Not since the dark days of the Civil War and its aftermath has Washington seen a day quite like Wednesday.

In a Capitol bristling with heavily armed soldiers and newly installed metal detectors, with the physical wreckage of last week’s siege cleaned up but the emotional and political wreckage still on display, the President of the United States was impeached for trying to topple American democracy.

Somehow, it felt like the preordained coda of a presidency that repeatedly pressed all limits and frayed the bonds of the body politic. With less than a week to go, President Donald Trump’s term is climaxing in violence and recrimination at a time when the country has fractured deeply and lost a sense of itself. Notions of truth and reality have been atomised. Faith in the system has eroded. Anger is the one common ground.

As if it were not enough that Trump became the only President impeached twice or that lawmakers were trying to remove him with days left in his term, Washington devolved into a miasma of suspicion and conflict.

A Democratic member of Congress accused Republican colleagues of helping the mob last week scout the building in advance. Some Republican members sidestepped magnetometers intended to keep guns off the House floor or kept going even after setting them off.

All of which was taking place against the backdrop of a pandemic that, while attention has drifted away, has grown catastrophically worse in the closing weeks of Trump’s presidency. More than 4,400 people in the US died of the coronavirus the day before the House vote, more in one day than were killed at Pearl Harbour or on September 11, 2001.

Historians have struggled to define this moment. They compare it with other periods of enormous challenge like the Great Depression, World War II, the Civil War, the McCarthy era and Watergate. They recall the caning of Charles Sumner (by a pro-slavery Democrat) on the floor of the Senate and the operation to sneak Abraham Lincoln into Washington for his inauguration for fear of an attack.

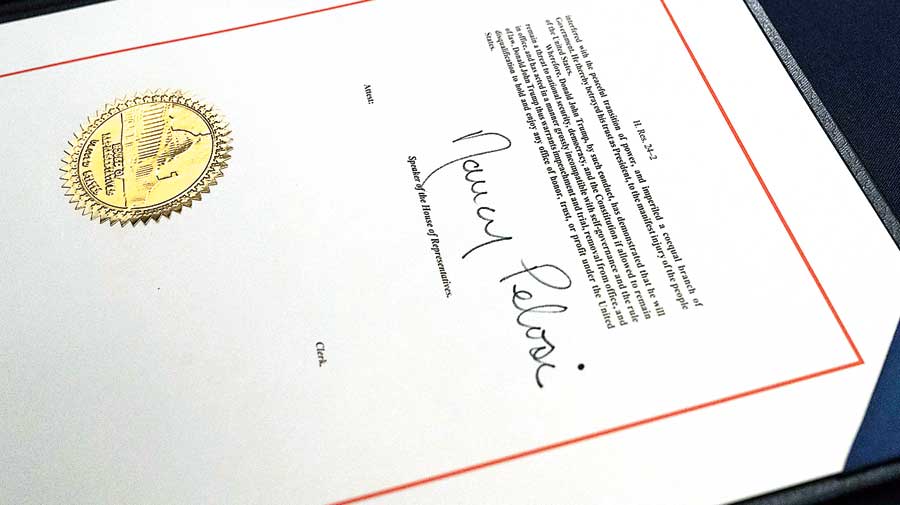

Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s signature on the article of impeachment against President Donald Trump. AP, PTI

They cite the horrific year of 1968 when the Rev. Dr Martin Luther King Jr and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated while campuses and inner cities erupted over the Vietnam War and civil rights. And they think of the wake of the September 11 attacks, when further violent death on a mass scale seemed inevitable. And yet none of them is quite the same.

“I wish I could give you a wise analogy, but I honestly don’t think anything quite like this has happened before,” said Geoffrey C. Ward, one of the most venerable historians in America. “If you’d told me that a President of the United States would have encouraged a delusional mob to march on our Capitol howling for blood, I would have said you were deluded.”

Jay Winik, a prominent chronicler of the Civil War and other periods of strife, likewise said there was no exact analogue. “This is an extraordinary moment, virtually unparalleled in history,” he said. “It’s hard to find another time when the glue that holds us together was coming apart the way it is now.”

All of which leaves the US’ reputation on the world stage at a low ebb, rendering what President Ronald Reagan liked to call the “shining city upon a hill” a scuffed-up case study in the challenges that even a mature democratic power can face.

“The historical moment when we were a model is basically over,” said Timothy Snyder, a Yale historian of authoritarianism. “We now have to earn our credibility again, which might not be such a bad thing.”

At the Capitol on Wednesday, the scene evoked memories of Baghdad’s Green Zone during the Iraq war. Troops were bivouacked in the Capitol for the first time since the Confederates threatened to march across the Potomac.

The outrage over that breach still hung in the air. So did the fear. But the shock had ebbed to some extent and the debate at times felt numbingly familiar. Ten Republicans did vote with the Democrats but most lawmakers quickly retreated back to their partisan corners. As Democrats demanded accountability, many Republicans pushed back and assailed them for a rush to judgement without hearings or evidence or even much debate.

The starkly disparate views encapsulated America in the Trump era. At one point, Representative Steny H. Hoyer of Maryland, the Democratic majority leader, expressed exasperation at the other side’s depiction of events. “You’re not living in the same country I am,” he exclaimed.

And on that, at least, everyone could agree.

New York Times News Service