PROVINCIALS: POSTCARDS FROM THE PERIPHERIES

By Sumana Ray

Aleph, Rs 899

As I was reading Sumana Roy’s fascinating book, another fascinating series of events was unfolding at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. During the Q&A session following a lecture by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Anshul Kumar, who identified himself as the founder-professor of Brahmin Studies at the university, pronounced the surname of the American postcolonial thinker, W.E.B. Du Bois, with a French accent instead of the English accent preferred by the thinker himself and, when corrected, refused to back off.

The controversy that followed divided the thinking world into two halves. One group criticised Spivak for her ‘insensitivity’ of correcting somebody’s pronunciation (‘Can the Subaltern Pronounce?’ — many news outlets and social media posts played with Spivak’s own formulation, probably forgetting it was a rhetorical question to begin with). Another group, though small, pointed out that Spivak insisted on the political charge in Du Bois’ rejection of the French-accented pronunciation of his last name. It was a complicated issue involving too many binaries for our comfort: Kumar and Spivak, French and English, Dalit and Brahmin, Delhi and New York and so on. As I kept reading Provincials, I realised that the discomfort persisted due to our own subscription to the original binary between the cosmopolitan and the provincial.

Roy cautions us against this possibility early in the book: “Provincials have been imagined as the other half of a binary; cosmopolitans are the head, we the feet”. The semblance to the mythical origin story of the four varnas is unmistakable — the Brahmins emerged from the mouth of the Brahma and Shudras from the feet. “We have not minded being feet;” Roy writes, probably with a wry smile, “it is easier to hide one’s feet than the head. The history of belatedness is, after all, the history of the feet reaching late; the head manages to reach before an appointment.”

Belatedness is a recurrent theme of the book, the untimeliness of a place, the undelivered postcard, the unfinished poem or the unfulfilled life. In Provincializing Europe, Dipesh Chakrabarty famously terms this condition the “waiting room of history” where all non-European histories wait for the train of progress to arrive from the West. In Chakrabarty’s act of returning the provincial gaze, provincialising is akin to limiting the universal appeal of any category of thought that emerged in the specific history of Europe. Roy asks instead if it is possible to think of the provincial not as a limiting/limited space but as a periphery that does not necessarily surround a centre.

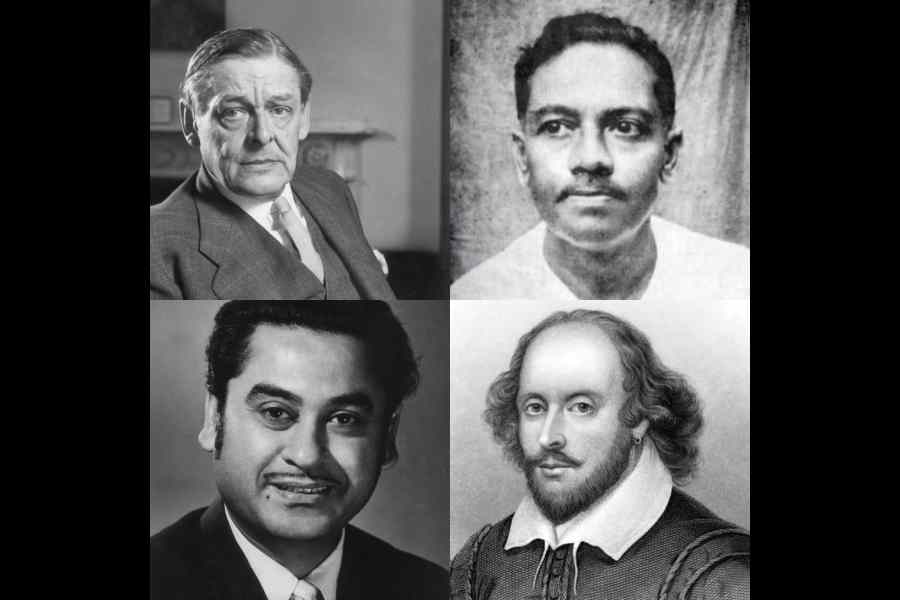

Aided by a remarkable prose that is poetic, analytical and ruminating all at once, Roy interjects her narrative with childhood and adult memories, literary analysis, and life-histories of the provincials, famous and forgotten alike. The list includes Jibanananda Das, William Shakespeare and Kishore Kumar, the famous mofussil private tutors whose pronunciations would probably horrify the posh students of private universities, the boys and girls who were discovering greeting cards in the wake of liberalisation, the two Apus of Bibhutibhushan and Satyajit Ray, and even T.S. Eliot whose attempt to hide his own provinciality was exposed by another provincial, J.M. Coetzee (how do we pronounce his last name, by the way?). Siliguri, the actual place where Roy grew up, often casts its sunlight and shadows on the fictional provincial towns like Madna (English, August) and Malgudi (Swami and Friends). Oxford and Kishorganj become neighbouring villages.

The juxtaposition of characters and places, fiction and non-fiction, plays a crucial role in rescuing the provincials from the linearity of historical progression and complicates the relationship between the vernacular and the metropolitan. The controversy around pronunciation (Roy has a lot to talk about mispronunciations in the book) can be seen as an offshoot of our preference for an easy formula of imbalance of power, which the book challenges quite effectively. Faced with the peculiar predicament of comparing the elitism of French over English with that of an upper-caste scholar over a Dalit student, we must pause and ponder how the provincial ambitions are translated into cosmopolitan desires. It is not an easy task. It needs introspection and empathy. Provincials is a testimony to that.