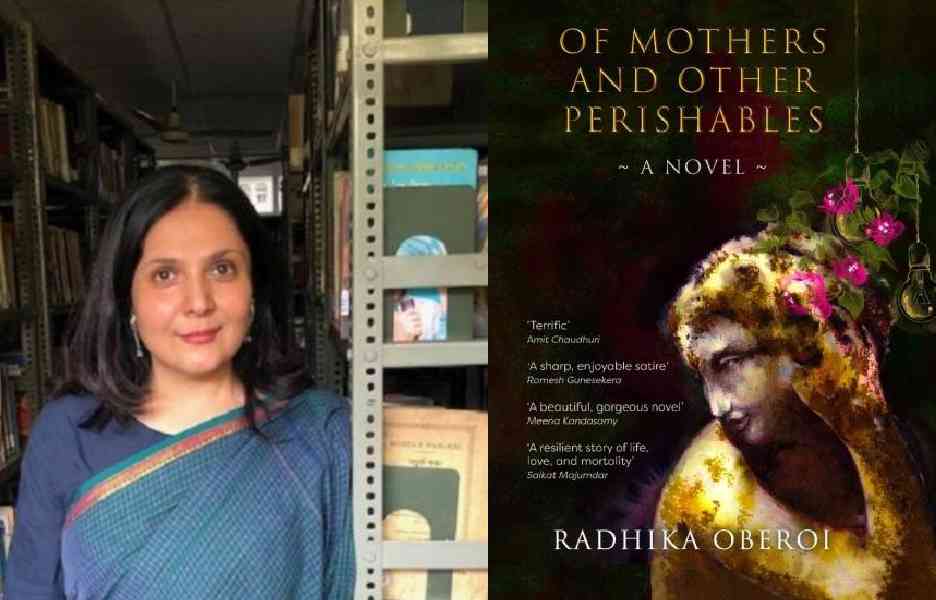

Author Radhika Oberoi takes the reader by surprise with her innovative and inventive brilliance and beguiles with the unique refashioning of language and the creation of personal history through the vision of a dead narrator. In an exclusive interview for t2, Oberoi talks about her novels old and new, her shift from advertising, motherhood, and more. Excerpts.

The reader is immediately hooked by the concept of a dead woman telling the story. How do you configure this ability to think outside the box in conjuring the powerful images which hold the reader in thrall?

You’ve plunged into craft right at the outset, and that’s interesting! When I was working on Of Mothers and Other Perishables, I was preoccupied with ideas of decay and mortality, and wanted to convey those in a unique manner. I was also interested in memory, and how one’s recollections are at once vivid and imprecise — one might recall the flavour of a strong cup of tea or the colour of a hand-knitted sweater, but forget the exact date of a particular personal event, or the exact time when one fell in love with someone, etc.

The idea of space is uniquely conveyed — the storeroom from the first few pages. There is a geography here that is thrilling and each object is like a landmark. How do you use this method in marrying history and geography?

Yes, this novel is strewn with objects — old letters, vinyl records, a turntable, a torn leather suitcase, saris — a dead person’s worldly belongings. Each object has its own history. Each object is a nostalgist’s treasure, a time machine of sorts, which allows one to recollect and perhaps dwell in a different era, a mellow spot in memory. The storeroom too, a narrow space in physical dimensions, is actually an elastic geography — it expands to include one’s childhood, it contracts into the present, depending on the mood of both the dead narrator and her daughter who frequents this space. So, personal histories are intertwined with geographies both real and of the mind.

This idea of the past creeping into the present and future seems to be a signature of your telling of the story.

Memory isn’t linear; the past resurfaces in fragments. Several novelists play with this idea of imprecise recall to create ‘non-linear’ narratives that blur timelines and have choppy narrative arcs. This allows for stories to merge — the past infiltrates the present and vice-versa, creating narratives riddled with fault lines, memorable characters, layered fictions.

In your first book, Stillborn Season, did you experiment with this smudging of time past and time present?

Thanks for bringing up Stillborn Season! It’s actually a novel-in-stories, with multiple narrative voices. It does experiment with time, language and traditional narrative arcs. The first half of the novel is set amidst the riots that erupted in Delhi in 1984, immediately after the assassination of [the then] Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The second half is a retrospective gaze at this terrible and terrifying history. Each chapter has a new narrator to create a sense of unreliability. I’ve also experimented with linguistic styles and syntax, for instance, a prisoner’s lament has the urgency of telegrams, a tormented sub-inspector has a unique diction. To offer symmetry or order amid the chaos, the novel has a prologue and an epilogue, both set in the garden in which Indira Gandhi was shot dead by her Sikh bodyguards.

How did you move to writing from advertising?

When I joined advertising, on the cusp of the 21st century, copywriting was still about the power and beauty of the sentence (in the English language). Copywriters still fretted over writing perfectly sculpted headlines, and some of the finest long-copy ads read like great short stories. I remember reading The Copy Book and discovering David Abbott, Neil French, and so many other advertising superstars. Of Mothers... mentions and celebrates the 1959 ‘Think Small’ ad campaign for the Volkswagen Beetle, created by ad firm Doyle Dame Bernbach.

Back home, I was influenced by Indian copywriter Alok Nanda’s Mauritius Tourism campaign, and Vidur Vohra’s work for Wildrift Adventures. My early encounter with brilliant ad woman Syeda Imam — a whimsical, charming creative head — taught me that leadership can also be gentle, graceful and delightfully idiosyncratic. Advertising has changed considerably since then. Its focus on 30-second TV commercials, primarily in Hindi and, now, hastily-produced digital stuff, has led to a lot of writers exiting the industry to finally write their books and tell their stories.

Tell us about your idea of motherhood and how you configure woman power in a patriarchal society such as ours.

It’s interesting how the notion of ‘motherhood’ slips into stereotypes. Mothers are still meant to be an endless fount of love and understanding. Fathers are still typecast as providers and disciplinarians. And yes, our society is still very patriarchal. I feel great stories emerge when parents, either in real life or as characters in fiction, defy expectations. So, a father can be a source of maternal love too, and a mother may crave a life outside the home — wealth, fame, and power!

Who are the writers who have an abiding influence on your work?

Several writers have influenced me and, perhaps, crept into my work. I’ll name a few, in no specific order: Zadie Smith, Rohinton Mistry, Amit Chaudhuri, Arundhati Roy, Emily Brontë, Charles Dickens, Paul Theroux, Salman Rushdie, Maggie O’Farrell, Rainer Maria Rilke, Gabriel Garcia Márquez, Franz Kafka… I could go on and on. I love them for their sentences, their inventiveness, their recreations of history, their empathy for flawed humans!

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College