TRAVELLERS IN THE GOLDEN REALM: HOW MUGHAL INDIA CONNECTED ENGLAND TO THE WORLD

By Lubaaba Al-Azami

John Murray, Rs 1,999

The advent of European mercantilism, its ensuing colonial enterprises, and their regional sociopolitical impacts and histories are well-studied domains. Lubaaba Al-Azami’s book provides further insight into how Mughal India was a contested market for several European nations and charts the chaotic — yet opportunistic — rise of the English to eventually govern the Indian subcontinent. Al-Azami focuses on the period before this British dominion was established and carefully collates the early attempts by the English to obtain a toehold for trading in this region. She contends that this drive for India’s spices, dyes and textiles would eventually transform a small island nation by connecting English trade enterprises to the world and enabling globalisation to take root.

The overarching historical significance of the British empire and the ramifications of its dissolution in the Indian subcontinent are well-documented. A thinner discourse, however, exists on the early intrepid travellers from England to India who came to escape religious persecution, promote Christianity, seek trading farmans or achieve fame by documenting their adventures in this exotic eastern land. Al-Azami weaves together several contemporaneous strands to posit the changing political landscapes in Mughal India, England and continental Europe and highlights individual as well as collective efforts that sought a share in the riches of the most prosperous empire of the early modern period.

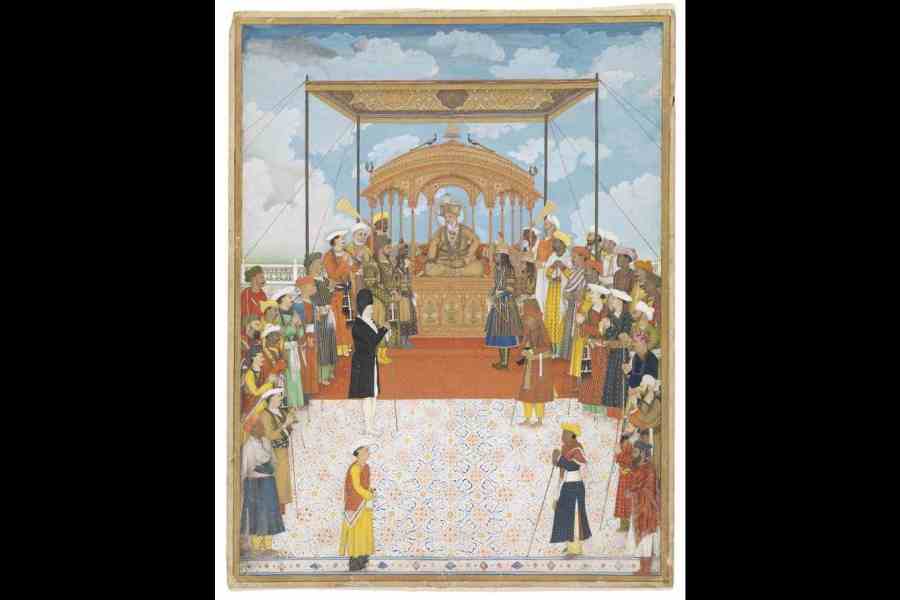

As Protestant England under Elizabeth I pursued trade and treaties with the Moroccans, Ottomans and Safavid Persia to circumvent Catholic European realms, the English gaze turned further east with the formation of the East India Company by a royal charter for trading in the East Indies. Yet, early English efforts were resisted by long-established Portuguese strongholds that held a century-long head start after Vasco da Gama’s journey to Calicut. Dutch reprisals in the Malay Archipelago too forced the English to be wary of their trading activities. Repeated entreaties by English ambassadors at the courts of Akbar, Jahangir and, then, Shah Jahan progressively elicited trading permits for the East India Company but these were also often dismissed or held in abeyance. The East India Company too went through several upheavals and crises, being sabotaged by pirates, privateers and royalists, almost leading to its dissolution during the English Civil War. Be it ill-advised forays into India’s political landscape, hasty seizures of Mughal cargo or being caught in the crossfire between Maratha and Mughal forces during Aurangzeb’s Deccan campaign, the Company’s enterprises often looked bleak. Al-Azami comments that it is remarkable how the positions of power later underwent complete transformation from these early English pleas for subsisting their business interests while jostling with long-entrenched continental rivals to the eventual rise of the British empire that monopolised both goods and governance.

What the book notes intriguingly is how little the initial English traders had to offer in exchange for spices and dyes. Heavy woollen broadcloth from England evoked scarce demand in tropical climes. The English contrived upon trading textiles from India for spices in Malaya, using silver bullion to purchase their requirements. Trade in ivory and slaves from Africa and tea from China further buttressed this spice trade and the Company’s growing clout in India. Its factory at Surat and its fort in Bombay, gifted to Charles II as dowry by the Portuguese, enabled further expansion. Thus, a global network for exchange and movement of commodities became established, linking Asia, Africa and the Americas, all underpinned by India, the jewel in the English crown.

The book sheds light on several interesting characters. Father Thomas Stephens who came to further Jesuit missionary activities and composed the Kristapurana in Marathi; William Hawkins met Jahangir seeking trade allowances and ended up marrying Maryam Khan from the Mughal zenana; the search for fame through his travelogues drove Thomas Coryate to undertake journeys across India and assimilate himself into its culture. Al-Azami also details how the ladies of the Mughal court like Maryam al-Zamani, Nur Jahan and Princess Jahanara oversaw colonial trade in India and undertook their own mercantile pursuits. The eventual growth of the Company alongside the Mughal decline and substantial Indian territories being subsumed into the wider British empire were scarcely contemplatable at this stage. That the English were opportune enough to seize their chances to do so changed the historical path that the subcontinent’s fate may have otherwise taken.