Like many Indians, a young businessman keenly awaiting the fine print of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self-reliant India Mission) placed himself before a television screen around 4pm on Wednesday.

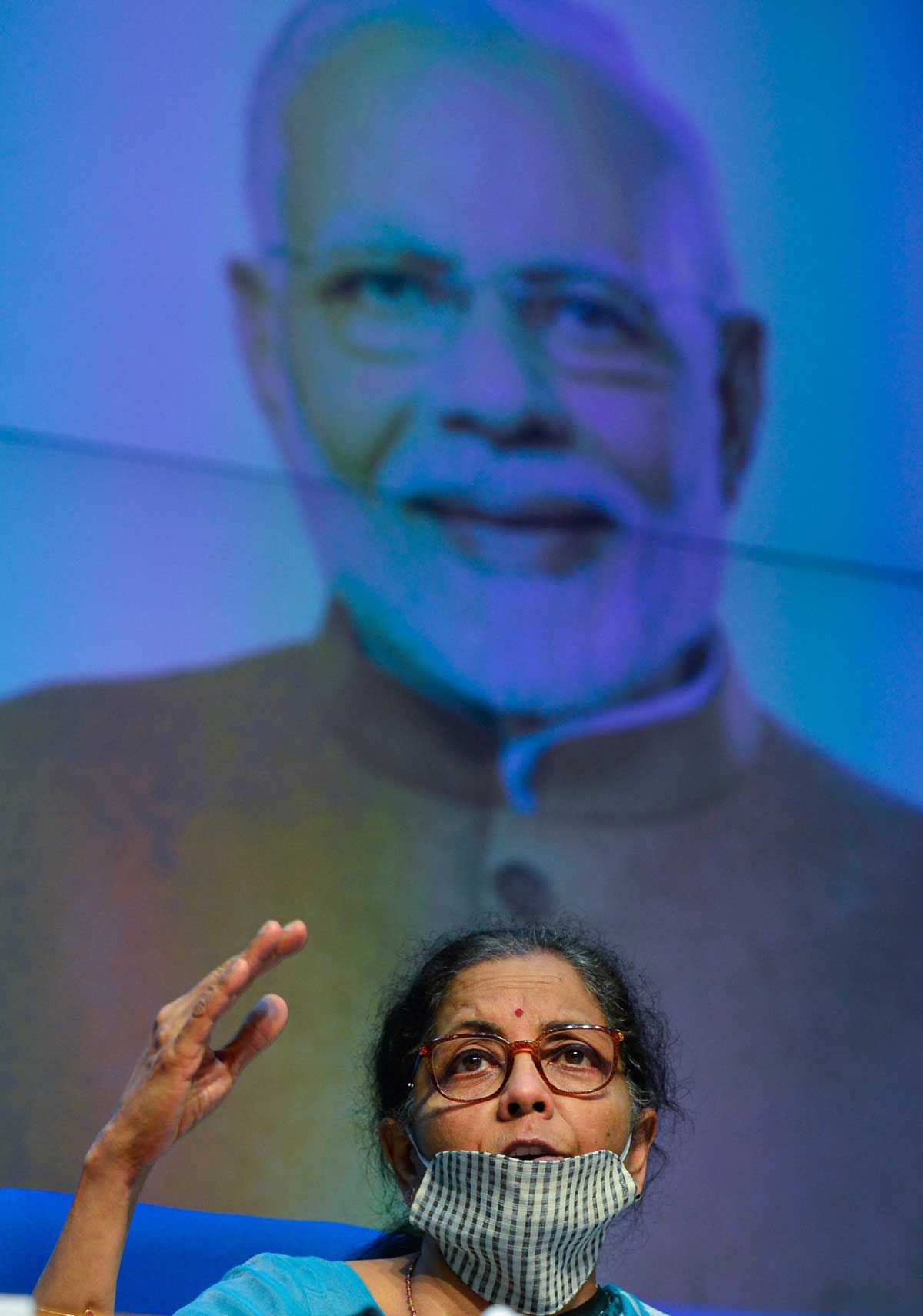

The businessman did not have to brush up his language skills to understand finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman but he came away with a sense of déjà vu.

“I heard that I will have easier access to credit but I have already had that,” said the second-generation businessman whose engineering unit on the outskirts of Calcutta has been shut for 50 days.

