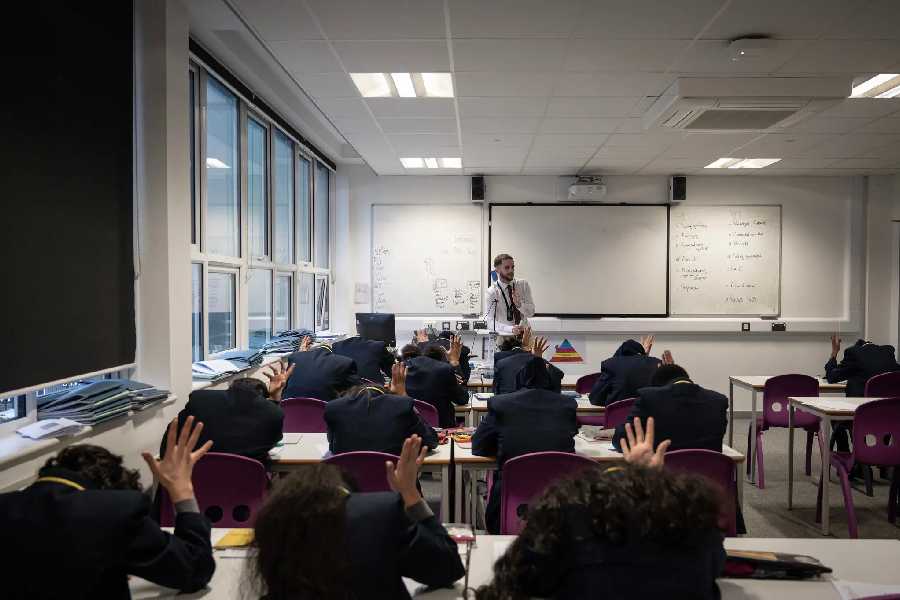

As the teacher started to count down, the students uncrossed their arms and bowed their heads, completing the exercise in a flash.

“Three. Two. One,” the teacher said. Pens across the room went down and all eyes shot back to the teacher. Under a policy called “Slant” (Sit up, Lean forward, Ask and answer questions, Nod your head and Track the speaker) the students, ages 11 and 12, were barred from looking away.

When a digital bell beeped (traditional clocks are “not precise enough,” the principal said) the students walked quickly and silently to the cafeteria in a single line. There they yelled a poem — “Ozymandias,” by Percy Bysshe Shelley — in unison, then ate for 13 minutes as they discussed that day’s mandatory lunch topic: how to survive a superintelligent killer snail.

In the decade since the Michaela Community School opened in northwest London, the publicly funded but independently run secondary school has emerged as a leader of a movement convinced that children from disadvantaged backgrounds need strict discipline, rote learning and controlled environments to succeed.

“How do those who come from poor backgrounds make a success of their lives? Well, they have to work harder,” said the principal, Katharine Birbalsingh, who has a cardboard cutout of Russell Crowe in Gladiator in her office with the quote “Hold the Line.” In her social media profiles, she proclaims herself “Britain’s Strictest Headmistress."

“What you need to do is pull the fence tight,” she added. “Children crave discipline.”

While some critics call Birbalsingh’s model oppressive, her school has the highest rate of academic progress in England, according to a government measure of the improvement pupils make between ages 11 and 16, and its approach is becoming increasingly popular.

In a growing number of schools, days are marked by strict routines and detentions for minor infractions, from forgetting a pencil case to an untidy uniform. Corridors are silent as students are forbidden from speaking to their peers.

Advocates of no-excuses policies in schools, including Michael Gove, an influential secretary of state who previously served as education minister, argue that progressive, child-centered approaches that spread in the 1970s caused a behavioral crisis, reduced learning and hindered social mobility.

Their perspective is tied to a conservative political ideology that emphasizes individual determination, rather than structural elements, as shaping people’s lives. In Britain, politicians from the ruling Conservative Party, which has held power for 14 years, have supported this educational current, borrowing from the techniques of American charter schools and educators who rose to prominence in the late 2000s.

