In her new novel, Orbital, Samantha Harvey cleverly chooses to locate her story aboard a space station that actually resembles a mini United Nations. The six astronauts and cosmonauts from the USA, UK, Russia, Italy, and Japan — two women and four men — have been sent to travel around Planet Earth 16 times in a day, whirling at over 17,000 miles every hour. Captive in their inescapable home of the space station, the reader realises perhaps Harvey is suggesting that the harmony and peace that is achieved in the microcosmic paradigm of a space station could easily be transposed back on the macrocosm of the earth.

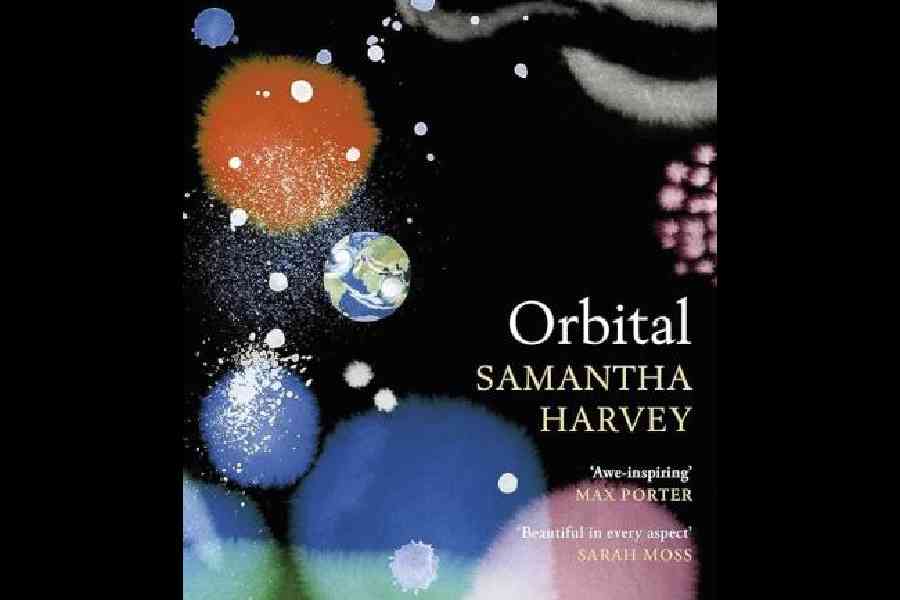

As I crack open the spine of Orbital, the sizzling new novel that has just won the Booker Prize this year, I am blown away by its freshness. It’s about how six astronauts on a spacecraft orbiting thousands of miles away suddenly realise how much they love planet Earth.

With a kind of humility and reverence to her craft, as only she can muster, Harvey states this about what makes a good book: When you close that book it gives you a sense of perfect inevitability that makes you feel it couldn’t have happened any other way. This story could not have been told any other way, says Samantha Harvey about her fifth novel Orbital.

Awash with celestial light, the story is strategically built on an unexplored idea about how diverse humans with culturally disparate experiences understand the need to coexist on a bloodied and embattled planet, precariously surviving the rapacious greed of humans and the disasters that Mother Nature must endure. Amidst the vast swathes of eternity, while news of the death of loved ones comes to the six astronauts tethered in the tightly built orbiting space station, they realise the preciousness of Planet Earth.

It is as if the writer as Mother Nature is a composite of all the six scientists on the mission. The utter urgency of the danger of losing the planet we are blessed to inhabit becomes the focus of this beautifully sculpted narrative. And the crystal clarity of Harvey’s style makes Orbital a meditation, one the reader is compelled by.

Harvey’s style matches her content. It is at once lucid and lyrical, the reader jumping straight in with the first paragraph: “Rotating above the Earth in their spacecraft they are so together, and so alone, that even their thoughts, their internal mythologies, at times convene. Sometimes they dream the same dreams — of fractals and blue spheres and familiar faces engulfed in dark, and of the bright energetic black of space that slams their senses. Raw space is a panther, feral and primal; they dream it stalking through their quarters.”

Edmund de Wall, chair of the judges, stated: “As judges we were determined to find a book that moved us, a book that had capaciousness and resonance, that we are compelled to share.” This is a book about a wounded world, he maintains. He continues: “With her language of lyricism and acuity, Harvey makes our world strange and new for us.… Our unanimity about Orbital recognises its beauty and ambition. It reflects Harvey’s extraordinary intensity of attention to the precious and precarious world we share.”

The tenuousness of human life, where news from Earth comes in the form of a death in the family or a typhoon as it gathers over an island, hits home. They are far from Earth and the inability of being a part of the present back there makes them protective of it.

Not many novels have been set in space that have been nominated for a Booker Prize. One hundred thirty-six pages slim, Orbital is one of the shortest Booker winners. The only shorter one that won this prize was Penelope Fitzgerald’s Offshore in 1979.

The space station becomes an apt example of heterotopia. The French theorists Michel Foucault and the German Gaston Bachelard might have congratulated Harvey for so effectively blurring borders between timezones, spaces and individual stories. In a fascinating piece of narrative finesse, Harvey has truly replicated Planet Earth in a space station. We understand the fragility and preciousness of life through her imaginative inventiveness. The novel synthesises the deeply sensual imagery of the romantic poet John Keats with the postmodern Pico Iyer: “Over its right shoulder the planet whispers morning — a slender molten breach of light”. There is a wake-up call where the author as a stable narrator comments: “Can we not stop tyrannising and destroying and ransacking and squandering this one thing on which our lives depend.”

A large part of this novel was written during the Covid lockdowns. Harvey admits to watching hours of online footage from the International Space Station. In an interview with BBC Radio 4’s Front Row Programme, Harvey said, “I would have footage of the Earth in low Earth orbit on my desktop all the time as I wrote. It felt such a beautiful liberation to be able to do that every day and at the same time I was writing about six people trapped in a tin can.”

Reality is embossed with cunning strategy in this fifth novel where Harvey allows the reader to feel the reality of how many pairs of socks and how many changes of underwear the astronauts go through, and the trash that is clamped down so it doesn’t fly around.

Orbital resonates with the reader because of the current precarious situation of bringing back the US astronauts Sunita Williams and Butch Wilmore, who are stranded on the International Space Station. Space X is supposed to rescue them in February 2025.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life, and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College