COURTING INDIA: ENGLAND, MUGHAL INDIA AND THE ORIGINS OF EMPIRE By Nandini Das, Bloomsbury, ₹699

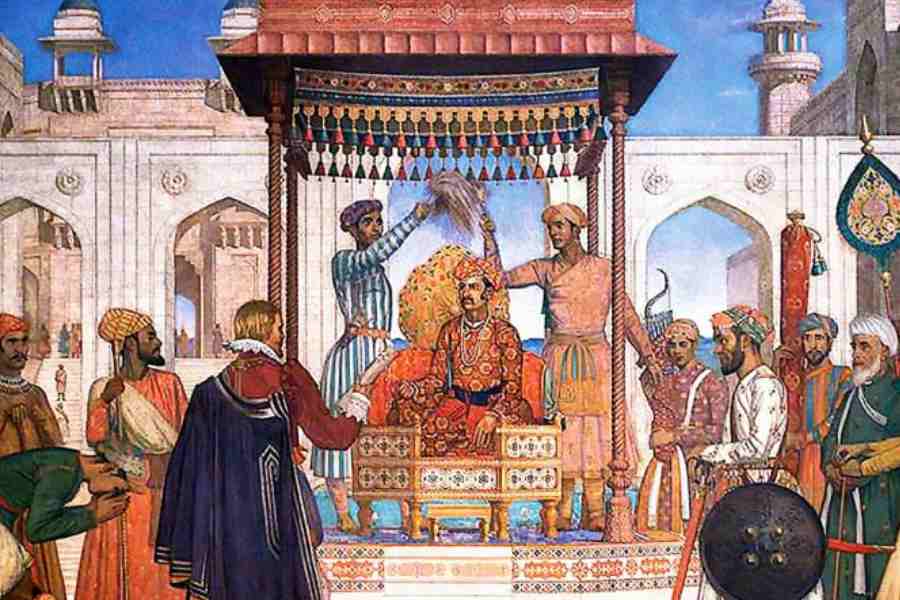

Courting India positions itself somewhat unassumingly as the history of the first English embassy to India in 1616 or, more specifically, of Sir Thomas Roe’s visit to the court of the Mughal emperor, Jahangir. What it offers, however, is a fascinating retelling of that story with compelling scholarship and sparkling prose.

Roe’s embassy was entrusted with the task of acquiring a series of trade permits and protection from the Mughal emperor that would allow the Company to set up permanent trading links with the subcontinent. He resided in Agra for three years and left behind a remarkable journal and a cache of letters. Roe’s journal entries of the first year of his stay in India in 1616 form both the point of entry and the critical site of engagement from which the author, Nandini Das, effects the subtle displacement of the story of the embassy, from the commanding narratives of the British Empire to the more nuanced micro-histories of early modern travel, transculturality and identity.

Das places Roe’s testimony alongside multiple other accounts, some contemporary and some from the more recent past. She digs out every accessible record in English, Dutch, Latin, Spanish and Portuguese among European languages as well as several Persian sources. Apart from these that surround the textual world of 16th and 17th centuries’ travel and cultural encounters in a broad sense, Das mines the Company’s monumental archives to retrieve manuscript repositories of the times, particularly those that dealt with the Asia trade. The use of multiple lenses on a single recorded event is a recurring ploy in the book that adds the critical lens on Roe’s account for what it observes, records, comments, ignores and chooses to gloss over.

Yet, as much as Roe’s account is placed within the larger genre of European travel writing, chronicling, memorialising, it is also placed within the broader cultural and literary world of 17th-century England, including popular theatre that reflected the political and social crises of early Stuart rule. Roe’s friend, Ben Jonson, for instance, wrote several plays that spoke of rifts between the monarch and Parliament and of the fractious voices within Parliament itself. Other, more cynical, writers of chapbooks commented on the extravagance of the James’s Court in the face of the dire state of his finances and wrote pruriently of the king’s sexual proclivities.

But despite the disquieting accounts of strife between King and Commons that circulated in English public life, a growing sense of national pride and an unyielding faith in the glorious destiny of English Protestantism are what held king, Parliament and trading companies in a kind of uneasy alliance. In other words, trade, travel and enterprise captured the public imagination at a time when England’s anxiety about its place in global trading networks acquired urgency. This was occasioned by an export crisis in the wool trade brought on by England’s fraught relationship with Catholic Europe following Queen Elizabeth’s excommunication by Pope Pius V in 1570 and, almost simultaneously, by a surge in the domestic appetite for a new kind of consumerism in foreign luxuries. English trading companies already operational in the Atlantic trade knew they were late to the Asia trade and that much work was needed to reclaim* lost ground. Yet, Roe’s embassy to the Mughal court of Jahangir was an evidently failed attempt to secure trading privileges for the East India Company, and it did not at that time indicate any great prospects for a British imperial project in the offing. Why then study a failed embassy?

This is where Das succeeds in pressing the significance of the Roe embassy by pointing to the limits of rehearsed platitudes of Empire. Roe’s presence in received histories of Empire, she argues, is often a routine opening vignette that tells us little about what England’s first embassy may have signified to the court, to the trading companies, to Parliament and to the people at large. Roe’s journal encourages her to ask what could have been the role of an embassy or an ambassador in the structures of early modern Statecraft. How was an ambassador positioned between the court and a trading company? What were the rules of engagement with non-Western courts? How were these conceived and formalised? What did India mean to England in the 16th and 17th centuries? Or, more importantly, what did England mean to the Mughals? How did the Mughals, then at the peak of their wealth and power, discern foreign visitations to their courts? What were the considerations — political, economic and cultural — that informed the grant of trading privileges? Why or how did the Dutch or Portuguese succeed? Why did Roe fail?

Roe’s journal bears answers to all these questions from his personal understanding of the embassy, the emperor, and his own sense of self. He emerges from this retelling as a young, Oxford-educated courtier and adventurer who for all his inherited cultural capital remained deeply baffled by not only the enigmatic emperor, Jahangir, but also by a court and a cosmology that were distinctly alien and at times inimical to his Anglican Protestant sensibilities. There is no better example in the book than in the numerous references to Roe’s anxious obsession with the Mughal ritual of ‘gifting’ to show how doggedly he struggled to convey a sense of his self-worth to himself and to the emperor.

This is a book to be read not only for its new and brilliant intervention in the annals of Empire but for the sheer magic it conjures in telling the poignant tale of a traveller in a foreign land teetering on the brink of losing himself in a cultural maelstrom but surviving to tell his story of fortitude and redemption.