Shortly after former Vice-President Joseph. R. Biden Jr selected Senator Kamala Harris of California as his running mate, Neil Makhija’s father sent him a photo.

It was of Harris, sitting with her family in traditional Indian dress, a bindi on her forehead and a raspberry-coloured sari wrapped around her. The image could have come from his own family album, he said, and made clear that for the first time, a candidate for one of US’s highest offices looked like him.

“Spending time in India, growing up where nobody in our neighbourhood really understood us — or maybe they kind of noticed my mother’s accent, or didn’t take her as seriously — those are experiences that Kamala Harris understands,” said Makhija, now the executive director of the Indian American Impact Fund.

“I think we’re feeling seen for the first time,” he added.

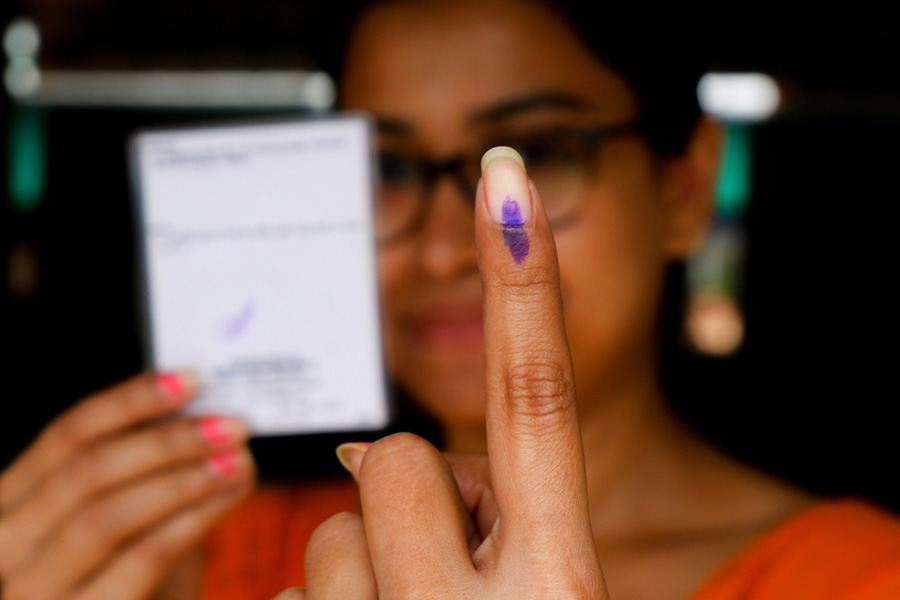

On Tuesday, upon being named Biden’s vice-presidential pick, Harris became the first black woman on a major party’s presidential ticket. She also became the first Indian-American, South Asian and Asian-American person to be chosen — historic firsts in their own right that many Asian-Americans celebrated.

In interviews, Indian-American political leaders and community advocates called Biden’s choice of Harris — the daughter of an Indian mother and a Jamaican father — a refutation of President Trump’s demonisation of immigrants and a powerful statement on American possibility.

“It’s a stand-alone milestone, irrespective of who the opponent is,” said Vanita Gupta, head of the civil rights division of the justice department under former President Barack Obama. “But it is particularly poignant given what this country has endured for the last several years, with this administration that at every turn has sought to divide us and use racism for political gain.”

Some Indian-Americans said the consideration of Harris for a job no Asian-American has held represented a sort of validation of their own family’s choices to come to America. “It’s a reaffirmation of a decision to undertake something that’s really, really difficult,” said Preet Bharara, the former US attorney for the Southern District of New York who tweeted about his Indian mother being excited to vote for Harris.

Representative Pramila Jayapal, a Democrat of Washington state who in 2017 became the first Indian-American woman to join the House just as Harris became the first Indian-American woman to join the Senate, said her mother had sent an elated text message from Bangalore upon hearing the news of Biden’s pick.

“I think it’s a joy about individual accomplishment which travels — believe me — across the world,” she said. “It’s also about the changing landscape and what becomes possible for so many other people when they see barriers being broken.”

Throughout her career and as a presidential candidate herself, Harris has at times described herself simply as “a proud American,” choosing not to call attention to her race or ethnicity, while also imploring the public and the media to stop “seeing issues and people through a plate-glass window as though we were one-dimensional.”

But she has also written about the influence her immigrant mother and Indian grandparents had on her. In her memoir, Harris detailed how her mother, who grew up in southern India, had chosen to come to the US to pursue a doctoral degree at the University of California, Berkeley and eventually become a breast cancer researcher.

She recalled that her grandmother had been a skilled organiser, and her grandfather a part of the movement to win India’s independence. On the campaign trail, as Harris repeated those stories — and cooked Masala Dosa with Mindy Kaling on video — Indian-American activists said more South Asians had become aware of her heritage and had begun to identify with her story.

New York Times News Service