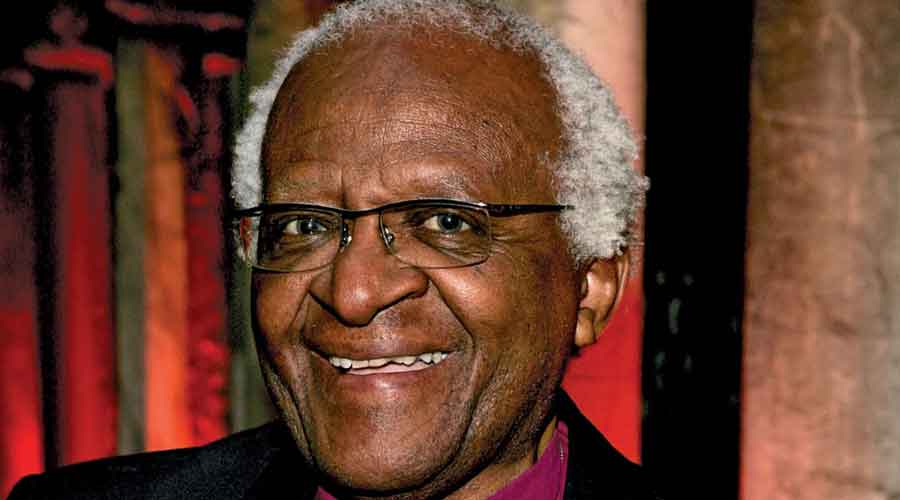

Desmond M. Tutu, the cleric who used his pulpit and spirited oratory to help bring down apartheid in South Africa and then became the leading advocate of peaceful reconciliation under Black majority rule, died on Sunday in Cape Town. He was 90.

His death was confirmed by the office of South Africa’s President, Cyril Ramaphosa, who called the archbishop “a leader of principle and pragmatism who gave meaning to the biblical insight that faith without works is dead”.

As leader of the South African Council of Churches and later as Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, Archbishop Tutu led the church to the forefront of Black South Africans’ decades-long struggle for freedom. His voice was a powerful force for non-violence in the anti-apartheid movement, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

When that movement triumphed in the early 1990s, he prodded the country towards a new relationship between its white and Black citizens, and, as chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he gathered testimony documenting the viciousness of apartheid.

“You are overwhelmed by the extent of evil,” he said. But, he added, it was necessary to open the wound to cleanse it. In return for an honest accounting of past crimes, the committee offered amnesty, establishing what Archbishop Tutu called the principle of restorative — rather than retributive — justice.

His credibility was crucial to the commission’s efforts to get former members of the South African security forces and former guerrilla fighters to cooperate with the inquiry.

Archbishop Tutu preached that the policy of apartheid was as dehumanising to the oppressors as it was to the oppressed. At home, he stood against looming violence and sought to bridge the chasm between Black and white; abroad he urged economic sanctions against the South African government to force a change of policy.

But as much as he had inveighed against the apartheid-era leadership, he displayed equal disapproval of leading figures in the dominant African National Congress, which came to power under Nelson Mandela in the first fully democratic elections in 1994.

In 2004, the archbishop accused President Thabo Mbeki, Mandela’s successor, of pursuing policies that enriched a tiny elite while “many, too many, of our people live in gruelling, demeaning, dehumanising poverty”.

“We are sitting on a powder keg,” he said. Although he and Mbeki later reconciled, the archbishop remained unhappy about the state of affairs in his country under its next President, Jacob G. Zuma, who had denied Mbeki another term despite being embroiled in scandal.

“I think we are at a bad place in South Africa,” Archbishop Tutu told The New York Times Magazine in 2010, “and especially when you contrast it with the Mandela era. Many of the things that we dreamed were possible seem to be getting more and more out of reach. We have the most unequal society in the world.”

Then, in 2011, as critics accused the ANC of corruption and mismanagement, Archbishop Tutu again assailed the government, this time in terms that would have once been unimaginable. “This government, our government, is worse than the apartheid government,” he said, “because at least you were expecting it with the apartheid government.”

He added: “Zuma, you and your government don’t represent me. You represent your own interests. I am warning you out of love, one day we will start praying for the defeat of the ANC government. You are disgraceful.”

His words seemed prophetic when, in 2016, an alliance of religious leaders in South Africa joined other critics in urging Zuma to quit. In early 2018, Zuma was ousted after a power struggle with his deputy, Cyril Ramaphosa, who took over the presidency in February that year.

A global celebrity

For much of his life, Archbishop Tutu was a spellbinding preacher. He often descended from the pulpit to embrace his parishioners. Occasionally he would break into a pixie-like dance in the aisles, punctuating his message with the wit and the chuckling that became his hallmark. While assuring his parishioners of God’s love, he exhorted them to follow the path of non-violence in their struggle.

Politics were inherent in his religious teachings. “We had the land, and they had the Bible,” he said in one of his parables. “Then they said, ‘Let us pray,’ and we closed our eyes. When we opened them again, they had the land and we had the Bible. Maybe we got the better end of the deal.”

His moral leadership, combined with his winning effervescence, made him something of a global celebrity. He was photographed at glittering social functions, appeared in documentaries and chatted with talk-show hosts. Even in late 2015, when he seemed debilitated after an on-and-off battle with prostate cancer dating back to 1997, he met with Prince Harry of Britain, who presented him with an honour on behalf of Queen Elizabeth II.

He coined the phrase “rainbow nation” to describe the new South Africa emerging into democracy, and called for vigorous debate among all races.

Archbishop Tutu had always said that he was a priest, not a politician, and that when the real leaders of the movement against apartheid returned from jail or exile he would serve as its chaplain.

While he acknowledged that there was a political role for the church, he prohibited ordained clergy from belonging to any political party.

In 1989, after President F.W. de Klerk had at last started to dismantle apartheid, Archbishop Tutu stepped aside, handing the leadership of the struggle back to Nelson Mandela on his release from prison in 1990.

But Archbishop Tutu did not stay entirely out of the nation’s business. “We’ve struggled to get these guys where they are, and we’re not going to let them fail,” he said. “We didn’t swallow all that tear gas, and be chased around and be sent to jail and into exile and killed, for failure.”

New York Times News Service