The fire began with a faulty power strip in a bedroom on the 15th floor of an apartment building in China’s far west. Firefighters spent three hours putting it out — too slow to prevent at least 10 deaths — and what might have remained an isolated accident turned into a tragedy and a political headache for local leaders.

Many people suspected that a Covid lockdown had hampered rescue efforts or trapped victims inside their homes, and though officials denied that had happened, angry comments flooded social media, and residents took to the streets in the city where the fire erupted.

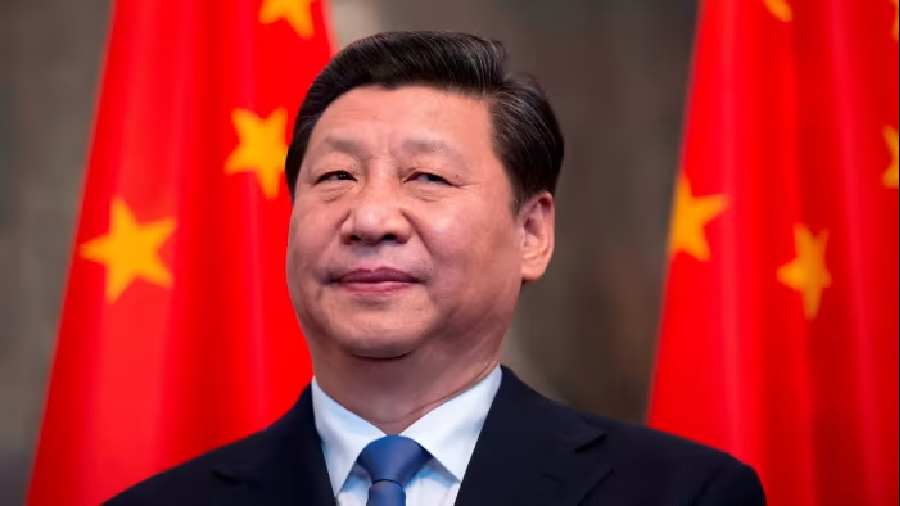

Now the episode in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang region, has unleashed the most defiant eruption of public anger against the ruling Communist Party in years. In cities across China this weekend, thousands gathered with candles and flowers to mourn the fire’s victims. On campuses, students staged vigils, many holding up pieces of blank white paper in mute protest. In Shanghai, some residents even called for the Communist Party and its leader, Xi Jinping, to step down, a rare and bold challenge.

The outpouring has created new pressures on Xi only a month after he secured a third term as party head, sealing his status as China’s most dominant leader in decades. The broader source of ire is his “zero Covid” strategy, which seeks to eliminate infections with lockdowns, quarantines and mass testing. It has kept deaths from the coronavirus much lower than elsewhere but also brought many Chinese cities to a near standstill, disrupted life and travel for hundreds of millions, and forced many small businesses to close.

Protests relatively rare in China

Protests are relatively rare in China. Especially under Xi, the party has eliminated most means for organizing people to take on the government. Dissidents have been imprisoned, social media is heavily censored, and independent groups involved in human rights have been banned. The protests that break out in towns and villages often involve workers, farmers or other locals aggrieved by job losses, land disputes, pollution or other issues that usually remain contained.

But the pervasiveness of China’s Covid restrictions has created a focus for anger that transcends class and geography. Migrant workers struggling with food shortages and joblessness during weekslong lockdowns, university students held on campuses, urban professionals chafing at travel restrictions — the roots of their frustrations are the same.

The Communist Party’s greatest fear would be realized if these similar grievances led protesters from disparate backgrounds to cooperate, in an echo of 1989, when students, workers, small traders and residents found some common cause in the protests demanding democratic change that took over Tiananmen Square. So far, that has not occurred.

About 'pent-up anger'

“Covid Zero produced an unintended consequence, which is putting a huge number of people in the same situation,” said Yasheng Huang, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management who leads its China Lab. “This is a game changer.

“The anger has been pent up for a while, but I think the 20th Congress provided an expectation that it would wind down,” he said, referring to the party’s leadership reshuffle in October. “When that did not happen, the frustration quickly boiled over.”

By Monday morning in Beijing, China’s leaders, including Xi, had yet to comment on the weekend tumult, and party-run news media were also silent.

