The current situation in the city gives rise to many questions, mostly dealing with whether safety for women in Indian society is still a pipe dream even after 77 years of Independence. In the 1880s, only a couple of years after Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Anandamath was published, Kadambini Gangopadhyay became the first woman to gain admission to the Calcutta Medical College (in 1884). Society has come a long way since then but is still somehow stuck in the trenches of animalistic pre-civilisation. Chattopadhyay, who famously wrote of India being worshipped as three different Goddesses and whose Vande Mataram is still sung every Independence Day, would be horrified to see what depths his ‘Bango Maata’ has plummeted to — indeed, every two or three years there seems to be an onslaught of public condemnation after a particularly heinous crime against a woman rocks the country, but actual addressing of the vermin infiltrating Indian mindset and society has, especially in recent years, been few and far between.

There have been multiple books written on the subject, of course; books dealing with crimes committed against women and how either justice is delivered to them or they avenge themselves. What’s more, these stories are not new — texts as old as our epics and Puranas tell of violence against women that more often than not ends in dire circumstances for either one of the parties involved.

Take the women of the Mahabharata, for instance. Many believe that one of the primary reasons why the battle of Kurukshetra was fought was because Draupadi had been unfairly wronged by her husbands and the Kauravas. Lanka would never have been set on fire if Ravan hadn’t abducted Sita, and yet at the end of the tale she is asked to take the agnipariksha to test whether she is still ‘pure’. Ahalya, lured by Indra, is turned to stone by her wrathful husband and must remain so until Ram absolves her of her curse. There are plenty of stories, across time, space and cultures, that have told and retold tales of the exceedingly damaging consequences of women being wronged. Yet their core messages seem to have been lost to time, and people only seem to remember these women at moments when they are at their weakest. For some reason, their strength and power appear to have been forgotten.

Today, a plethora of women writers are reclaiming these tales. Stories are being written and rewritten to grant more agency to wronged women. Across genres and styles, authors are reimagining narratives to grant these women their own voice, essentially uplifting their stances as passive victims of fate or cruelty into active agents of change. Contemporary literature has seen an influx of stories that turn the tables on traditional patriarchal storytelling. Authors today are revisiting old myths, folklore, historical accounts, and the classics to bring to the forefront the strength and resilience of their women, who have been portrayed as marginalised for years.

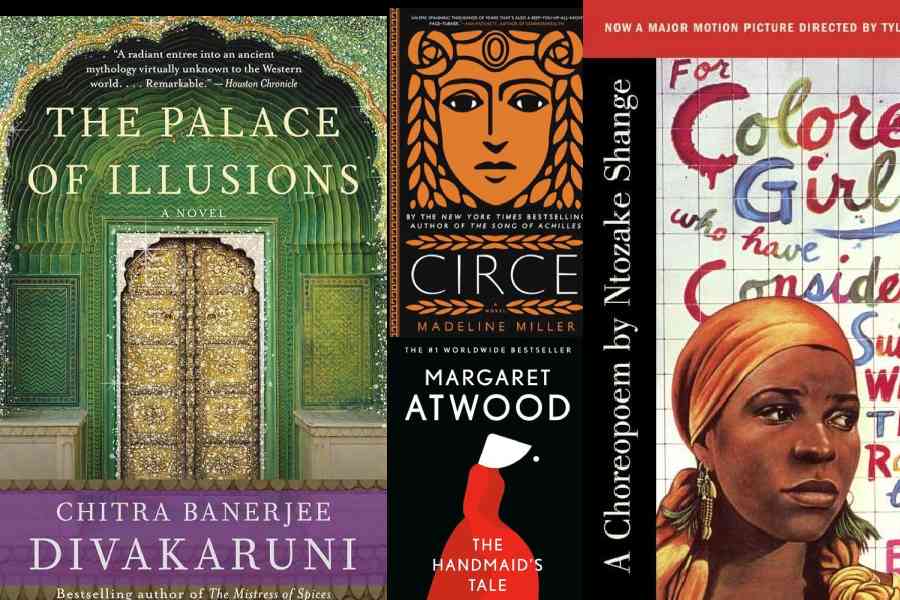

Take Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s books, for instance. The Palace of Illusions retells the Mahabharata from the perspective of Draupadi, fleshing out her story, giving her an identity beyond being the wife of the five Pandavas, and granting readers access to an entirely different relationship that they may not have paid attention to before. The Forest of Enchantments, again by Banerjee, is a contemporary feminist take on the Ramayana, which, people often tend to forget, is also a great tragic love story. Sita tells her own tale, laced with anger and joy, mirth and sorrow, victories and heartbreak. Similarly, Madeline Miller has been rewriting the tales of Greek mythology, reconstructing the story of the enchantress Circe to grant her agency and the voice that has always been denied her. Making the subaltern speak is, in contemporary times, a literary endeavour that comes with its fair share of responsibility, but it is a task that is needed. The world has descended into such grotesque realities that if our fiction does not allow space for the oppressed class to speak up, then reality never will.

Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea is a postcolonial and feminist prequel to Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, reclaiming the story of the ‘mad’ woman in the attic. Bertha Mason, locked away in the attic of Edward Rochester’s Thornfield Hall, is given a backstory, tracing her days as a young girl in a Jamaica plantation till her marriage to Rochester goes askew, he locks her up in the attic of his country mansion, and she sets Thornfield on fire.

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is one of the finest literary examples of women being treated as an oppressed class, kept around only for their reproductive abilities, and whose consent does not matter in the slightest. The Color Purple by Alice Walker is another of those tales that depict life in early 1900s America and abounds in its female characters being physically mistreated by men. The novel’s protagonist finally finds companionship in another woman. for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf by Ntozake Shange tells the stories of seven women who suffer oppression in a racist and sexist society. Dealing with very real issues of rape, abandonment, abortion, and domestic violence and weaving it all together to represent the universal and complex bond of sisterhood, there is hardly a woman for whom this choreopoem will not hit close to home.

Tellings, retellings and fresh stories of this kind have long made themselves present on bookshelves, and that is because they are required for perusal. Because no matter what genre these stories are represented in, they are products of a very debauched society. Life begets art, and these narratives serve as mirrors, reflecting deep-seated, oppressive issues of our time, where justice often seems elusive and power dynamics skewed.

Think of Gujarat. Delhi. Hathras. Hyderabad. And now Calcutta. Crimes that have taken place within years of each other, with hue and cry succeeding every single one of them, yet the cycle never stops completely. Not to mention the countless other crimes happening every other day in this country that are never talked about. Rape cases are still reported every morning, no matter what newspaper you pick up. The list never seems to end; what’s more, at this point, the fear has become integrated into our mindsets as easy as breathing. But the protest for justice, for answers, for the basic human right to live without being afraid must never end. And that is why we need literature, and the arts, to tell these stories — to remind us to question, to empathise, and to demand better from the world around us. In a sense, such tales are not just tales of revenge or justice, but direct calls to action. If nothing else, they urge readers to recognise the injustices around them and to strive for a society where these stories need not exist.