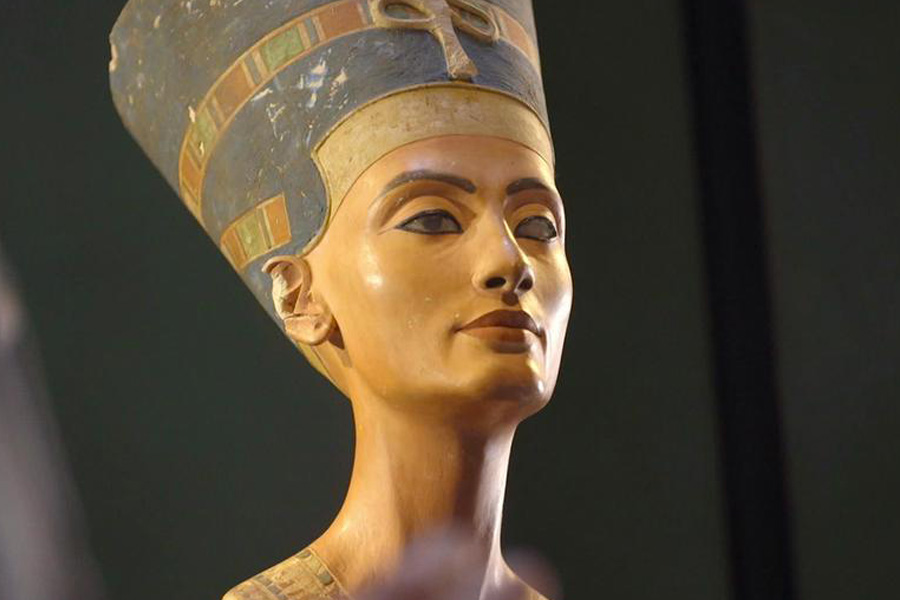

Nefertiti appears to gaze into the distance, proud and aloof. Not much is known about the woman who lived in ancient Egypt around 3,500 years ago. Her name means "the beautiful one has come forth."

But was she tall or short, was she stern, generous, or haughty? All her personal qualities have been lost to history. There are no reports from her contemporaries, no papyrus with stories from her life. Only a few ancient reliefs and inscriptions give scant details about the mysterious Nefertiti.

What is known is that at a young age, presumably between the ages of 12 and 15, she became the wife of Amenhotep IV. He was given the epithet of "heretic pharaoh" because he abolished polytheism and subsequently worshiped only Aten, the god of light, depicted as a radiant sun disk.

He also changed his name, from Amenhotep to Akhenaten ("he who serves Aten"), while Nefertiti became Neferneferuaten ("beautiful is the beauty of Aten"). She bore the title of Great Royal Wife and stood on equal footing with her husband, according to Olivia Zorn, deputy director of the Egyptian Museum Berlin, which is part of the Neues Museum. "They formed a triad, a trinity, with the god Aten. Aten, Akhenaten and Nefertiti were virtually a government unit," she told DW.

A new city for the god Aten

Around 1350 BC, the royal couple left the capital Thebes and within a short time built the city of Akhetaten ("horizon of Aten"), with a population of 50,000, as the new royal residence. The location was a valley protected by steep cliffs, the plain of Amarna.

Akhenaten also had a temple dedicated to his god built in record time, the Gem-pa-Aten ("Aten is found"). But by decreeing monotheism, the ruling couple made powerful enemies. Thousands of priests were unemployed.

Akhenaten died in the 17th year of his reign. No one knows for sure what happened to Nefertiti then. According to one theory, she may have ruled for a time after her husband's death under the name Smenkhkare. "But she may well have died before him," said Olivia Zorn.

'Most vivid Egyptian artwork'

The historical record is more detailed with the next pharaonic dynasty, under the legendary Tutankhamun. He and his advisors resurrected the old gods and had Akhenaten's structures honoring Aten torn down to their foundations and used as quarries. The new capital Akhetaten also crumbled.

We may never have heard of Nefertiti at all if the German architect and Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt hadn't traveled to Egypt in the early 20th century, on the trail of the legendary city of Amarna.

He had been commissioned by Kaiser Wilhelm II to acquire items for the royal museums in Berlin. On December 6, 1912, he and his excavation team came across the workshop of a sculptor, who may have worked for the royal court in the year 1300 BC. There were numerous busts under the mounds of rubble, including one with a dark blue cap crown. The figure's earlobes were pierced, the eyes rimmed with kohl. The iris was missing from the left eye, but otherwise the bust was completely preserved.

