Book: In Search Of The Divine: Living Histories Of Sufism In India

Author: Rana Safvi

Publisher: Hachette

Price: ₹599

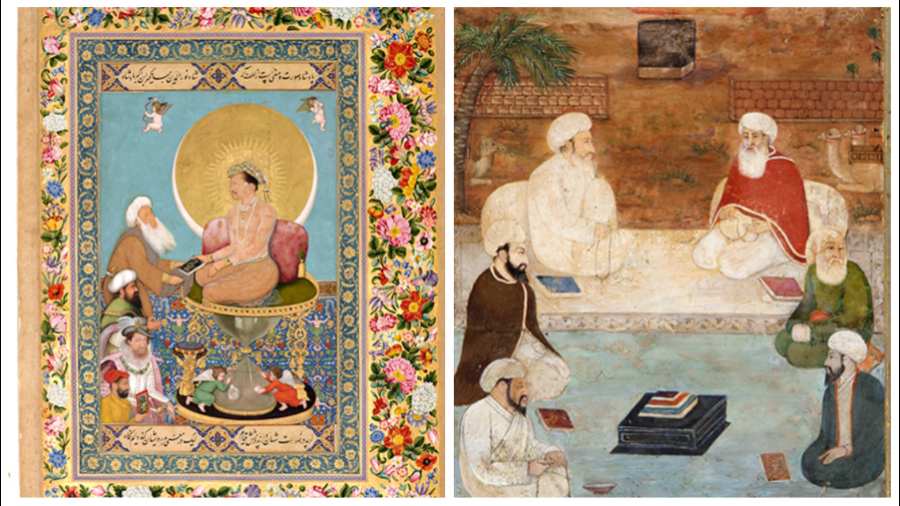

Rana Safvi’s book is a lucid, readable and detailed introduction to the various traditions of Sufism or tasawwuf in India. She describes the basic tenets of Sufism, recapitulates the history of early Islam, beginning with Muhammad and ending with the battle of Karbala, and stresses the value of the household of the Prophet — the Ahl al-Bait — to Sufism. Safvi then narrates the spread of Sufism in the world and into South Asia. For India, she provides suitable commentary on the four major traditions of Sufism — the Chishtis, the Suhrawardis, the Qadriyas, and the Naqshbandis — as well as the Qalandars and other minor silsilahs/traditions. The final section of the book presents us with the dargah or the shrine as an important locus of Sufism in India in its theoretic, personal, as well as its different practical manifestations through narratives of the popular dargahs in various parts of India.

Safvi makes two major claims. The first is to set up Sufism squarely within the realm of Islam unlike Western and other portrayals that see it as a secular spirituality that exists despite Islam rather than because of it. Consider Rumi as one such example who has been rendered almost fully secular despite actually being the strongest of believers. Safvi achieves her aim through her close historicising of the different facets of Sufism and by making apparent Sufi concepts and stages which are all Islamic: such as akhlaq (pious morality, not secular ethics), iman (faith), ihsan (perfect devotion), tariqah (“mystical path” according to Safvi, which I would more simply render as ‘method’), haqiqah (truth), marifah (gnosis), ikhlas (sincerity), zikr (remembrance), ishq-ehaqiqi (love for the divine), wahdat-ul-wajud (the unity of being — of God and the universe) and so on.

Her second claim is to chart out her story of Sufism in India as a practising Muslim since her childhood and as a Sufi initiate since the last decade. This gives the book great immediacy for the reader and prevents the detailed history from becoming dull. Her personal voice brings alive various dimensions of a complex subject as she takes the reader along on her journey.

It is this personal dimension that also renders her opinions a bit narrow. As a minority Muslim among the Muslims of India, her emphasis on various Shia aspects of Islam is both interesting for the singular facets of the internal diversity of Islam it opens up, but her preponderance also makes her narrative slip. Consider the following quote Safvi uses of Haydar Amuli although she admits to not having an authentic source for it: “Shi’ism is the external teachings of the imams, while Sufism is the internal teachings of the imams.” This makes it appear as if Sufism and Shiism are two sides of the same coin, while not alerting the reader explicitly to the fact that all four dominant Sufi orders of India are primarily Sunni. One also misses a detailed and clear explanation of a most important Sufi concept that is universally recognised and which sought to unite the Shariat and Sufism — wahdat-ul-shahud, the unity of witness or appearance (of God) given by an Indian Sufi, Ahmad Sirhindi.

Nonetheless, Safvis’s work is a long labour of love and the longest section on Indian shrines really shines with her deep investment in exploring the Sufi realm of love in and with India. The book would prove to be a most useful guide to those disciples interested in this quest for the divine in Hindostan through tasawwuf and may even work as a mystical travelogue.