Book : Words For Birds: The Collected Radio Broadcasts

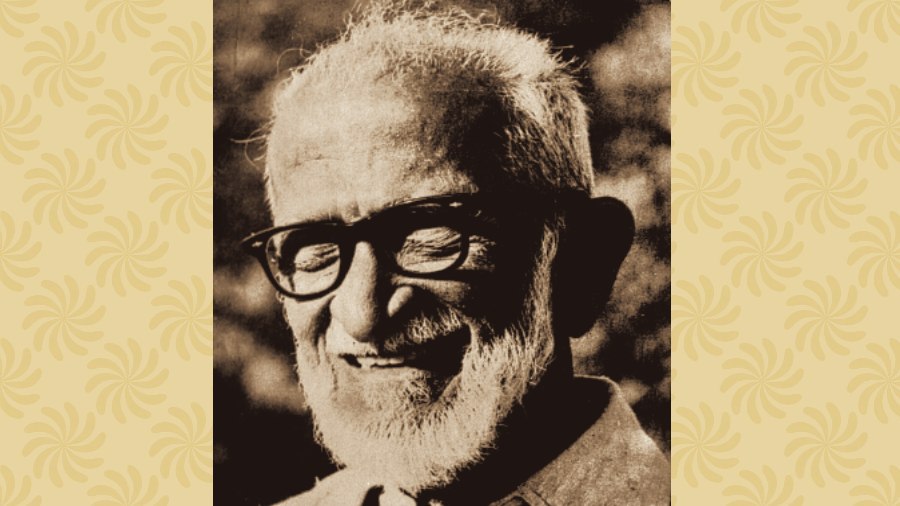

Author: Sálim Ali

Publisher: Black Kite

Price: Rs 599

Time and again in the course of my experience as a bird-watcher, I have fallen in with persons who have left me with a feeling, as they withdraw, that they were inwardly tapping a pitying finger on their foreheads. Their first glimpse of me very often has, it is true, been of a distinctly shabby khaki-clad individual of the garage mechanic type, wandering leisurely and rather aimlessly about the countryside and surreptitiously peeping into bushes, and holes in tree-trunks and earth banks.” This charming piece of self-deprecating tonguein-cheek candour sets the tone for Words for Birds, a collation of the transcripts of thirty-five radio talks delivered by the ornithologist, Sálim Ali, between 1941 and 1985.

Sourced from the archives of the Bombay Natural History Society and meticulously curated by his former student, Tara Gandhi, this commemorative volume interspersed with rare vintage photographs marks the occasion of his 125th birth anniversary. Ali needs no formal introduction as India’s foremost Birdman and his pioneering contribution to avian field surveys, natural habitat protection and wildlife conservation long predate the current global buzz around ecology and environment. The talks delivered over the course of a little less than half a century cover a wide range of topics, such as bird habits, their habitats, migration patterns, courtship techniques, nesting methods and their crucial, yet sometimes unforeseen, role in maintaining the delicate balance of nature. For those familiar with Ali’s writings, Words for Birds brings back memories of his autobiography, The Fall of a Sparrow, The Book of Indian Birds or even the Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan.

Ali’s explicit aim in delivering these talks is to “interest listeners, in the first instance for the healthy pleasure and satisfaction bird watching affords rather than for its intrinsic scientific possibilities”. This purpose is more than successful for the ease with which he wears his formidable scholarship and practical experience is, to a large extent, complemented by his engaging conversationalist style that appeals to both the veteran ornithologist and amateur birdwatching enthusiast.

The editor divides the talks into five segments — “Watching Birds”, “Seasons for Birds”, “Learning about Birds”, “Birds at Risk” and “Nature in India” — although they can be read in any order for narrative continuity is hardly the point here with each talk reading like a separate story told in an inimitably witty and effortlessly lucid manner. Ali’s eye for detail and his ability to invest nature with almost human qualities are unparalleled, witnessed, for instance, in his oft-cited observation on the Indian Baya or weaver bird: “While the owner of a half-built nest was away with a party of fellow-builders to procure fresh grass strips… I observed his neighbour, who had stayed behind, surreptitiously hop across to the unattended nest and tug feverishly at two or three of the interwoven strands.” Ali soon discovers that this pilferer was the “only laggard in this industrious colony” and a “habitual offender” who “showed every evidence of guilt and sheepishness in his actions” through his “hurried pulls”, “furtive glances” and “hasty departure[s]” in response to the return of the rest of the colony. The deus ex machina comes in the form of the aggrieved bird returning “rather unexpectedly to the scene” and catching the “robber red-handed”.

Just as this light-hearted aside is only incidental to his larger, indepth discussion on the unique nesting method of the Baya, so too the book provides a wealth of scientific information on various bird and animal species. Thus, the reader gets to know that “warm-blooded animals in the northern hemisphere… grow progressively larger as they range from the equator to the pole” since “larger body size offers a relatively smaller surface” and allows for better heat conservation in colder climates. Contrary to popular conception, Bayas do not catch fireflies and stick them into blobs of mud to light up the insides of their nests — birds occupy nests very briefly for breeding purposes and certainly not for sleeping. Or that the elaborate courtship display performed by the male peacock is not entirely explainable through the theory of sexual selection.

Notable too is his erudite discussion on the “clockwork regularity” with which mass-scale avian migratory movements take place over “trackless land and sea”, a subject he keeps on returning to in many of his talks, or his description of the rich biodiversity of specific ecosystems, such as the Rann of Kutch (“Flamingo City”), Sikkim or the Chilka Lake in Orissa. Yet, such factual data are also offset by moments of lyrical intensity as when flying sunbirds are compared to “gems in the sunshine” or the sight of nesting flamingos to a field of “white and pink flowers”.

Words for Birds provides not just a guided scientific excursion into the diversity and the abundance of life on earth but also an aesthetic appreciation for nature and its sublime and secret ministry. Coming from a scientist that’s no mean feat.