Salman Rushdie has confronted a digitally created version of the man who stabbed him in a BBC documentary about the attack.

The author holds an imagined conversation with Hadi Matar, who is currently in custody charged with attempting to murder Rushdie on stage in 2022.

He has written lines for Matar, included in his new memoir, Knife, and put them into the mouth of a digital avatar. The conversation is recreated using a mix of AI and CGI.

The conversation will be shown in Through A Glass Darkly, a documentary to be shown next week on BBC Two.

The programme’s presenter, Alan Yentob, described the scenes as “magical realism that suits the subject”.

Rushdie said he wanted “to imagine the cast of mind which would be willing to drive a blade into an old man’s neck”.

He told the programme: “I had this idea that I wanted to go and meet him and ask him, ‘Why?’ And then I thought, well, that’s not going to happen.

“First of all, if I was his lawyer I wouldn’t allow it. And then I thought, you know, I could learn more by making him up than by meeting him. Use your skill. My skill is imagination. Imagine yourself into his head. I’ve had that conversation with him in my head for a year-and-a-half now.

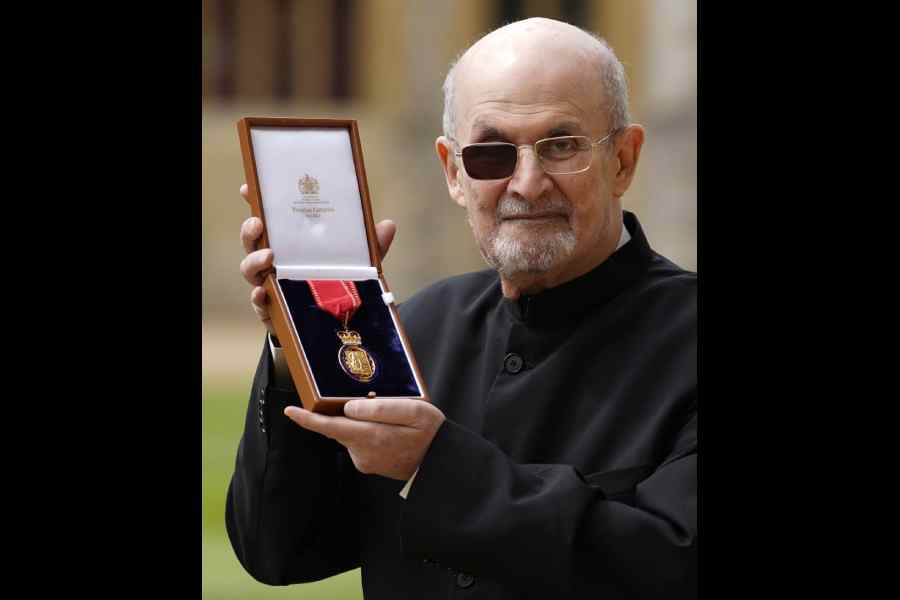

Salman Rushdie. AP/PTI file picture

“A writer’s instinct is to try and make sense of events, and this didn’t seem to really make sense.”

Matar, then 24, attacked Rushdie on stage at a writers’ event in upstate New York in August 2022, stabbing him more than a dozen times. In his only interview since then, Matar told the New York Post he had done it because he deemed Rushdie to be “disingenuous”.

In the imagined conversation, Rushdie asked what he meant by that, to which Matar replies: “It means you pretend to be telling the truth when you’re not.”

Matar calls Rushdie a “devil” and says that they must be destroyed. He claims: “I was ignorant. I was asleep. Now I’m awake. God woke me up.”

In the BBC programme, Rushdie relives the horror of the attack. He was stabbed repeatedly in the face and neck and has lost his eyesight in one eye as a result of his optic nerve being damaged.

“I did wonder if somebody was going to jump out of an audience one day,” he said.

Rushdie added: “Soon after the attack, I heard voices saying I needed my clothes to be cut off me, so they could see where the wounds were. I found myself articulating that my house keys were in that pocket. And I heard somebody say, ‘What does it matter?’

“But, in retrospect, what it says to me is that there was some bit of me that was not intending to die, some bit of me that said ‘I’m going to need those house keys’.”

Rushdie’s wife, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, also spoke about receiving the call telling her that he had been attacked. “I felt like the floor dropped out from beneath me.

“I just started screaming. That was the worst day of my life,” she said.

Last year, Rushdie received the Centenary Courage Award from PEN America, an organisation dedicated to protecting freedom of expression through the advancement of literature and human rights.

In 2015, the award went to Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical magazine which lost 12 staff in an attack by Islamic terrorists.

The magazine had published cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed.

A number of prominent writers protested about the award, but Rushdie told Yentob: “If we can’t defend and honour our colleagues in the media who were murdered for drawing cartoons, then what are we doing? We may as well go home.”

The Daily Telegraph, London