Battling abdominal sepsis, a 50-year-old woman in a Lucknow hospital was on a ventilator, nearing multi-organ failure. Her doctors had tried several last-resort antibiotics but she had not improved. Then came WCK 5222, a new drug still under evaluation.

The doctors asked India’s apex drug regulatory authorities for permission to use WCK 5222 on the patient on compassionate grounds. She received her first WCK 5222 dose on her 28th day in hospital. Within three days, her condition began to improve. A week later, the doctors discharged her.

Across India, at least 30 critically ill patients infected with multidrug-resistant (MDR) or extreme drug-resistant (XDR) bacteria that don’t respond to even last-line antibiotics — also called superbugs — have returned from the precipice of death after

receiving WCK 5222.

A young patient with multiple infections and wounds and under treatment at the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine, similarly received WCK 5222 leading to the complete healing of the wounds.

WCK 5222 is the outcome of a 27-year research effort by Wockhardt, an Indian pharmaceuticals firm, whose founder Habil Khorakiwala decided in the mid-1990s to begin spending money to discover new antibiotics, defying the convention guiding the country’s domestic pharmaceuticals industry.

The antibiotic — to which Wockhardt has given the brand name Zaynich — is undergoing large-scale clinical trials in India, Europe and North America. If all goes to expectation, the company hopes to launch the product globally in 2026.

“In our war on superbugs, WCK 5222 is set to become a game changer,” Balaji Veeraraghavan, head of microbiology at the Christian Medical College, Vellore, who tests the susceptibility of bacteria to WCK 5222 in the laboratory before any compassionate use of the drug, told The Telegraph.

“I don’t see anything as effective as WCK 5222 coming out from anywhere over the next five or even 10 years. We expect it will save millions of lives.”

Medical experts have estimated that superbugs kill more people in India every year than the country’s official Covid-19 death toll of around 530,000. A study by health researchers at the University of Washington in the US estimated 297,000 deaths directly attributable to and 1,042,000 deaths associated with drug-resistant microbes in India in 2019.

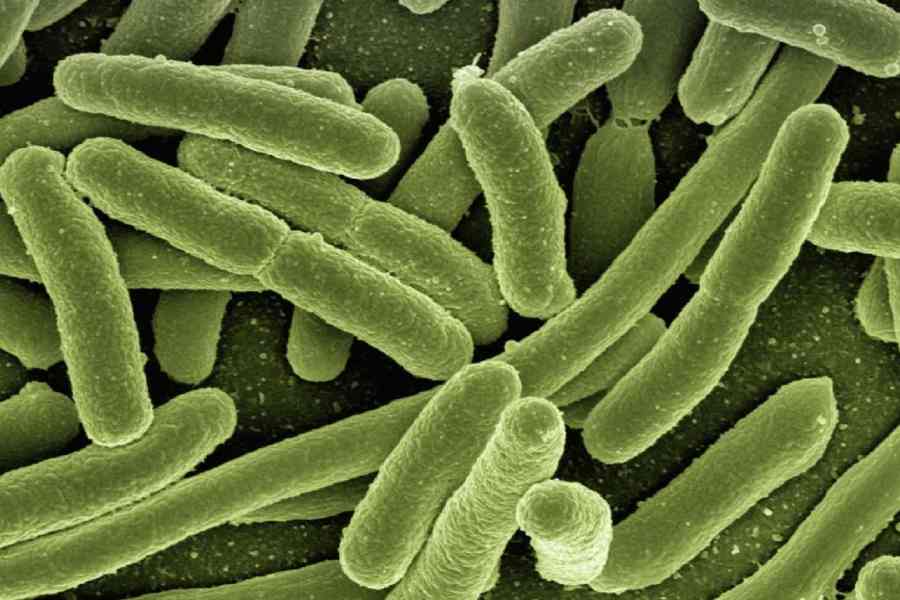

While evolution and genetics nudge bacteria to acquire resistance to antibiotics after prolonged exposure to the drugs, researchers have long flagged concerns that weak government curbs on antibiotic abuse, self-prescription and the lack of personal accountability for doctors for irrational prescriptions have also contributed to resistance.

The biggest killer superbugs in the country are bacteria named Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus, each claiming over 100,000 lives each year. They lead to bloodstream infections, meningitis, pneumonia, urinary tract infections and abdominal infections.

