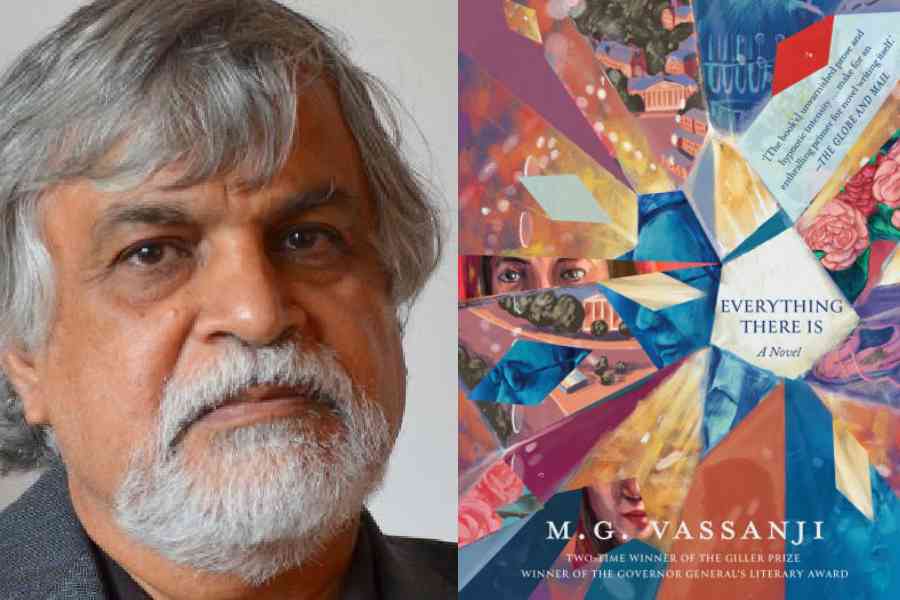

M.G. Vassanji’s latest novel Everything There Is is about everything there is in the universe, and more. Inspired by the life of Pakistani theoretical physicist Mohammed Abdus Salam who co-won the 1979 Nobel Prize for Physics for his contribution to the electroweak unification theory, this fiction novel weaves a story of aspiration, achievement, guilt and religion.

It starts off slow for the non-science readers but picks up pace as the professional and personal worlds of Nurul Islam, a respected physicist and professor at Imperial College, London, unravel in the pages. Both worlds are being challenged and the protagonist, who is working on the grand unification of forces and particles and is one half of the Islam-Rosenfeld theory, meanders through the challenges. A tete-a-tete with Kenya-born and Toronto-based Vassanji, who won Canada’s Giller Prize for Fiction for The Books of Secrets, and The In-Between World of Vikram Lall, and the Governor General’s Literary Award for A Place Within: Rediscovering India.

Your last novel was A Delhi Obsession, which is completely different from the latest novel, Everything There Is. What made you embark on this journey of Abdus Salam?

The idea for a novel comes as an inspiration. There is no plan or strategy. The idea for this novel came around 2015, I think. I wasn’t sure how I would proceed.

In an interview, you said you never met the Nobel laureate. What was it about him that intrigued you?

As a young physics student at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), all great physicists were our heroes. I was intrigued by Abdus Salam because unlike his other great contemporaries (Steven Weinberg, Richard Feynman), he not only believed in God but knelt down, as I imagined, to worship Him. How could someone who worked on and speculated about the workings of the Universe actually believe and pray, that was the question that intrigued me. Other great minds would have said, it doesn’t matter, God is not necessary, and so on.

I believe you have also used creative freedom to fictionalise his character. The lines seem to have blurred. Tell us about the process of using your creativity and moulding Abdus Salam’s character.

Once I had the idea, I simply wrote a novel, a fiction about a physicist concerned about the above question, preserving as much as I could the external fundamentals — the unification question, his Indo-Pakistani Punjabi origin, his education at Government College, Lahore, and Cambridge University, etc. With that, the character was my invention. The novel is not about Abdus Salam, it is inspired by him.

The title, adroitly, resonates with the unification theory in physics that Abdus Salam is working on and also brings into its fold, the social and political life...

Everything There Is is the universe around us, how it is composed. Of course, everything could include the personal, which is intangible, that he thinks of as belonging to another universe, which often interferes.

You also went to MIT and studied nuclear physics and worked at a nuclear facility in Canada. Do we find traces of you in Abdus Salam?

Not in terms of the physics. He was a genius. I was simply a mediocre, ordinary physicist. He was of another generation. But some of my character’s attitudes, his liberality, some of his observations, reflect my own attitudes. That’s inevitable. His attitude to nuclear arms reflects my own. Whether Abdus Salam contributed directly to Pakistan’s nuclear weapons is for me an open question. Nurul Islam (my character) is opposed to it on principle.

You were born in Nairobi, before moving to Canada, which has been a British colony, just like Pakistan and India. Did that history connect you with Abdus Salam at any level?

No. As I said, he was of another generation. During my teens, the liberation of Africa was an urgent question.

Tell us about your interest in science and literature while you were growing up. What made you pick up the pen and tell stories?

I was good at maths and physics, it seemed the easy way to go. But I also loved to read, and in school English composition was my favourite subject. My teachers liked my compositions. Even in university, I enjoyed writing essays. I even enjoyed writing my PhD thesis. Writing fiction was an occasional pastime; but when I arrived in Toronto, plagued by memories of “home” and the feeling that I might have lost it irrevocably, I started to recreate it on paper... a street with homes and characters, a city, a country.

Any literary personality who inspired you as a writer?

I admired Ngugi wa Thiong’o who wrote about his unknown (to the world) Kenyan people, brought them to life and the world. I desired to bring my people and my city to the world... to the literary table so to speak. To shout, ‘We also exist!’ I have enjoyed Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, Gunter Grass, Graham Greene for the conundrums his Catholic characters face; Tagore’s short stories; some Partition stories... I fell in and out of love with Lawrence Durrell.

What will your next book be about?

It will be a futuristic fantasy seen from the 13th century.

— Farah Khatoon

Pictures: Westland Books