The hard-right firebrand Suella Braverman, a former minister with two Conservative governments, was a director of the Michaela school. Martyn Oliver, the chief executive of a schools group known for its strict approach to discipline, was appointed as the government’s chief inspector for education last fall. Birbalsingh served as the government’s head of social mobility from 2021 until last year, a position she held while running the Michaela school.

Tom Bennett, a government adviser for school behavior, said that sympathetic education ministers had helped this “momentum.”

“There are lots of schools doing this now,” Bennett said. “And they achieve fantastic results.”

Since Rowland Speller became the principal of The Abbey School in the south of England, he has cracked down on misbehavior and introduced formulaic routines, inspired by Michaela’s methods. He said that a regulated environment is reassuring for students who have a volatile home life.

If one student does well, the others clap twice after a teacher says “two claps on the count of two: one, two.”

“We can celebrate lots of children really quickly,” Speller said.

Mouhssin Ismail, another school leader who founded a high performing school in a disadvantaged area of London, posted a picture on social media in November of school corridors with students walking in lines. “You can hear a pin drop during a school’s silent line ups,” he wrote.

The remarks triggered a backlash, with critics likening the pictures to a dystopian science fiction movie.

Birbalsingh argues that wealthy children can afford to waste time at school because “their parents take them to museums and art galleries,” she said, whereas for children from poorer backgrounds, “the only way you’re going to know about some Roman history is if you’re in your school learning.” Accepting the tiniest misbehavior or adapting expectations to students’ circumstances, she said, “means that there is no social mobility for any of these children.”

At her school, many students expressed gratitude when asked about their experience, even praising the detentions they received, and eagerly repeating the school’s mantras about self improvement. The school’s motto is: “Work hard, be kind.”

Leon, 13, said that initially he did not want to go to the school, “but now I am thankful I went because otherwise I wouldn’t be as smart as I am now.”

With around 700 students, Michaela is smaller than the average state-funded secondary, which has around 1,050, according to the government. It is so famous that it attracts about 800 visitors a year, mostly teachers, Birbalsingh said. A leaflet handed to guests asks them not to “demonstrate disbelief to pupils when they say they like their school.”

But some educators have expressed concern about the broader zero-tolerance approach, saying that controlling students’ behavior so minutely might produce excellent academic results but does not foster autonomy or critical thinking. Draconian punishments for minor infractions can also come at a psychological cost, they say.

“It’s like they’ve taken ‘1984’ and read it as a how-to manual as opposed to a satire,” said Phil Beadle, an award-winning British secondary school teacher and author.

To him, free time and discussion are as important to child development as good academic results. He worries that a “cultlike environment that required total compliance” can deprive children of their childhood.

The Michaela school made headlines in January after a Muslim student took it to court over its ban on prayer rituals, arguing that it was discriminatory. Birbalsingh defended the ban on social media, saying it was vital for “a successful learning environment where children of all races and religion can thrive.”

The high court has not yet issued its decision in the case.

Proponents of the strict model and some parents say that children with special education needs thrive in strict, predictable environments, but others saw their children with learning difficulties struggle in these schools.

Sarah Dalton sent her dyslexic 12-year-old son to a strict school with excellent academic results. But his dread of being penalized for minor mistakes created unbearable stress, and he started showing signs of depression.

“There was this fear of being punished,” she said. “His mental health just spiraled.”

When she moved him to a more relaxed school, he started to heal, Dalton said.

In England, government data last year showed that dozens of super strict schools were suspending students at a far higher rate than the national average. (The Michaela school was not among them.)

Lucy Lakin, the principal of Carr Manor Community School in Leeds — which does not follow the zero tolerance model — said that she realized the approach was spreading when a growing number of students enrolled at her school after being expelled. Her school earns high academic scores, but she said that is not the only goal of an education.

“Are you talking about the school’s results being successful, or are you trying to make successful adults?” she asked. “That’s the path you’ve got to pick.”

In the United States, charter schools that adopted similar strict approaches were initially praised for their results. But growing criticism from some parents, teachers and students in the mid-2010s triggered a reckoning in the sector.

The New York Times News Service