Scientists warned that the United States someday would become the country hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic. That moment arrived Thursday.

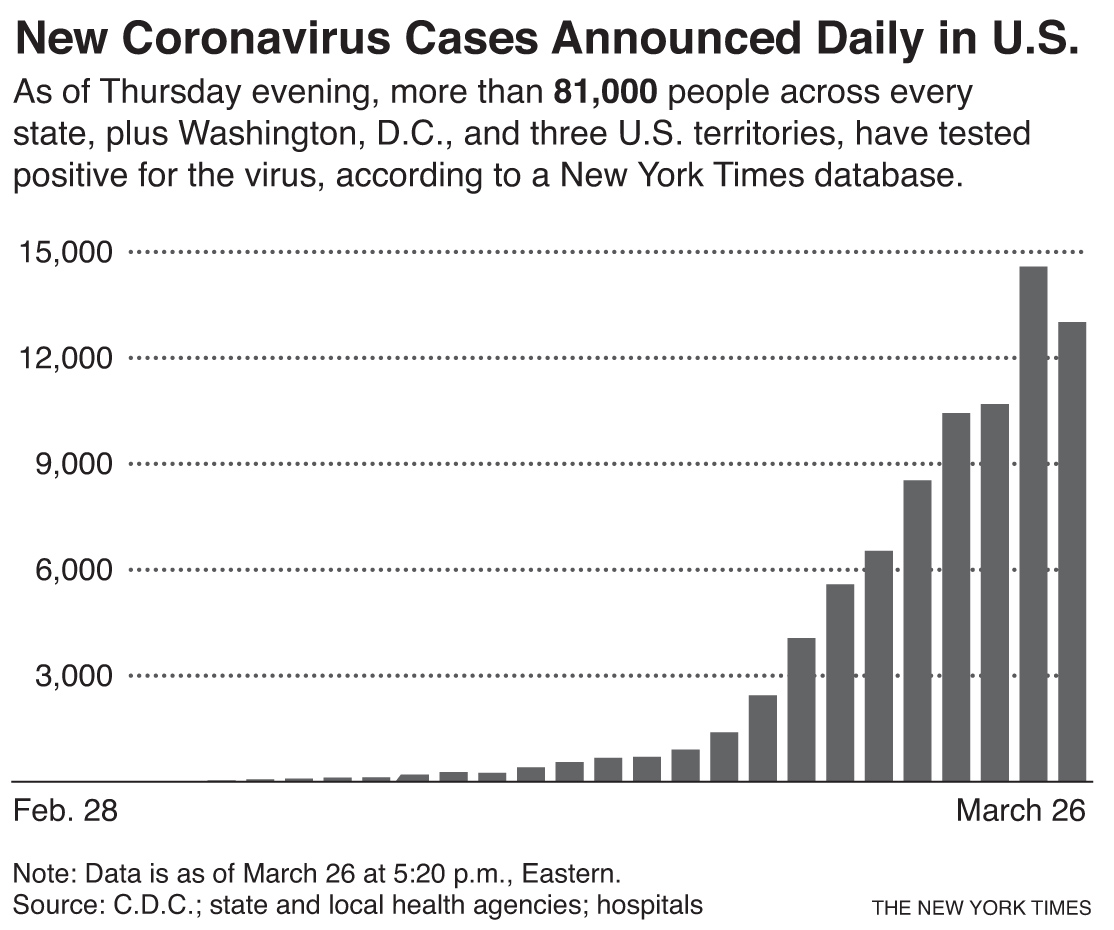

In the United States, at least 81,321 people are known to have been infected with the coronavirus, including more than 1,000 deaths — more cases than China, Italy or any other country has seen, according to data gathered by The New York Times from federal, state and local officials.

With 330 million residents, the United States is the world’s third-most populous nation, meaning it provides a vast pool of people who can potentially get COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

And it is a sprawling, cacophonous democracy, where states set their own policies and President Donald Trump has sent mixed messages about the scale of the danger and how to fight it, ensuring there was no coherent, unified response to a grave public health threat.

