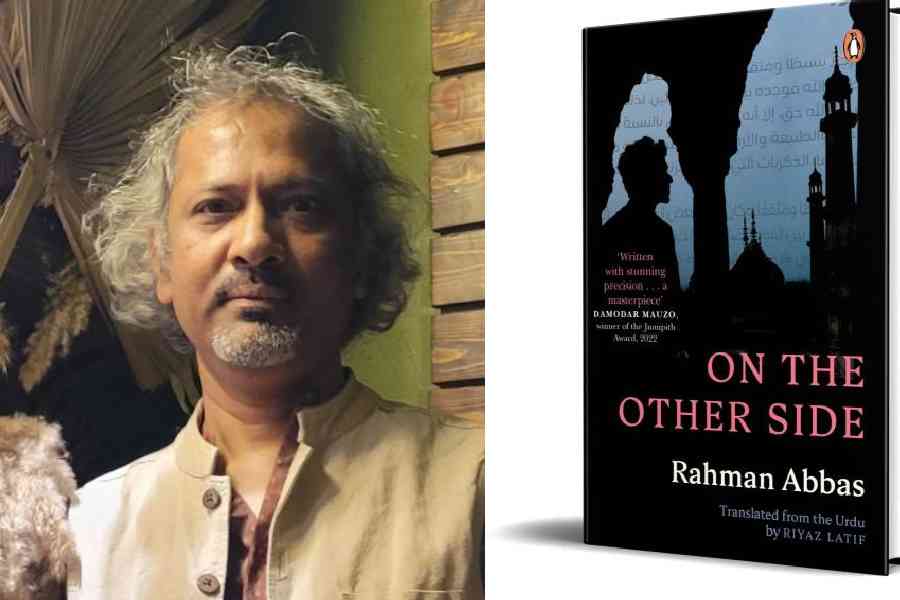

Urdu novelist Rahman Abbas’s Khuda Ke Saaye Mein Aankh Micholi (2011), translated into English by Riyaz Latif with the title On The Other Side (published by Penguin India), mirrors society — patriarchal, prejudiced, exploitative, biased and extremely intolerant — and follows the story of Abdus Salam Kalshekar, who shares a lot of similarities with the Sahitya Akademi-winning author. Mumbai-based Abbas, who also writes in English, channels his feisty pen, just like in his previous novels Rohzin, A Forbidden Love Story, and others, and presents the complexities of a liberal mind in an orthodox society. A tete-a-tete with Abbas, who has been at the altar of justice on obscenity charges.

The character of Abdus Salam is intriguing. He is a teacher, and philosopher, in parts he is eccentric, in parts he is wise, at some point he is full of conflicts and on the other, he finds simple things deeply meaningful. Tell us about working on his character and how it grew with the book.

To be honest, I have seen contradictions in people since my childhood. We live the lives of many people in a single body. Similarly, at different stages of our lives, we become different people, sometimes we contradict who we once were. Hence, when I started writing this novel, Abdus Salam was already in my head. I just kept writing. He evolved, lived, and died without my interference in his life.

You also seem to share some similarities with Salam. To start with, he is a teacher, has a modern outlook and his writings too do not conform to any set rule. Is there any way in which Salam is different from you in real life?

Ah, yes, these similarities are undeniable. But he was not me; I’m not his reflection.

However, there is something of him in me. His eccentric traits might be present in me. The difference between this character and me in real life is — he didn’t hide his true self; I do, a little, sometimes.

On The Other Side follows an interesting concept of a book inside a book with Salam writing his Dastaan E Ishq and then another author picking it up and writing on him. What was the genesis of this idea?

Every novel should be a different world. The narrative should be unique and in accordance with the subject’s requirements. The complexity of a novel is, in fact, its beauty, but the complexity shouldn’t be ambiguous beyond one’s comprehension. To experiment with the form, find an appropriate narrative and provide depth. I had to find a way. This was the main reason why I used the technique of a story within a story.

Salam thrashes Urdu in the novel and says the language is ‘utterly deprived of the colourful exuberance, freshness and heady moods of love and sex’. He goes on, ‘The imaginative conception of women in Urdu poetry was worthless and unrealistic; it was nothing but a man’s obscene outpouring’. Also, his opinion on Allama Iqbal might raise eyebrows. What are your thoughts on both?

I share Salam’s views; he has been nakedly honest in his observations. There is no space for me to disagree with him. In front of my eyes, there is the history of Urdu fiction. In the last 100 years, Urdu fiction has not produced a single novel dealing seriously and aesthetically with the subject of love and sex — its pleasure, pain, beauty, challenges, and power. We witnessed that both the progressives and modernists in Urdu fiction failed us on this specific subject. This might be because, for them, literature was either a tool for the propaganda of communism or a struggle to uphold a nonsensical notion of absurdity as the definition of good literature. For me, the novel is a genre that investigates the deeper truths of our lives, emotions, existence, nation, society, cities, and dreams, where men and women have a natural urge for indulgence, love, happiness, and sex. Yes, there is a great tradition of powerful poetry in Urdu. However, the majority of our poets have unfortunately been unable to portray the complexities of relationships. As far as Allama Iqbal is concerned, he is one of the greatest poets but some of his ideas can be challenged, criticised, or laughed at.

