Book: SOVEREIGNS OF THE SEA: OMANI AMBITION IN THE AGE OF EMPIRE

Author: Seema Alavi

Published by: Allen Lane

Price: Rs 999

Sovereigns of the Sea looks at the life histories of four Omani rulers of the Al Busaidi family to retell the history of the Indian Ocean in the long nineteenth century, largely in terms of its emerging political culture that the Omani sultans scripted in conversation with their global counterparts. It argues that a micro-historical approach to the policies of the sultans helps counter conventional narratives of Omani rulers being decadent, treacherous and inept and to consider an alternative narrative of agency on the part of non-European actors in the Indian Ocean. The complex ways in which the Omani sultans crafted their global, maritime ambitions and balanced them with immediate local and tribal compulsions form the staple of the book and are eloquently told. What is not so clearly delineated is the distinctiveness and the originality of the Indian Ocean political culture to which the Omanis contributed. It would seem that like merchants and mariners, the articulation of politics was ad hoc and contingent, whose efficacy was determined by the gaps in the imperial apparatus of power. So if we flip the argument and see the actions of the Omani sultans as a consequence of the lacunae in the system of controls, would the case for agency be as persuasive?

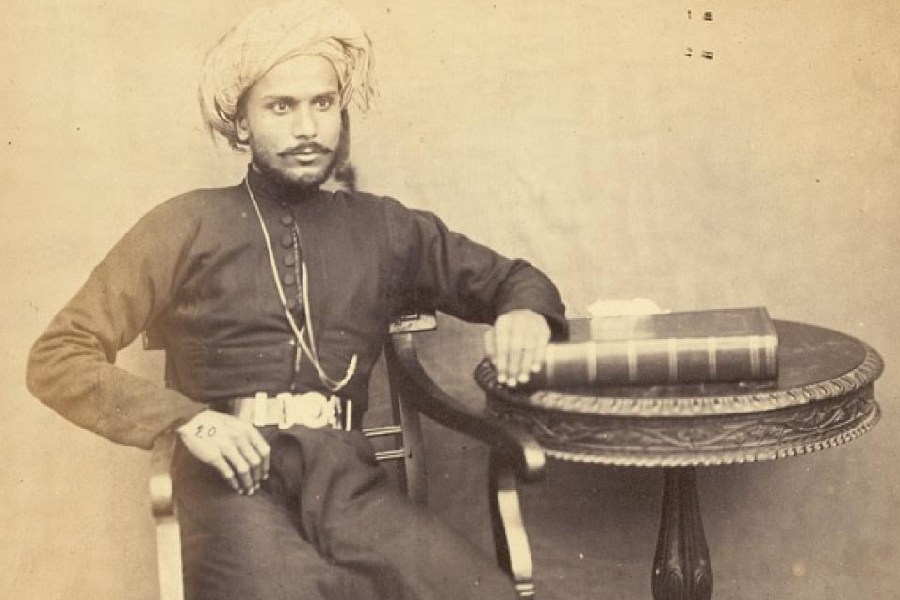

Alavi comes up with a solid, detailed and empirically rich history of the political strategies of four Omani rulers, all of whom were determined to safeguard their maritime ambitions which they directed from Zanzibar. This brought them face to face with European powers engaged with the slave trade and forced them to take a stand when its regulation and abolition were being discussed and debated. Sayyid Sa’id (1791-1856) was the first to articulate an explicitly maritime policy, choosing, for instance, to rule from Muscat and set up his base in Zanzibar to maximise his proceeds from the slave trade. This was not a case of a local ruler’s vanity; Alavi argues that he envisaged for himself a role in the new world system and even oversaw a revolutionary transformation in his domain. Among the elements of revolutionary zeal, mention is made of a cross-cultural household with a strategic effort to balance the politics around slavery and reformist Islam to further his own interest. According to the author, these policies helped foster a cosmopolitan modernity in the Sultanate of Oman. It is, however, not very clear what this cosmopolitan modernity looked like and whether strategic manipulation of imperial rivalries around the slave trade and of tribal compulsions in the interior could legitimately stand as a proxy for a fundamental transformation of political culture.

In its organisation, the book looks at the reigns of four sultans and their politics. Deeply embedded in archival research (mostly British colonial documentation), the narrative is replete with details that could make for tedious reading. But it is to the credit of the author that she prefaces every chapter with a clear argument and helps the reader along with a racy style that captures the dizzy world of intrigue and diplomacy in which the rulers were involved. Also remarkable is how the personalities of the sultans are brought out; we have, for instance, the example of Sayyid Sa’id who blazed the trail in maritime State building, built a fleet, and made Muscat the new commercial node in the history of the western Indian Ocean. His ability to leverage imperial rivalries — what Alavi calls “forum shopping” — served him well as he made a mark as a maritime player. Whether one would call him a global competitor to the British in the region is not so convincing; for one, when he tried briefly to compete with British traders in the China traffic, he was warded off. It is also important to keep in mind that the western Indian Ocean, which was the playground of the sultans, was a relatively freer space for manoeuvre and manipulation that traders and merchants alike took advantage of.

Sa’id’s successor, Sayyid Majid (1834-70), found himself in the thick of the slave trade controversy. His own power was predicated on the profits of the slave trade and the plantation economies dependent on slave labour, and it was to his credit that he managed to bypass British control of the slave traffic and make his presence visible in the imperial world. Where this visibility counted was in the documenting of legal subjects who were allowed to register as protected subjects of the ruler and, with it, the right to possess slaves. The registration protocol sharpened Majid’s sovereign status and is an important episode in the intersecting histories of law and sovereignty in the western Indian Ocean, which emerged as an Anglo-Arab lake. The sultans who came in succession were as deeply entangled in the politics of global diplomacy and trade. Not all of them were as successful but failures did not deter them from maintaining connections with a wider world.

Alavi’s work is certainly an important addition to the scholarship on the Indian Ocean and is a successful experiment in writing a new kind of political and global history. Its style is unique in that it focuses entirely on politics and political manipulations of the sultans and the Omani elite. Even though this stands in the way of revisiting older conversations around slavery in the Indian Ocean or, indeed, on Islam and its networks, it powerfully reminds us of the extraordinary circulation of ideas in the region that made maritime states such as Oman so important.