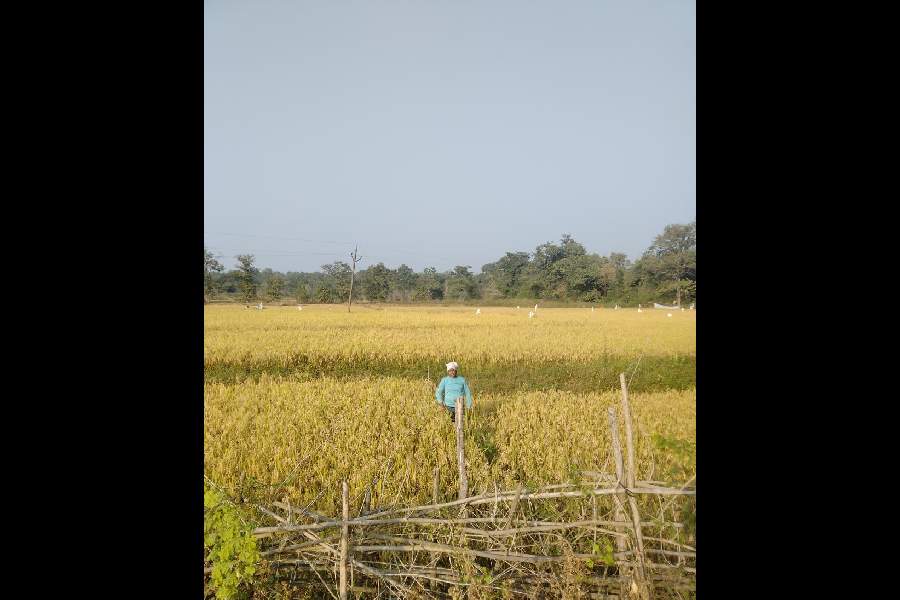

The farmland on both sides of the Chandrapur-Gadchiroli road looks golden with ripe paddy crop waiting to be cut andbundled.

If not harvested within a week, the grains of the Shree 101 paddy variety will start falling and the labour and monetary investment made by Santosh Bhaurao Ghodam, a 35-year-old tribal farmer of Ghanta Chauki village in Chandrapur district of Maharashtra, in the past five months will go waste.

For the past week, he had been looking for labourers but could not find one. On Thursday, Santosh and his wife Babita started cutting the crops, grown on their 1.5-acre plot, themselves.

Labour shortage in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra has left farmers struggling this kharif season. Santosh says agricultural labourers, mainly women workers, are taking part in the campaigning activities of political parties for the Assembly elections, causing the shortage. Added to that is a plethora of government doles that is suspected to have made the low-paying agricultural work even more unattractive.

The pay is higher for a day of campaigning — ₹500 — than a day’s wage for working in the field — ₹400 for men and ₹200 for women.

“Mainly female workers do this work. They are getting ₹500 daily to join campaign rallies and meetings of political parties. We have started cutting the crop. It will take us about a week,” Santosh says.

In the adjacent four-acre plot, Manoj Talande, 30, has grown cotton and paddy over three acres. One acre is vacant. “Because of the labour shortage, I did not grow crops on the entire land. We have grown only as much as our family members can harvest,” Manoj says.

His wife Sima arrives soon after with a large sack full of cotton on her head. “If you look around really hard, you may get labourers from some other villages. But they come and work for four-five hours and ask for a full day’s wage,” Manoj says, adding that Sima has had to work the whole day.

Netaji Subash Chowk in Chandrapur city teems with at least 100 migrant workers at 7am every day, but they come to work in Maharashtraas construction workers. Every second person is from Chhattisgarh.

Santaram Sarwa, who hails from Rajnandgaon district of Chhattisgarh, says he feels more at home in Chandrapur because he has been coming here often for work for decades. “I am a mason. I have never done any agricultural work. I get ₹800 from a day’s construction work. The wage in agriculture is very low. Nobody takes any interest,” Sarwa says.

A male construction worker in Chandrapur earns ₹600 on an average daily while a woman earns ₹500.

Suryakanta Khanke, who has three acres of farmland, says the increase in government “freebies” has affected the availability of workers in Maharashtra.

“The incentive to work and get skills training is gradually declining. When a family gets money under the Ladki Bahin scheme and the PM-Kisan Yojana, free ration every month and many other doles, why should anyone take interest in work? The doles have made people lazy. They prefer to sit at home or work as little as possible,” Khanke says.

He suggests that the government increase the wage rate and stop doles. “People need to be brought back to work. That is not possible without stopping doles,” he says.

Khanke grows paddy but none in the neighbourhood has access to a cutter machine, forcing him to harvest and bundle the crop manually, Khanke says.

“Because of the labour shortage, many patches of farmland here remain uncultivated. In a few years, India will become a food-deficit country,” Khanke says.

Both Santosh and Manoj say earnings from agriculture are low. Ghodamhas spent ₹20,000 on ploughing, sowing and buying fertilisers and herbicides. He will spend another ₹5,000 on thrashing and transporting the grains. The harvest is expected to be 20 quintals. The Union government has fixed a minimum support price (MSP) of ₹2,183 for 1 quintal of common paddy and ₹7,121 for every quintal of middle staple cotton.

“The buyers do not pay the MSP. I will sell paddy at ₹2,000 per quintal. This season my earning will be around ₹15,000. With such a low income, agriculture is not viable. I do a lot of labour work for the forest department to enhance my income,” Santosh says.

Manoj says his income will not cross ₹30,000 this season.

“Many times, the crops get damaged because of heavy rain. We do not get any compensation,” he says.

Srinivas Khandewale, a retired professor of economics at Nagpur University, says that farmers commit suicide because of the meagre income and the burden of loans. He says 550 farmers have committed suicide between January and July 2024 in Vidarbha’s Amravati division comprising Amravati, Yavatmal, Buldhana, Akola and Washim.

Maharashtra votes on November 20