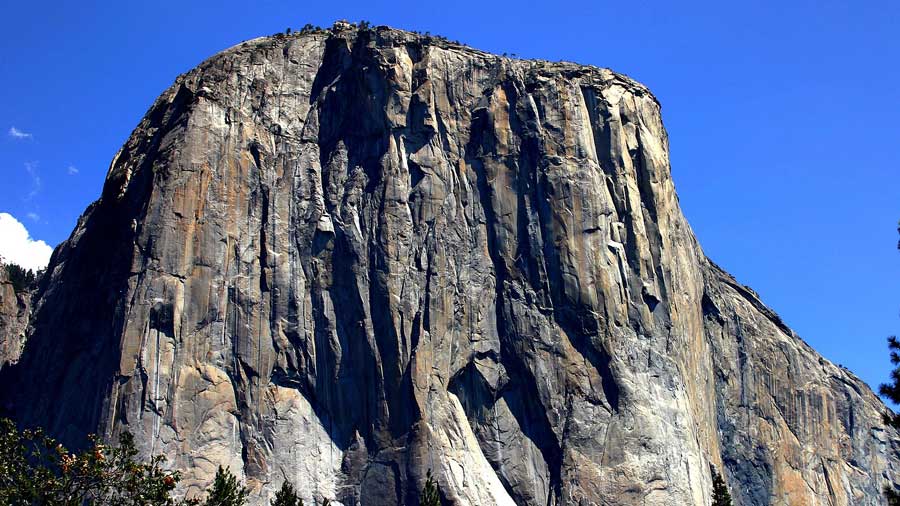

Her head bloodied and bandaged, and her blond hair in a messy bun, Emily Harrington pulled herself over the last lip of El Capitan and into the clear, still night above Yosemite National Park, 21 hours 13 minutes and 51 seconds after she began her ascent.

In her fourth attempt last Wednesday night, Harrington became the fourth person, and the first woman, to scale El Capitan via the Golden Gate route in under 24 hours by free-climbing it — pulling herself upward with her hands and feet and using ropes and other gear only as a safety net.

El Capitan, known as El Cap, is a 3,000-foot-high granite edifice that draws thousands of climbers to Yosemite each year. Climbers typically take around four to six days to reach the top, using a variety of routes. Only a few elite climbers, Harrington now among them, have done it in less than a day.

Harrington, 34, of Tahoe City, California, chose the Golden Gate route, which is divided into 41 pitches, or sections, because she had struggled to complete it in six days when she was first learning to free-climb Yosemite’s monoliths.

During a free-climb ascent, a climber goes up one pitch, then stops and is followed by a belayer, a person attached to the other end of the rope. If the climber falls, she returns to the bottom of the pitch and begins again.

As Harrington climbed, she said, she repeated a mantra: “Slow is smooth, smooth is fast.”

“It was this giant representation of everything I’ve worked for in climbing boiled down into one day,” she said in an interview. “There was a lot going on in my head, but at the same time I had this confidence deep down because I knew that I was more ready than I ever had been in my entire life.”

Harrington, who started at about 1.30am, completed the first two-thirds of the route with Alex Honnold, whose free-solo climb of El Cap, without ropes, was chronicled in the documentary film Free Solo. They were attached by a rope — her on top, him at the bottom — moving up the wall like a caterpillar.

For the last and most difficult third, Harrington’s boyfriend, Adrian Ballinger, a professional guide whom she met atop Mount Everest, swapped in as belay.

The climb went smoothly until she attempted a difficult pitch in the sun around noon on Wednesday. Her fingers were so slick with sweat that she slipped off, she said, so she rested for 30 minutes and tried again. She slipped off again, this time smacking her head against the wall as she swung on the rope. Suddenly, she said, there was “blood everywhere, spewing out from my head”.

She flashed back to a brutal fall she suffered last year while attempting the same climb, one that sent her to a hospital. But after checking her vital signs and bandaging her head, she put her hands on the rock once more.

“There was part of me that wanted to give up and the other part of me was like, ‘You owe it to yourself to try again,’” she said.

“Then I just had one of those attempts where it was an out-of-body experience, like, ‘I can’t believe I’m still holding on, I can’t believe I’m still holding on,’ and then I was finished with the pitch.”

Harrington, who grew up in Colorado, has been climbing since she was 10. She is a five-time sport climbing US national champion and a two-time North American champion. She scaled Mount Everest and Mont Blanc in 2012, and Ama Dablam in 2013.

Free-climbing El Capitan, she said, requires strength, stamina, technical skill and the fitness to endure a day of exertion. The first to climb was Lynn Hill, whose scaling of El Cap in 1994, following the Nose route, remains one of the most famous ascents in rock climbing.

Free-climbing El Cap is still very much “a male-dominated thing, despite the fact that Lynn was the first to do it”, Harrington said. “I always received so much advice from men, people telling me how I should do things, how I’m doing it wrong, but in the end I just decided to do it anyway.”

Steph Davis, who in 2004 became the second woman to free-climb El Capitan in under a day, using the Freerider route, said Harrington had achieved something truly remarkable.

“El Cap is so big that it becomes a really big effort to free it in a day, and it takes a really big commitment and a skill set beyond just the hard climbing it involves,” she said. “I think that’s why there’s a really big time span between seeing people do it.”

A little after 10.30pm, after hours of uncertainty and mental and physical strain, Harrington used her chalk-caked hands to pull herself onto the ledge at the top.

“A lot of times, climbing achievements, you don’t have a stadium, you don’t have a bunch of people watching on live television,” she said. “It was this intimate moment in a really special place.”

New York Times News Service