He said several banks had been chasing him with loan offers, which he has been refusing as he does not have enough “works” (projects or orders) to make use of the money.

Indication that credit off-take — or the lack of it — has become a big bother came from the finance minister herself during the question-and-answer session that followed her televised media conference. She said customers were urging the banks not to disburse loans even after getting them sanctioned.

“I wish there were announcements on big government spending, which would have given me an opportunity to work and expand my business…. I will need loans then,” the businessman added.

Another railway contractor, a veteran, confirmed that work from the railways had declined in the past four to five years. The disappearance of tenders has forced him to look for business opportunities beyond the gigantic public sector utility.

As he saw it, the young businessman said, Sitharaman tried to offer a supply-side solution to the crisis facing the Indian economy but he was awaiting a demand-driven way out of the mess.

The young businessman is not far off the mark. Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee, who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2019 with co-researchers Esther Dufflo and Michael Kremer, told The Telegraph on Wednesday evening: “I want to see how the government is going to create demand…. We will have to wait and see how much money goes to creating demand.”

Unlike the Opposition parties, which criticised the pace of the government’s announcements, Banerjee said that it was a “good thing” that the government was taking time to work out the details of the package instead of hurrying.

In terms of numbers, finance minister Sitharaman announced a liquidity package of Rs 6 lakh crore with the hope that businessmen like the contractor mentioned above would use it and the economy would chug along a growth path.

Fulfilment of this expectation, however, is going to be easier said than done, according to some economists.

“Yes, there is a demand and a supply side story here. Because of the unique nature of the crisis, normal business activity has slowed down or stopped completely, yet firms have to stay afloat. So the terms and conditions of these loans would matter a lot, otherwise, enterprises will be saddled with debt with no obvious horizon as to when normal activity can ensue and they can see net earnings go up,” said Maitreesh Ghatak, professor of economics at the London School of Economics.

One swallow doesn’t a summer make. The finance minister has promised to roll out more packages over the next few days and the young businessman may yet come across announcements he has been waiting for.

But the first day of details-sharing appeared not to match the expectations of many for several reasons.

First, Sithatraman started the news conference by iterating that the government had responsibilities towards the “poor, needy and migrant workers”, but the 15 measures she announced offered hardly anything that would directly benefit these groups.

With finance minister having earlier said the government didn’t want “anyone to remain hungry or anyone with no money in their hand”, there were expectations of a swift announcement of relief for the countless people heading home in extreme adverse conditions.

“There was an expectation of enhancement of the cash transfer programme,” said Left economist Prasenjit Bose.

The Centre may still announce help for the migrants but the absence of urgency has confounded many.

Second, the finance minister avoided questions on the details of how the Rs 20 lakh crore would be mobilised and spent, and on the fiscal implications of the package. She asked everyone to wait for her next round of briefings.

Given the norm that the size of a stimulus is measured in terms of how much the fiscal deficit expands over its pre-stimulus value, Sitharaman has her task cut out as not only the size of the package but India’s fiscal numbers are also going to be compared with those of other countries.

“A more transparent break-up of the spending is essential to understanding its effectiveness and its costs, such as its impact on the fiscal deficit,” said Ghatak.

The fiscal deficit is the difference between the government’s revenue receipts plus non-debt capital receipts and the total expenditure. It therefore reflects the total borrowing requirements.

Based on the details the government has shared till now, Bose said: “Going by the enhanced borrowing requirement of Rs 12 lakh crore announced recently, the stimulus appears to be a mere Rs 4 lakh crore, which is 2 per cent of GDP.”

Third, the announcements bore hints that the government was more interested in playing the role of a guarantor -- the fiscal cost of Rs 6 lakh crore of liquidity that the finance minister announced would not be more than Rs 50,000 crore, according to a senior economist of a multinational bank -- instead of playing the role of an engine of growth at a time the nation’s output is projected to decline because of the pandemic.

If the nuts and bolts of the package are still a work in progress, an economist with a leading bank said it was not too late for the government to make a course correction on the package.

“Even the governments run by conservative and Right parties are coming up with fiscal packages without thinking about their debt burden…. In this hour of crisis, the Modi government should also not bother much about the debt burden and spend more to create demand. There is still time to tweak the deal,” he said.