The book starts with a lot of wise words and we find Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s couplets in the pages. Who has been your literary guiding light?

The ‘wise words’ used at the beginning of the book are, in fact, paradoxical or an effort to deflect Urdu readers, as the first audience of the book was Urdu readers. We know that they seldom tolerate criticism of their society and its truly bleak face. The ‘wise words’ have worked, as the book has received a huge reception in Urdu despite its harsh critique of society, puritanism, belief systems, and the constant indulgence in religious preaching.

As far as my literary guiding light is concerned, reading poetry, fiction, and philosophy has been my passion. Meer Taqi Meer, (Mirza) Ghalib, (Faiz Ahmed) Faiz, Meeraji, Rajindra Manchanda Bani, and Shakeb Jalali are part of our great tradition of poetry. In fiction, we have (Saadat Hasan) Manto, Rajendra Singh Bedi, Ismat (Chughtai), Krishna Chandra, Nayyer Masud, Syed Muhammad Ashraf, and many other amazing writers. I have learned a lot from them. However, Franz Kafka, James Joyce, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Milan Kundera, Orhan Pamuk, and Umberto Eco have also been my favourites. Yes, we read and learn from good writers, and so do I.

Your work has been called obscene for which you also had to go to jail. In fact, in the book, we find the author ruminating ‘Before embarking upon writing should a writer ask religious leaders how much literary freedom one has?’ Did that make you fiercer, or have you put your guard on?

In jail, I learned that writing is a weapon and must be used carefully. In fiction, nothing is obscene if the aesthetics are maintained. This novel also raises the question of how free a writer truly is. Our society, in general, is puritanical, and the neo-political milieu has turned our once-great liberal society into a barbaric village akin to parts of Pakistan or Afghanistan, where freedom of expression is compromised. Despite our great traditions of the Kama Sutra and the Mahabharata, we are not free enough to experiment with sexuality. All puritans have joined hands against the arts and freedom of thought. However, fiction stands in opposition to puritanism, totalitarianism, and dogma. Moreover, when I was writing this novel, the case against my first novel, Khalistan Ki Talash, was still there and, hence, I had to be careful.

In one of your writings, Manto ki Azziyat ka Ehsas, you share how you felt like Manto. Do you derive your fierceness from him, or has he been an inspiration in any way?

That article on Manto is an outcome of my recalling his trauma in jail as he faced obscenity charges many times. I think he never wrote anything obscene; he was simply born into an obscene and orthodox society. If there is fierceness in my novels, it results from the time I live in and my life in Mumbai. Additionally, my reading of great authors, including Gustave Flaubert, James Joyce, (Jean-Paul)Sartre, Albert Camus, Milan Kundera, (Fyodor) Dostoevsky, and D.H. Lawrence, has certainly influenced my approach to subjects, craft, and language.

The book starts with Salam’s story exposing a society that is lost in religion, it then gradually touches upon topics of caste, queerness, patriarchy and more in very small segments.

I cannot imagine a novel without people, places, society, traditions, and country. A novel can explore how external factors affect existence. Caste, queerness, patriarchy, and everything else in this narrative are parts of our collective lives. However, this is a small book, so there is no detail. My other novels, Zindeeq, Ek Tarha Ka Pagalpan, and Rohzin, cover these topics in more detail. Zindeeq spans almost 800 pages and deals with these and other subjects, including our history, mythology, folklore, politics, the queer movement, our past, and potential threats to all minorities in the subcontinent, including religious and sexual minorities, over the next 100 years.

There’s a particular couplet that Salam has written 23 times in his book. Does that couplet hold any significance in your life?

Yes, it’s from a ghazal by Shakeb Jalali. In fact, it is an existential question. And this question has been haunting me for years.

Riyaz Latif has an excellent command over the English language. How successful was he in translating the story from Urdu?

Yes, Riyaz Latif has command over the language and is also a wonderful Urdu poet. I might say he is an eccentric poet, sharing similarities with me and Abdus Salam. This was the only reason he agreed to translate the novel. He has been in touch with me throughout the translation process and has done an amazing job.

Lastly, what’s next from your pen?

I have already completed a novel titled Nixdaan, a Konkani word that deals with the cultural and historical aspects of food. The novel explores themes of conversion, forest life, Konkani culture, Dalit sensibilities, love, and Mumbai from 1970s to 1990s.