Fears are growing over the safety of roughly 3,400 Afghan U.N. staff members in Afghanistan, especially the women, with some expressing worry that the Taliban and its extremist allies will target them simply because of their foreign affiliation.

Despite the public assurances of Taliban leaders that the United Nations and other international humanitarian groups in Afghanistan can work unimpeded, accounts of threats, coercion and harassment have increased. Some Afghan staff members are in hiding and have expressed fear they could be killed.

A group of U.N. staff unions and associations launched an online petition in recent days requesting that António Guterres, the secretary-general, “take all necessary measures, including evacuation or relocation, in order to ensure the safety and security of all staff, national or international.”

The petition says that the workers’ “lives are now in danger” because of their work for the United Nations. As of Sunday, more than 1,000 signatures were attached.

Stéphane Dujarric, a spokesperson for Guterres, said in an emailed statement Sunday night that “we are acutely aware of the great stress and genuine fears of some staff, particularly those of national colleagues.” The statement said “extensive security measures are in place to safeguard colleagues” and that “emergency protocols and steps” had been taken to protect them and their dependents in Afghanistan, including relocation away from conflict zones.

The United Nations has rejected what critics call its preferential treatment of non-Afghan staff, a majority of them now safely outside of Afghanistan. U.N. officials have said that unlike countries, the United Nations has no power to issue travel visas — a distinction that Dujarric alluded to in his statement. “We need member states to offer immediate help,” he said. “The U.N. urges all countries to be willing to receive Afghans and to refrain from deportations.”

In a further sign of growing anxiety among Afghan U.N. staff members, female officials from at least four U.N. agencies have written a joint letter imploring the Canadian government to expand the scope of special visas it has announced for 20,000 vulnerable women in Afghanistan.

“There is no doubt that we, as U.N. females, are also extremely vulnerable and are under high risk of danger and violence,” read a copy of the letter, seen by The New York Times. “We are in danger from the Taliban side because these are the women who have worked with international partners and colleagues and are considered spies and apostates.”

The letter asked Canada for visas specifically for female U.N. staff.

These women, the letter stated, are equally vulnerable to threats from “various terrorist groups active in the country who will not spare a single opportunity to attack the U.N. staff, particularly females,” if foreign troops withdraw as scheduled on Aug. 31.

Officials at Global Affairs Canada, the country’s Foreign Ministry, referred a request for comment on the letter to a different ministry, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, which did not immediately respond.

The United Nations has an extensive network of operations inside Afghanistan, where a majority of the population urgently needed humanitarian aid well before the Taliban’s seizure of power.

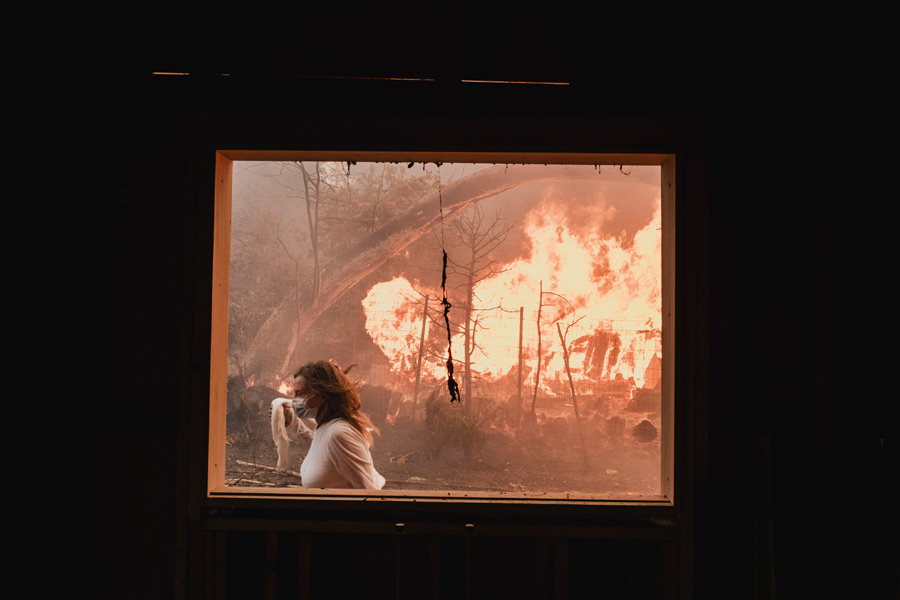

Threats to the United Nations grew last month when its compound in the western city of Herat was attacked. Last week, the organization moved many of the 350 non-Afghan staff in the country to what it described as a temporary relocation in Almaty, Kazakhstan. About 100 of them are believed to still be in Afghanistan.

The fast-moving developments in the Afghanistan crisis have left the United Nations in a basic quandary. Guterres and his aides have repeatedly stressed that the organization remains committed to the humanitarian needs in the country and will maintain a presence there. But it is difficult to answer those needs if its staff members are threatened.

The quandary was underscored Sunday when UNICEF and the World Health Organization said the chaos in Afghanistan since the Taliban seized power a week ago had worsened the humanitarian crisis.

“The abilities to respond to those needs are rapidly declining,” the two U.N. agencies said in a statement. They called for “immediate and unimpeded access to deliver medicines and other lifesaving supplies to millions of people in need of aid, including 300,000 people displaced in the last two months alone.”

New York Times News Service