At least 81,321 people are known to have been infected with the coronavirus, including more than 1,000 deaths — more cases than China, Italy or any other country has seen, according to data gathered by The New York Times. NYTNS

A series of missteps and lost opportunities dogged the nation’s response.

Among them: a failure to take the pandemic seriously even as it engulfed China, a deeply flawed effort to provide broad testing for the virus that left the country blind to the extent of the crisis, and a dire shortage of masks and protective gear to protect doctors and nurses on the front lines, as well as ventilators to keep the critically ill alive.

“This could have been stopped by implementing testing and surveillance much earlier — for example, when the first imported cases were identified,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at Columbia University in New York.

“If these are the cases we’ve confirmed, how many cases are we still missing?” she added.

China’s leaders, stung by the SARS epidemic in 2003 and several bird flu scares since then, were slow to respond to the outbreak that began in the city of Wuhan, as local officials suppressed news of the outbreak.

But China’s autocratic government acted with ferocious intensity after the belated start, eventually shutting down swaths of the country. Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan quickly began preparing for the worst.

The United States instead remained preoccupied with business as usual. Impeachment. Harvey Weinstein. Brexit and the Oscars.

Only a few virologists recognized the threat for what it was. The virus was not influenza, but it had the hallmarks of the Spanish flu: relatively low lethality, but relentlessly transmissible.

Cellphone videos leaking out of China showed what was happening as it spread in Wuhan: dead bodies on hospital floors, doctors crying in frustration, rows of unattended coffins outside the crematories.

What the cameras missed — in part because Beijing made Western journalists’ lives difficult by withholding visas and imposing quarantines — was the slow, relentless way China’s public health system was hunting down the virus, case by case, cluster by cluster, city by city.

For now, at least, China has contained the coronavirus with draconian measures. But the pathogen had embarked on a Grand Tour of most countries on Earth, with devastating epidemics in Iran, Italy, France. More videos emerged of prostrate victims, exhausted nurses and lines of coffins.

The United States, which should have been ready, was not. This country has an unsurpassed medical system supported by trillions of dollars from insurers, Medicare and Medicaid. Armies of doctors transplant hearts and cure cancer.

The public health system, limping along on local tax receipts, kills mosquitoes and traces the contacts of people with sexually transmitted diseases. It has been outmatched by the pandemic.

There was no Pentagon ready to fight the war on this pandemic, no wartime draft law. There was eventually a White House Coronavirus Task Force, but it has been led by politicians, not medical experts.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is one of the great disease-detective agencies in the world, and its doctors have contributed mightily in skirmishes against Ebola, Zika and any number of other health threats.

But the agency retreated into silence, its director, Dr. Robert Redfield, almost invisible — humbled by a fiasco in the failure to produce basic diagnostic testing.

Now at least 160 million Americans have been ordered to stay home in states from California to New York. Schools are closed, often along with bars, restaurants and many other businesses. Hospitals are coping with soaring numbers of patients in New York City, even as supplies of essential protective gear and equipment dwindle.

Other hospitals, other communities fear what may be coming.

“We are the new global epicenter of the disease,” said Dr. Sara Keller, an infectious disease specialist at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

“Now, all we can do is to slow the transmission as much as possible by hunkering down in our houses while, as a country, we ramp up production of personal protective equipment, materials needed for testing, and ventilators.”

The world will be a different place when the pandemic is over. India may surpass the United States as the country with the most deaths. Like the United States, it, too, is a vast, democracy with deep internal divisions. But its population, 1.3 billion, is far larger, and its people are crowded even more tightly into megacities.

China could still stumble into a new round of contagion as its economy restarts, and be forced to do it all again.

In the meantime, with the virus loose in the streets while millions of Americans huddle indoors, when will it be safe to come out and go back to work?

“The virus will tell us,” said Dr. William Schaffner, a preventive medicine specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical School.

When a baseline of daily testing is established across the country, a drop in the percentage of positive tests will signal that the virus has found as many hosts as it can for the moment, and is beginning to recede.

When hospital admissions have hit a clear peak and begun to plateau, “we can feel optimistic,” Schaffner said. “And when they begin to drop, we can begin to smile.”

That moment may arrive this summer. But as soon as the first of Americans begin venturing cautiously out, we will have to start planning for the second wave.