A nationwide survey by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), the country’s apex health research agency, has revealed that 80 per cent of Klebsiella pneumoniae and 91 per cent of Acinetobacter baumannii causing bloodstream infections in 2023 were resistant to a last-resort antibiotic called imipenem. The proportion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to similar last-resort antibiotics rose from 26 per cent in 2017 to 38 per cent in 2023.

Khorakiwala decided in the mid-1990s to focus his company’s drug discovery research efforts on the search for new antibiotics. For India’s pharmaceutical industry, the 1990s marked a decade of transition. India had joined an international trade pact that would introduce patents on drugs in the country instead of only patents on the chemical processes to make drugs.

Until then, India’s drug makers had harnessed innovations in chemistry to overcome process patents. But after the new trade pact, several large companies decided to invest in research aimed at developing new drugs — for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, pain management and infections.

“I think it was a conscious decision by our chairman (Khorakiwala) to only pursue antibiotics. He didn’t want Wockhardt to spread (its) limited resources too thin and too wide. The idea was to gain depth in this research area,” said Sachin Bhagwat, a clinical microbiologist and the chief science officer at Wockhardt who joined the antibiotics discovery unit in 1998.

Bhagwat and his colleagues played molecular jigsaw puzzles with chemical compounds, designing over the years thousands of candidate compounds and screening them for their ability to neutralise MDR or XDR bacteria. They selected WCK 5222 from a pool of 1,500 compounds. Another drug, WCK 4873 — given the alternative generic name of nafithromycin — came from a set of 800 compounds.

Nafithromycin is intended for use in patients with bacterial pneumonia who do not respond to the current treatment, which involves either azithromycin or the combination of amoxicillin and clavulanate potassium. Wockhardt has completed clinical trials and has sought permission from India’s drug regulatory authorities to launch the drug.

“We have already launched two novel antibiotics and have three others under various stages of evaluation,” Bhagwat said. Wockhardt, which company executives estimate has spent $500 million on antibiotics discovery research, had in 2020 launched two new antibiotics for the treatment of MDR Staphylococcusaureus.

Wockhardt isn’t the only drugmaker pursuing homegrown antibiotics.

Chennai-based Orchid Chemicals earlier this year announced the launch of a new antibiotic — a combination of cefepime and enmetazobactam — approved for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections, hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Both these pneumonias are potentially life-threatening.

Bengaluru-based Bugworks Research is collaborating with the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP), an international non-profit, to jointly develop a compound named BWC0977 against MDR bacteria that cause life-threatening infections. GARDP will provide $20 million to Bugworks through technical and financial support while Bugworks has granted GARDP commercialisation rights for BWC0977 in 146 countries.

In lab tests, BWC0977 has shown activity against a range of bacteria that cause pneumonia, bloodstream infections and complicated urinary tract infections.

A pipeline promising new antibiotics from India has been “anticipated and aligns well with India’s growing emphasis on biotechnology and life sciences research as drivers of economic and social progress”, said Rajesh Gokhale, secretary in the department of biotechnology (DBT), which had partially funded nafithromycin’s development.

Gokhale said the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council too was supporting several projects. “These partnerships provide an ecosystem — funding, regulatory guidance, and other support — to de-risk high-potential projects,” Gokhale said.

“We need to leverage such spectacular breakthroughs to boost focus on innovation-driven biotechnology.”

However, doctors and public health experts caution that India will need to strengthen efforts to curb the inappropriate use of antibiotics. “Judicious use of these new antibiotics will be critical for them to remain effective in the long term,” said Polati Vishnu Rao, an infectious diseases consultant at the Apollo Hospital, Hyderabad. Rao and his colleagues have used WCK 5222 to treat a 13-year-old girl who had intractable pneumonia.

One longstanding concern has been the continued sale of some antibiotics without prescriptions and inappropriate prescriptions by doctors themselves. Scientists tracking antimicrobial resistance have long urged hospitals to institutionalise practices that lead to only evidence-based prescriptions.

Kerala banned the sale of antibiotics without prescription earlier this year, leading to a significant drop in antibiotic sales. Two new drugs introduced to treat MDR-TB are not available through retail sales and can be accessed only through the government’s TB programme.

“These examples suggest that mechanisms for restricted access to curb the misuse of medicines meant for serious infections can be established without compromising access to them,” Kamini Walia, head of the antimicrobial resistance studies division at the ICMR, told this newspaper. “This will help preserve the longevity of the new drugs.”