive. Anyone with even a faint acquaintance with India’s recent cultural history would have surely heard of Safdar Hashmi and his multi-faceted talent as an actor, playwright, activist, poet and organiser. His founding of Jana Natya Manch (Janam) in 1973 is seen as a watershed moment in the development and growth of street theatre in India. Indeed, his creativity was not confined to Janam. He wrote scripts and directed short films for television. He wrote on culture and theatre for national newspapers. More importantly, he was a key voice of the Committee for Communal Harmony, which was formed to counter the onslaught of communalism and fundamentalism. As an organiser, he envisaged a national, democratic, cultural movement to privilege and showcase the everyday struggles and the experiences of the masses.

In this short biography, Anjum Katyal delineates the larger democratic vision that informed Safdar Hashmi’s cultural activism. She attempts to situate his work in the ethos of the times that shaped his political sensibilities. The author takes pains to expand on Hashmi’s broad humanism and inclusiveness despite the fact of his being a member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) from 1976 till his premature death by murder. She offers us peeks into Hashmi’s illustrious, though short, career: from his early life and formative influences to his forays into theatre in Delhi in the 1970s to the gradual mastery of his own distinctive language of street theatre in the 1980s. His street theatre would intend to initiate a debate amongst its audience and also engage with it on the political questions of the day.

For Katyal, Hashmi’s work is of a piece within the larger history of Indian political theatre. In her reading, his street theatre was, in effect, an evolving embodiment of a vision and practice of democratic theatre and was meant to partner with “progressive, democratic, and secular” segments of society in order to contribute to a robust democracy. Moreover, to the extent street theatre brought in opposition, protest, critique and dissent in its renditions, it invariably presented an alternative point of view to the dominant mainstream narrative. This very questioning of the mainstream discourse also opened up spaces for the inclusion of issues and subjects that would otherwise be marginalised or silenced. According to Katyal, such interventions were characteristic of the works of Hashmi and Janam. That is why she terms them, as the subtitle suggests, “towards theatre for a democracy” for they enriched the health of our democratic culture.

The author’s ultimate position is that Hashmi’s work was democratic in the way he conceived street theatre and presented it. He explicitly conceptualised street theatre as an ally of popular democratic and mass movements towards which it would inform, educate and help mobilise the common man. Yet, Katyal’s assertion that “the true significance of Safdar’s work and his lasting identity as a national figure, is because his central concern was helping build, and strengthen democratic process and practice much beyond the Party line” is more a statement of unqualified admiration than an evidence-based, reasoned argument. In fact, she treads on too familiar a ground in terms of her sources and references. All of them are already convinced of Hashmi’s greatness and are avowed upholders of his legacy. Appreciably enough, the biography contains English translations of three of Janam’s most popular plays: Machine, Hatyare and Aurat.