Covid travel limitations and government restrictions on foreign journalists make reporting on the protests difficult. The New York Times, which has two journalists based in mainland China, has followed the protests online and has reported on the demonstrations through phone interviews, verified videos and sources inside China who have shared their recordings of the events.

Demands against authoritarian system

While many protesters limited their appeals to the loosening of Covid restrictions, some seized the chance to make broader political demands, linking the draconian reach of “zero Covid” to the country’s authoritarian system.

On Sunday, hundreds of students gathered on the campus of Tsinghua University, in northwest Beijing, where they have been largely prohibited from leaving for weeks because of Covid restrictions.

“Democracy and rule of law,” the crowd chanted. “Freedom of expression.”

Later in the day, Tsinghua University announced that it would be offering students free air and rail travel home this week, earlier than usual before the Lunar New Year break.

Candle light vigil

Near Liangma River in Beijing on Sunday night, at least 100 people gathered to light candles and hold up sheets of white paper, an implicit protest of censorship. . The crowd shouted encouragement to the protesters in Shanghai. Others stood on a bridge, also holding up white sheets of paper, while passing drivers honked their horns.

“We don’t want lies; we want respect!” a woman yelled. “We don’t want a leader; we want a voting ballot,” she said in a reference to Xi.

Other footage showed hundreds of people marching down a nearby street, chanting that they wanted freedom, not constant Covid tests.

In Wuhan, the central Chinese city where the pandemic originated in late 2019, hundreds walked along the streets, some pulling down barriers that had been put up to enforce neighborhood lockdowns.

Xi has no easy response

The protests followed hopes that Covid restrictions would gradually ease after officials in Beijing released a 20-point plan this month to limit the scope of pandemic measures. Based on that plan, people had expected local governments to scale back contact tracing and mass quarantines, but when Covid cases surged, officials revived the same sweeping tactics.

Xi has no easy response to the widespread anger. Censors have moved quickly to scrub photos and video footage of the protests. If Xi cracks down on demonstrators, he could anger the public further, straining even China’s formidable security apparatus. If he abruptly lifts many restrictions, he risks hurting his image of unassailable authority that he has built in part on his success battling Covid. The ensuing rise in infections, potentially deadly among the vulnerable, may also become another source of discontent.

“The immediate challenge is whether and how they’re going to continue with ‘zero Covid’ when there is so much frustration. This is a decision he has to make in the next, say, 48 to 72 hours,” Minxin Pei, a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College who studies Chinese politics, said in an interview. “You can arrest people and put them in jail, but the virus will still be there. There are simply no easy answers for him, only hard choices.”

'We want freedom'

The political stakes were made stark in Shanghai on Saturday evening, when what started out as a vigil escalated into a street protest.

Dozens of people had gathered on Urumqi Road, named after the city in Xinjiang, to grieve the victims of the fire. As the crowd grew into the hundreds, chants broke out, with people calling for an easing of the Covid controls. “We want freedom,” they said. A small number of them openly denounced Xi and the Communist Party.

“Xi Jinping!” a man in the crowd repeatedly shouted. “Step down!” some chanted in response.

“This is unheard of in this era,” Pei said. “It reflects a great deal of frustration with the Covid policies. People are just tired.”

The Chinese government is likely to worry that images and video of the protests in Shanghai will spread, despite online censorship, inspiring more unrest. A BBC reporter, Ed Lawrence, was arrested by police during the protests. In a statement, the BBC said later, “During his arrest, he was beaten and kicked by the police” before being released. It was not clear if he was charged. The British broadcaster said officials explained he had been arrested “for his own good in case he caught Covid from the crowd.”

“We do not consider this a credible explanation,” the BBC said.

'Freedom of the press'

Crowds also congregated in Chengdu, a city in southwest China, video from Sunday showed, with some shouting, “We want freedom, we want democracy.” Others yelled, “Freedom of speech, freedom of the press!”

May Hu, who lives in southern Hunan province, said she spent hours watching a livestream of the Shanghai protests on Instagram, which is blocked in China unless using software to surmount censorship barriers.

“Before, everyone only thought about how to escape this all,” said Hu, who is in her 20s. “After, many people’s thinking has changed to, ‘We need to go fight and win freedom.'”

The New York Times News Service