Sometimes philosophers tend to be like palm trees — you keep craning your neck upwards only to see the flourishing fronds reaching up and touching something beyond you. For they talk upwards and out, and you have to be bright enough to grasp at their ontology.

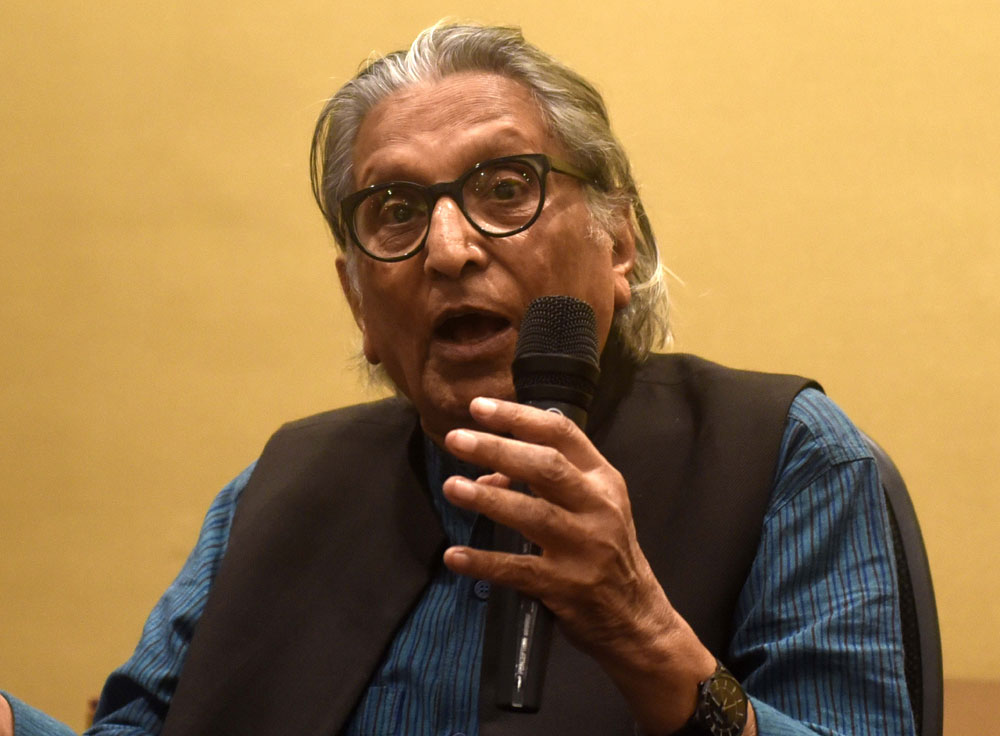

Not so, Balkrishna Doshi — the philosopher-architect. For someone who has attained more than treetop heights with the conferral of the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize 2018, he can be disarmingly down to earth, putting forth his views in a combination of childlike wonderment and humorous gravitas. In fact, as I launch into the interview, he gets into a back-to-basics mode, calling for people to return to their childhood, garner lessons from nature, and never lose the sense of curiosity. Something that continues to propel this nonagenarian — diminutive of height, dapper of style, who has a larger-than-life meld of ideology and aesthetics.

The greatness of Balkrishna Doshi is that he does not forget the previous interactions we have had, courtesy Harshavardhan Neotia, at the inauguration of his unique multi-tiered housing designed by Doshi for several levels of society with its vast swathes of open space; then at one particular sit-down dinner, when he asked what I was writing about at that time and my mention of Antoni Gaudi caused him to go into a long natter about how some of his own work had been influenced and inspired by this extraordinary architect; and he even recalled a piece I had done nearly two decades ago. When he had envisaged cities of tomorrow to be linear ones and places of living where the quality of life becomes a majority player, and you thought beyond your lifespan.

Shaping the discourse of architecture

Balkrishna Doshi — the only Indian to be awarded this laureate till date, a prize that is considered to be the equivalent of a Nobel in architecture, came in for the highest praise from the Pritzker jury. Recognising “his exceptional architecture as reflected in over a 100 buildings he has realised, his commitment and his dedication to his country and the communities he has served, his influence as a teacher, and the outstanding example he has set for professionals and students around the world throughout his long career”; and “demonstrating substantial contributions to humanity, for over 60 years”.

We quote some more from the citation to show the depths of Doshi’s persona that they have trawled: “Doshi has created an equilibrium and peace among all the components — material and immaterial which result in a whole that is much more than the sum of the parts. Balkrishna Doshi constantly demonstrates that all good architecture and urban planning must not only unite purpose and structure but must take into account climate, site, technique, and craft, along with a deep understanding and appreciation of the context in the broadest sense. Projects must go beyond the functional to connect with the human spirit through poetic and philosophical underpinnings.”

