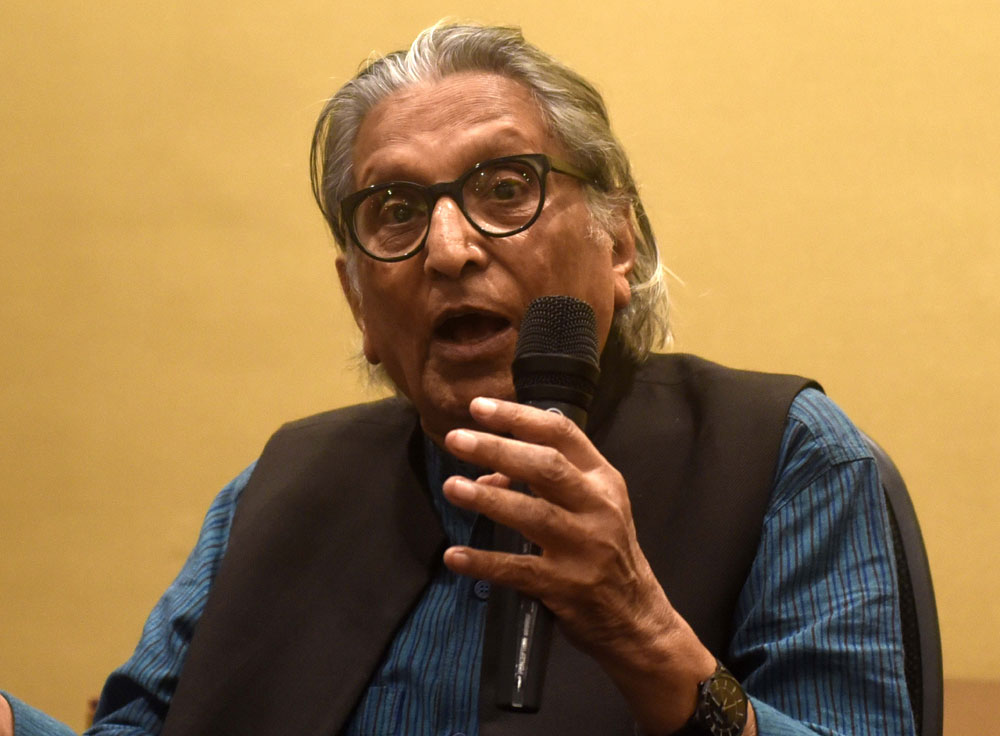

Das teases out a neat linear tale. He eggs Doshi on to elaborate on his experience of working with Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French architect who is known to have prepared the master plan for Chandigarh, among other things.

Doshi had dropped out from the school of architecture at the end of the third year. He says, “When I wrote to Corbusier requesting him to let me work with him, I got a letter saying I could join him as a trainee but there would be no pay for the first eight months.” Doshi accepted the offer and from 1951 to 1954 worked with the maestro.

And what did you learn from him, asks Das. “In broken English he would describe how people move, as one would observe ants on the ground. Then he would create obstacles — walls, columns. He would explain the minds of men. When you look at temples, buildings, you will see that there is a pattern of movement that is dictated by our moods. We never think of that. Architectural spaces create moods, dimensions and thoughts. They create stories and you begin to think of architecture as another living entity. That was my most significant learning from Corbusier,” Doshi replies.

Big names recur right through Doshi’s life, experiences and anecdotes — Husain, Vikram Sarabhai, Louis Kahn — but then it is a giant’s life. Kahn, with whom Doshi worked on the design for the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Ahmedabad, was apparently an austere man.

Says Doshi, “He would have only boiled potatoes and fish. If he bought a fabric for his wife, he would examine it to see how simple and clear it was. You see, he was thinking the other way round. You practice austerity and you find from that the zen.” Doshi turns to Das and tells him that Kahn considered Corbusier his guru. “He came to see the Chandigarh Assembly and remarked, ‘How can anyone freeze a dream like this?’”

Das himself is a conservation architect. He has worked on the restoration of the Town Hall in Calcutta and is currently restoring St. Paul’s Cathedral in the city.

He gets Doshi to talk a bit about Sangath, the design studio he built in the 1980s. Says Doshi, “I thought of doing a sustainable building and I wondered should the office look like an office? Or can the building help people experience what I want to say?”

The audience listens with rapt attention, the specifics, the architecture-talk is important, but more important is the philosophy that is its foundation. And that’s how it is with every talking point that evening.

Doshi starts to talk about Aranya, a low-cost housing society he has designed, but the point he makes is this: “Social change can be brought in, we can enhance social cohesion, we can enhance relations between generations. And I think that is a possibility with architecture.” The Aranya housing in Indore fetched Doshi the Aga Khan award in 1996.

Aranya, which is a definite departure from his other townships, was built to replace slums. Doshi conceived it as “a balanced community of various socio-economic groups”. That day he spoke about how, over the years, Aranya has morphed from being a sprawling red brick architectural spread with its streetscape, small balconies and front steps, into something quite different. He said, “That is because once you give people a chance and once they think they have the opportunity to earn more or live better, they will invent.”

From the balconies of Aranya, the audience is transported to the sprawling greens of IIM Bangalore, one of Doshi’s favourite projects. He apparently managed to convince the authorities into building the institution like a south Indian temple. He said, “The stone building is now covered with vegetation and green. It has changed the temperature and climate [of the place] but more than that, when students walk into this space, there is an unknown inner transformation.”

In his closing speech, Das said, “You cannot add or take away anything from Doshi’s creations… they are simple, yet they are deep.” Talk done, as the frail elder rose from his seat, the audience rose in a hushed and venerable silence, obviously moved by the architect’s words and perhaps a tad in awe of the spaces he had unlocked — in their minds.

The artist and legend M.F. Husain met Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi and asked him to build a gallery for him. Doshi agreed but then Husain annoyed him by calling him a “traditionalist”. The 92-year-old Pritzker laureate — Pritzker is the Nobel equivalent for architecture — told his tale in a quivering voice that evening, even as his hotel-hall audience in Calcutta’s Salt Lake strained their ears to catch every word he said. On the dais with him was his interviewer, architect Partha Ranjan Das.

Doshi continued: “I told him [Husain] I will build something where you cannot paint.” And Gufa was born — one of Doshi’s experimental designs. The underground art gallery in Ahmedabad has domed structures that are propped up by irregular columns. Husain tried to hang his works, but they just wouldn’t stay. Says Doshi, “And that is how he decided to paint the ceiling.”