With only 50 days until the deadline for Britain to leave the European Union, the political negotiations for a withdrawal agreement remain stuck — and the economic concerns are growing.

By most accounts, Britain’s economy would be hammered if it crashed out of the European Union without a deal. The gloomiest projections show that Britain would lose 9.3 per cent of its gross domestic product, housing prices could sink by 30 per cent and the pound could fall to $1.10 against the dollar. (The pound, seen as a barometer of confidence in Brexit, is now at about $1.29.)

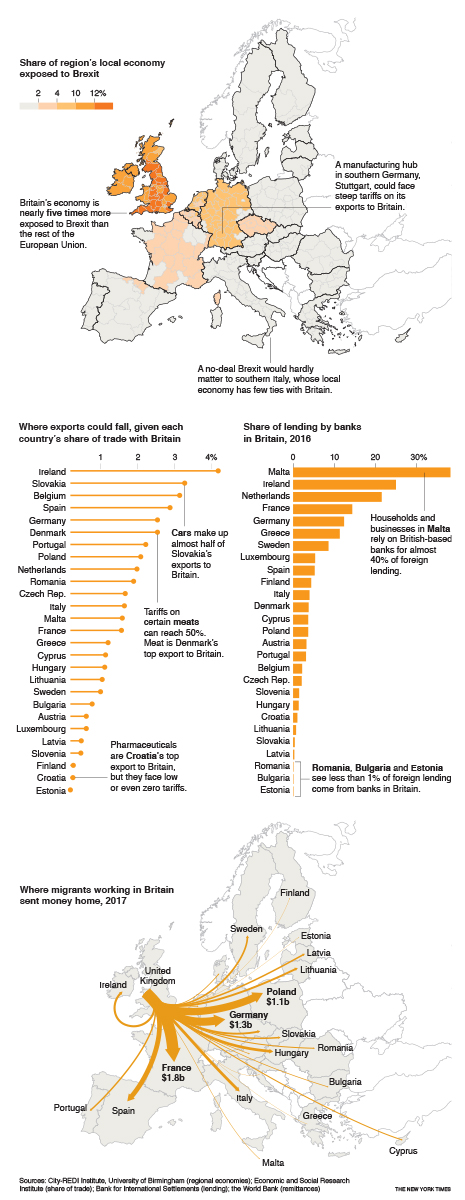

But the impact would also be painful for the 27 remaining member states in the European Union. Even though the bloc is a single market, each country has a unique relationship with Britain as far as the movement of goods, services, people and capital.

The regions most exposed to a no-deal Brexit would experience issues like disruptions in trade, costly tariffs, fragmented supply chains and restrictions on services.

In the political negotiations, the Europeans have the stronger position. But experts agree that hardly anyone wins if a withdrawal deal isn’t struck — and some countries could lose quite badly.

No more free trade

The immediate risk of a no-deal exit is that it would leave Britain and the European Union without a trade agreement, forcing them to default to the tariffs set by the World Trade Organisation.

Any price increases from tariffs are likely to be absorbed by consumers, and for some goods — meat, dairy and tobacco products — tariffs are upward of 15 per cent.

One study looking at the impact on trade of a no-deal Brexit found a wide range of exposure across Europe, but with every member of the bloc facing a possible reduction in trade.

Ireland is the most exposed to tariffs and changes in trade. Nearly 14 per cent of its exports go directly to Britain, and a majority of its trade passes through the country at some point. In addition, two of its top exports — meat and dairy products — face some of the highest tariffs.

Germany exports a wide variety of industrial products to Britain, including almost 800,000 cars a year — or about 14 percent of all the cars it makes domestically.

The Netherlands’ trade with Britain is significant but partly inflated by the so-called Rotterdam effect — goods flowing through the country’s large port, though they may originate (or are destined for) other locations.

European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker prepares to shake hands with British Prime Minister Theresa May before their meeting at the European Commission headquarters in Brussels on Thursday, February 7, 2019. AP

European workers in Britain

Theresa May has assured those already living or working in Britain that they will be able to remain in the country legally, but in the event of no deal, restrictions or requirements for new migrants could come sooner than planned.

This could affect EU countries that rely on workers abroad to send money home. Britain is the third-largest remittance-sending country in the European Union; in 2017, migrants from the bloc sent home about $9 billion.

There are almost 1 million people from Poland living and working in Britain, and it’s one of the largest recipients of remittances. Polish migrants working there sent home more than $1 billion in 2017; so did migrants from France and Germany working in Britain.

In Hungary, government officials have said they hope migrants will return home to work.

Lithuania has the largest percentage of its population living abroad in Britain — nearly 8 percent — many of whom came over in 2004 after the country joined the European Union.

Financial centre fragments

With the most developed financial centre in the European Union, Britain is relied upon for services including lending, currency trading, insurance contracts and asset management.

Financial firms have been busy setting up legal entities in the European Union so that they can continue to provide these services even after Brexit. And British lawmakers, aware that Britain’s clout as a financial hub and gateway could be at risk, have tried to mitigate the effects of the country leaving with no deal: a temporary permissions regime that will give EU firms access to the British market and a deal with Switzerland giving over continued access to each other’s insurance markets.

The European Union has also passed regulation that will allow certain activities like the clearing of derivatives to continue for a limited time.

But these measures are unlikely to make up for the loss of so-called passporting rights, which allow institutions based in Britain to offer a huge array of financial services.

Banks in Britain, for example, play an important role in lending across the entire bloc. Borrowing from these banks could be limited or become more expensive after Brexit because it’ll cost more to route through Britain without passporting.

But Britain’s departure could also prove beneficial to the EU countries that succeed in bringing home some firms currently based in Britain. The cost of setting up shop in new locations and the eventual loss of efficiency, however, are expected to outweigh the gains from relocations and could push up the cost of financial services in the long run, say analysts at PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Cities like Dublin, Paris, Amsterdam and Frankfurt, Germany, will benefit from the thousands of jobs that are expected to shift from Britain. Germany and Ireland have been popular for activities like banking, while Luxembourg has attracted asset managers.

c.2019 New York Times News Service