Borchardt was thrilled: "We held the most vivid Egyptian artwork in our hands," he noted. "Life-sized painted bust of the queen, 47 cm high. Work quite outstanding. No use describing, must be seen."

Nefertiti's cap crown was a common headdress in ancient Egypt, as were voluminous wigs. The queen's head was most likely shaved — that would have made it easier to wear heavy headdresses, as well as preventing infestations by lice.

Did she also use makeup to enhance her beauty? "Makeup like we have today didn't exist back then," says Zorn. "But people made up their eyes, decorated them with that pretty eyeliner. It also had an antiseptic effect, warding away bacteria that could get into the eyes and lead to blindness."

Exchanged antiquities: Nefertiti for an altarpiece

With the financial support of the German Oriental Society, which funded his Egypt expedition, Borchardt took the bust of Nefertiti to Berlin. According to the regulations of the time, all ancient finds were divided equally between Egypt and the country that carried out the excavations. Borchardt represented the German Empire.

Gaston Maspero, director of the antiquities service under French guardianship, commissioned his colleague Gustave Lefebvre with arranging the division of the find. One part contained, among other things, the bust of Nefertiti, the second an altarpiece showing the royal couple Akhenaten and Nefertiti with three of their children.

Because the Egyptian Museum in Cairo did not yet own an altarpiece, it was decided they would not take the bust. Later, Borchardt was accused of presenting the bust under less-than-ideal conditions, so Lefebvre would not recognize its true value.

Nefertiti conforms to modern beauty standards

So the Egyptian beauty went on a journey to Berlin, where she was first presented to the public in 1924, triggering a veritable Nefertiti craze. Images of the bust were splashed on magazine covers and used in advertising campaigns for cosmetics, perfume and jewelry, as well as beer, coffee, and cigarettes.

Having lain lost in the desert sands for millennia, the bust of Nefertiti became an admired idol — as the real person it was based on presumably was during her lifetime.

"Back in the early 20th century, she already fit today's modern ideal of beauty, with her high cheekbones and delicate features,” said Zorn. But she added that "we of course can't say precisely whether that was also the beauty ideal some 3,500 years ago.”

The secrets of the bust of Nefertiti

The colorful bust is not the only image of Nefertiti that was found. Ancient reliefs show her hand in hand with Akhenaten during religious ceremonies, or as a devoted mother to her six daughters. And there are other statues: "All of them corresponded to the subjective idea of the artist; that is, to what he found beautiful. Or he created what he was told to do by the king or by high officials. But does that really show the real Nefertiti?"

The bust is made of a limestone core, upon which the sculptor applied stucco to model Nefertiti's features.

A computed tomography (CT) scan in 2006 revealed a wrinkled face carved into the limestone. Zorn says, "The artist applied a thin layer of stucco over that, which functioned the way foundation makeup does, and smoothed out the surface."

Nefertiti most likely did have both eyes, but Zorn has a theory about why the famous bust only has one: "It's simply a model. It was used by the artist as a template for other statues of the queen. That one iris insert was probably used to try out different materials," she explains.

The challenge of creating an authentic nose

To get a more accurate reconstruction of Nefertiti's actual face, one would need her mummy. "But so far, Nefertiti's mummy has not been clearly identified, although there have often been attempts," said Zorn. And even if her mummy were to one day be conclusively identified, there would still be inaccuracies. "Mummies are naturally caved in. There are only the bones and the skin, and the difficult part of a facial reconstruction is usually the nose."

Of course, there are scientists who could say exactly how much flesh had been under the skin. "But I think that with what's available to us today, it's not possible to definitively reconstruct a nose. However, you could surely make a Nefertiti out of any mummy, especially since it's likely you'd be influenced by the image of the famous bust when working." That, she adds, would no longer be an objective reconstruction.

Today, some 3,500 years after her death, its impossible to say exactly how she looked. And thanks to the bust, she remains a remarkable beauty in people's minds.

To whom does the bust belong?

Egypt would like to have the country's famous ambassador back, but Berlin sees no reason to return it. "There are absolutely no restitution claims. The legal situation is clear," said the deputy director of the Egyptian Museum — after all, the bust was awarded to the German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt by contract 100 years ago.

But seen from today's perspective, the question arises as to whether Egypt had any say in the matter at all, since the country was under British colonial rule and the antiquities authority was under French management.

Olivia Zorn quickly has a counterargument for keeping it: "The bust is not suitable for travel, if only for conservation reasons. If we send it on a journey, we run the risk that it will not arrive intact. And I don't think anyone wants that."

So Nefertiti will most likely continue to hold court in Berlin for the time being.