At the end of some days, Chris Bell just sits and stares at the wall. Like many across the UK, Covid-19 has meant his work has shifted online and now his days consist of video call after video call.

“I’m just completely exhausted,” the faculty officer says. In a week, he can be dialling into as many as 30 different meetings, one after the other. All this, he says, “Can be extremely draining”.

Bell is not alone in finding the new way of working challenging. A recent survey by Actus suggested that nine in 10 UK workers had suffered with so-called “lockdown lethargy”.

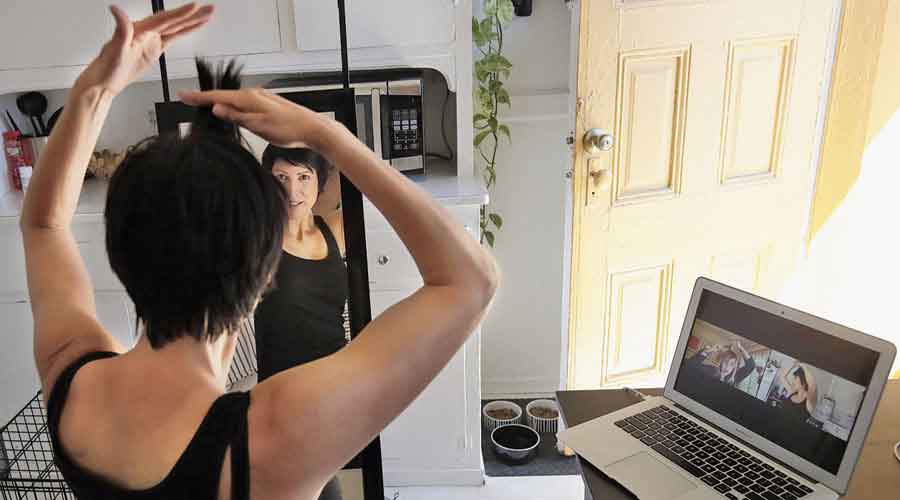

There are scientific reasons for this. “When we’re thinking about video calls, we need to bear in mind that they’re very different from face-to-face interactions,” Dr Daria J Kuss, an associate professor in psychology at Nottingham Trent University, explains.

“You’re missing out on physical cues you would normally have so it takes more cognitive activity to interpret what someone is saying and, in general, you need to be paying more attention.”

Gianpiero Petriglieri, an associate professor of organisational behaviour at Insead, agrees. “There is definitely an element of cognitive overload. When we lose non-verbal signals, we don’t give up on trying to understand other people, so our brain overcompensates.

“It’s like if you know how to drive a motorbike and then you try to drive a car, it’s still driving but it’s not the same.”

It is not just the lack of non-verbal signals that make video calls more tiring. There are practical aspects as well, like the fact there can be no time to reset between calls, people able to click straight from one meeting to the next. Being able to see your own video feed all the time creates additional stress around your reactions, and whether you appear attentive.

“People are actually engaging twice as much as they were before,” says Petriglieri. “The reaction most people have had to the crisis is not to distance themselves, but to double down and make more effort.”

Since the lockdown in March, the number of adults making online video calls has doubled, according to Ofcom. More than seven in 10 people are holding video meetings at least weekly.

Meanwhile, Zoom, one of the leaders in the field, has grown its user base from 659,000 adults in January to 13 million adults in April.

This has meant its share price is now almost 300 per cent higher than it was at the start of the year.

Such companies may be reaping the benefits of workers engaging in more video calls for now, but there could soon come a tipping point. In a bid to curb their “Zoom fatigue”, some are already turning off.

“I’ve cut down on the number of social Zoom calls I’m attending with people, suggesting to meet up in person instead,” Bell says.

This has meant his tiredness has “definitely got better over the past few weeks”.

Tech executives are waking up to this shift. This week, Microsoft released features for its Teams application that it said were geared to make meetings less draining, including “Together” mode, where users’ faces can be cut out and placed in a shared virtual background, such as an auditorium.

The feature will make meetings “more engaging by helping you focus on other people’s faces and body language and making it easier to pick up on the non-verbal cues that are so important to human interaction”, Microsoft says.

Others, such as Zoom and Google, have also been looking at ways of making virtual meetings less stressful, including background noise cancellation tools and options to hide your feed, so you don’t have to see yourself speaking.

Whether these will be enough to keep users on board remains to be seen.

The Daily Telegraph