And most significantly, the award citation declared that “Doshi has been instrumental in shaping the discourse of architecture throughout India and internationally. Influenced by masters of 20th century architecture, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, and Louis Kahn from the United States, Doshi has been able to interpret and transform architecture into built works that respect eastern culture while enhancing the quality of living in India. His ethical and personal approach to architecture has touched lives of every socio-economic class across a broad spectrum of genres since the 1950s.”

The video of the event showed, too, the reverential laudation from those present on stage. It was from what he said in his acceptance speech, that we found his phrase “My work is an extension of my life, philosophy and dreams.” He also talked about an open-door philosophy, and creating the virtual trinity.

What did this signify, we surmised. That’s when he brought in the three-dimensional statue of Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva — who look at all sides. “Without the trinity” he felt, “your vision would never be a world view. If we do not have the multidimensional vision, or the temperament, at doing what you are best at, can you achieve anything?” He even took this analogy to the corporate world, where the trinity idea is to think-transform-complete.

Architecture is a backdrop that ‘proactivates life’

It is his world view that has seen him create over 100 projects, whether it be institutes of management, or design centres, low-cost housing designed to establish a sense of community and facilitate harmony between the built environment and its inhabitants, or his own home with its spatial sensibilities, and iconic roofscape or even the quirky Amdavad Ni Gufa, which was a jugalbandi creation between Doshi and M.F. Husain, a quaint cave-like structure where the artist has painted right into the ceiling. And, of course, his own design studio Sangath, meaning moving together through participation, whose activities go beyond designing homes and offices, to deep research by his Vastu Shilpa Foundation through “exploration of artistic, social and humanistic dimensions of technology”.

Balkrishna Doshi glows with pride as he tells of his house, being classified as one of the 34 most important houses of 20th century. And his office, Sangath, having been named among the 125 top international architectural buildings of the past 125 years by Architectural Record , a monthly magazine dedicated to architecture and interior design based in New York.

When we ask him to share the new vocabulary he has created with harmonising of history and culture, local traditions and the changing Indian scenario, this master of philosophical simplification says: “Every day trees change, I take my lessons from nature, from the celebrations, fluctuations and opportunities.”

Then we want to know how, in his own view, celebrating architecture can be a life nourishing event. How do you manipulate space, form, structure, character and deliver something that meaningful? His easy take: You transform space by your own thought and according to the events that take place.

But it is only when we press him to talk about his idea of a utopian India, and how cities should be shaping up today, that he points us to Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, one of the most enlightened kings of eighteenth century India and whose passion for astronomy is evident to anyone who has seen the observatories — the five Jantar Mantars that he constructed, with the one at Jaipur featuring the world’s largest stone sundial.

Doshi stresses on the importance of such wise men, and kings of the stature of Maharaja Jai Singh, who brought the cosmic notion of the world right into the heart of the city for all to access through these observatories to study space and time, with the naked eye. He was a far-sighted ruler who, among other things, shaped the city of Jaipur, a highly planned city (whose chief architect, incidentally, was a Bengali — Vidhyadhar Bhattacharya). Doshi talks about how the Maharaja sourced and developed people who had skills, craft, musical knowledge, who would produce and create a market, that would subsequently lead to business flourishing, all the while looking at providing schools, parks, health centres, and ecological houses. He wants the leaders of our country to hark back to the planning of such cities.

For, in his own words, as he said in his acceptance speech, architecture is a backdrop, which “proactivates life when in tune. It heightens all the events to their ultimate sensations, such as light, space, form, structure, texture, colour, rhythm and heightens our skills and catalyses events and rituals.” Doshi loves his river analogy, and he likens his own evolution to its flow. “The story of my life has been constantly absorbing, evolving, reflecting, changing, moving slowly becoming one again as if a calm river gushing slowly towards the unknown ocean.”

It is an ocean of learning for the subsequent communities of architects, who could take note of this philosopher-poet’s words, talking of what people aspire to: “Dhan, dhanya, samruddhi, shanti.”

It does not end there, for he continues to be a teacher, a philosophical guide, an architectural supremo. He may have titled his book Paths Uncharted, but he has charted the course of architecture, as a “sage of the profession,” that he was alluded to at the Pritzker award ceremony.

Sangath Architect’s Studio in Ahmedabad “has become a sanctuary of culture, art and sustainability where research, institutional facilities and maximum sustainability are emphasised” VSF