Book: There Are Places In The World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness

Author: Carlo Rovelli

Publisher: Allen Lane

Price: Rs. 999

“To hear a cultivated person of today joking almost boastfully that they are completely ignorant about science is as depressing as hearing a scientist bragging that they have never read a poem,” writes the Italian physicist, Carlo Rovelli, in one of his newspaper columns, which have been collected in this volume.

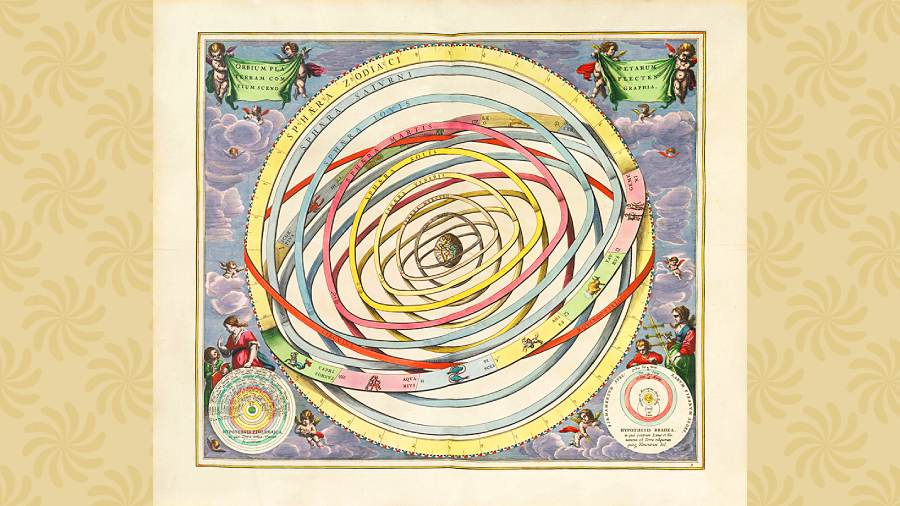

Before the sciences became pompous and downed the portcullis on the arts, thought was borderless. Rovelli reminds us that Dante was scientifically literate, and the universe he describes in the Divine Comedy is a three-sphere, a higher-order object in four-dimensional space inspired by the dome of the Baptistery in Florence. Centuries later, in 1917, Einstein intuited that the universe is contained in a threesphere. Via poetry and science, Dante and Einstein arrived at similar conclusions.

And, yet, science must be kept apart from other forms of knowledge. In another column, Rovelli writes of Newton’s obsession with alchemy, the mother art of medieval Europe. Reams of his alchemical notes were discovered and bought at a Sotheby’s auction in 1936 by his fan, John Maynard Keynes, who concluded that Newton was not only among the first scientists but also “the last of the magicians”. But Rovelli points out that Newton never published on alchemy — perhaps because he found nothing of scientific interest to report. Hermes Trismegistus’ Emerald Tablet remained the enigma it had always been. ‘As above, so below,’ is not a statement worth parsing mathematically. It’s just enigmatic enough to keep you fascinated — for a lifetime, in Newton’s case. And, yet, he respected the divide between science and his other preoccupations.

Rovelli has spent the most fruitful years of his life exploring the vastness of space and time. Even for scientifically-literate readers, spacetime remains a half-mythical landscape shrouded in quantum mist, requiring elucidation by the science communicator. This series of newspaper columns, translated from the Italian by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell, performs precisely that role. It’s refreshing to learn that the Italian press, which could have got along just fine reporting on Gucci, Ferrari, Toscanini, the Mafia and bunga bunga parties, makes room — a lot of room — for science communication.

Rovelli is a child of the global youth movement of the Sixties and Seventies, a generation of thinkers, now long in the tooth, which passed around reefers like glasses of wine, drank deep of Lobsang Rampa and Jack Kerouac, and turned Timothy Leary into a global icon. “LSD was something else,” he writes, “a transformative and significant experience, to be treated with caution and respect — but one from which we could learn a great deal.”

That revolution failed, and now powerful individuals and their transnational networks have a firmer hammerlock on the world’s wealth while millions sink into poverty. Rovelli digressed and was waylaid by Paul Dirac’s 1930 classic, The Principles of Quantum Mechanics. Coming face to face with the raw reality of the universe was better than drugs. It opened the door to a career in the mysteries of the universe. And being a good scientist, he remained interested in all that the world contains.

Most of Rovelli’s columns are Eurocentric, since they were written for Italian readers, and they offer insights that may not occur naturally to the Asian mind: “The years that Copernicus spends in Italy include those in which the twenty-three-yearold Michelangelo sculpts his Pietà and Leonardo da Vinci tests his flying machines and paints his Last Supper.” When he ventures further, though, it is sometimes to his peril. He quotes Churchill writing in 1958: “If, with all the resources that science has put at our disposal, we are still unable to defeat hunger in the world, we are all culpable.” Churchill was damnably culpable for the last Bengal Famine of 1943, but Rovelli seems to be unaware of the irony.

As a good scientist, Rovelli declares he’s an atheist, but on a journey without maps in Africa, he reveals himself to be mystical and agnostic, as people working at the edge of knowledge should be: “And for a moment, despite being a fully-fledged atheist with no hesitation, I feel that I understand what it means for so many people to abandon themselves to the total omnipotence of a God who is not a father, but is the true and complete Absolute.” That’s not saying that science doesn’t have all the answers, but that the questions it addresses are too large for the human mind.

Rovelli recalls a dinner where he was seated beside Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar — memorialised in the Chandrasekhar Limit: “In the middle of the meal he turned to me and said: ‘You know, Carlo, in order to do good physics …’ My eyes widened, and I froze in anticipation of some priceless, oracular gem. ‘… in order to do good physics, what is needed most is not to be very intelligent.’”