Sunday was Venkatraman Ramakrishnan’s last day as president of the Royal Society, a body set up in 1660 that represents the world’s top scientists. Having done the job in an “honorary” capacity for five years, he hopes life will return to normal.

“It won’t involve travelling and schmoozing,” he said. “At heart I’m a scientist.”

A couple of years ago when he published his book Gene Machine: The Race to Decipher the Secrets of the Ribosome, providing an insight into how he got his Nobel Prize for chemistry in 2009, he had jokingly referred to two diseases — pre-Nobelitis (for those who wait in vain for the prize year after year) and post-Nobelitis (evident in laureates who offer their opinions on anything and everything, regardless of their expertise).

Now, he has identified another condition: “Establishmentitis”.

To be sure, “Venki” has very much enjoyed meeting a wide variety of people in his capacity as Royal Society president, including those outside science, but neither the “London establishment” nor the bureaucracy has been for him.

“It’s not me,” he admitted.

Venki has been a member of the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage), where his advice on wearing face coverings in crowded public spaces proved crucial. He has also headed the Royal Society’s multi-disciplinary group, Delve (Data Evaluation and Learning for Viral Epidemics), which gathered evidence on how countries around the world were tackling Covid-19.

Venki had warned the Indian government last December that it was taking a “wrong turn” over its Citizenship Amendment Bill.

As president, he had wanted to deal with some big issues such as the need to have a “broad-based” education, both at school and at university, so that everyone in society had some knowledge of both the sciences and the arts.

“In fact, my entire term has been hijacked by two issues — Brexit and how we deal with Brexit. And the second is the whole pandemic, and what we could provide as a science community to help with the pandemic,” he said.

He is going back to his “day job” at the LMB (Laboratory for Molecular Research) in Cambridge. For the last five years, he felt distracted as his time was split between his home and lab in Cambridge, and the headquarters of the Royal Society in Carlton Gardens, London, where he was given an apartment.

As president, “I tell you I’ve met a lot of interesting people,” he went on. “I’ve also met a lot of self-important people. Why are they important? They are important for being important. You can’t find out exactly what they did that got them to where they are. So I won’t miss that, I can tell you.”

He explained: “I never felt that I fitted in with what I call the London establishment. That’s not my scene. It was a great privilege, and it opened a window into a different world. And I certainly learned a huge amount that I didn’t know about — how things work.

I don’t necessarily agree with a lot of it. But it was very interesting to do for five years, but it’s not my world.”

Venki says he got “a feel for how government views science” and, as president, “how to be that interface between the science community and politicians and government”.

Being the kind of down-to-earth person Venki is, there was little danger that the “glamour” of being Royal Society president would go to his head.

Venki was remarkably candid: “It’s a bit fake, in the sense, a lot of the relations you have when you’re president of the Royal Society are what I call transactional. They’re not interested in you; they’re only interested in you because of the office you hold.

“And there’s a very big difference between that and some lifelong friends you have. You have to never forget that. Sometimes these relationships blossom into real friendships, but mostly not. Mostly, if you didn’t have that office, they wouldn’t give you the time of day. So you just have to not let the appearance of all these social interactions go to your head.

“Fundamentally, because I came from the US, I have more of a ‘Show me what you’ve done recently’ attitude. You should feel pleased about what you’ve done, not about who you are — which comes from what office you hold.”

That he was elected without having establishment connections sent a positive message to wider society, he thinks. “I’m not sure they would do that again — let me just put it that way — elect somebody as president who didn’t have any of this managerial and establishment and leadership experience,” he said.

“That was a bit of a gamble that they took when they elected me. Luckily, the Royal Society is a robust and very long-lived organisation, so nobody can come and wreck it. I suppose you could say the same thing about the US presidency, although Trump seems to have done quite a lot of damage. But at least I hope I didn’t do that sort of damage. But I’m not sure that it’s likely to happen again.”

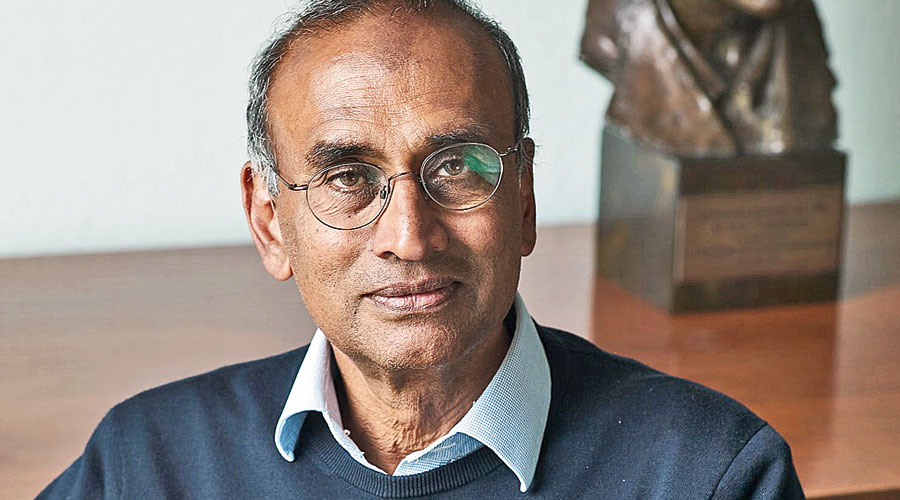

He found a bust of Srinivasa Ramanujan somewhere in the Royal Society building and elevated it to a prominent position behind his desk. Mindful that Ramanujan faced resistance being elected to the Royal Society in 1918, Venki put some effort into promoting the movie on the Indian mathematical genius, The Man Who Knew Infinity, when it was released in 2015. It featured Dev Patel in the lead role.

“That’s such a little thing,” said Venki. “It matters perhaps to people like us who are from India originally. (To us) Ramanujan represents a thing. It’s a moment when Indians suddenly felt, ‘Oh, we’re not inferior, we could actually be just like these colonial masters. We’re just as good if we want to be.’

“And it helped break a psychological barrier among Indians, having people like Ramanujan, or the early physicists, like C.V. Raman and (Satyendra Nath) Bose and (Meghnad) Saha. So in that sense, Ramanujan was a real pioneer. But to the average Fellow, unless they’re mathematicians, it probably doesn’t mean much.”

Venki has found that writing is something he enjoys — and he is getting down to work on his next book, which has the working title Is Death Necessary? Why and How We Age and Die.

Venki, who is 68, set out what he has in mind: “What medicine has done is allow more of us to reach a bigger fraction of our lifespan. So our lifespan is typically 120 years or so. But even if you went back 500 years, there were people who lived to be 100 years. It’s just very few of them reached that stage. But what has not changed is that life span — 120. What’s changed is that instead of living on average for 40 or 45 years, now we’re living to be 80 or 85 or 90 years. But the question of whether we will live past 120 to become, say, 200 years old, is not at all clear.

“My view is that we should not be focused on extending the lifespan. But rather we should be focused on how to make our old age as healthy and productive as possible.”

One thing no one can take away from Venki is that his name will remain forever on the board that lists all those, including Isaac Newton, who have been president of the Royal Society.

A single taxi, with some boxes containing his few belongings — “I hardly had anything there” — sufficed to bring all his stuff back from his flat in the Royal Society HQ to his home in Cambridgeshire.

Venki still cycles everywhere — “I don’t have anything else. That’s my only mode of transportation.”