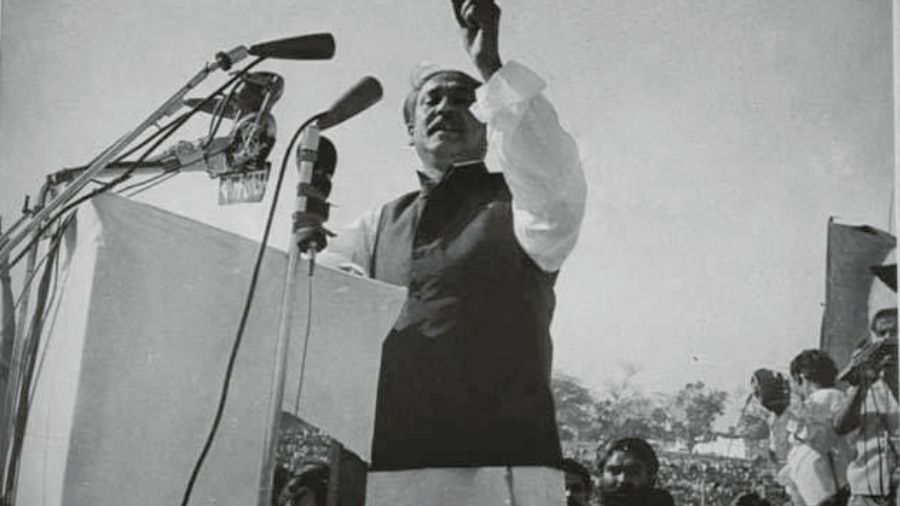

Bangabandhu elevated “democracy” and “secularism” as the distinguishing features of the newly liberated country’s nationhood. Bangladeshis had spent most of the previous 25 years under military dictatorships that, after grossly discriminating against them and exploiting their resources in the name of “Islamic solidarity”, had, at the end, viciously unleashed brutal violence on ordinary people in the street and in their homes. There was, therefore, widespread welcome accorded to constitutional democracy. That welcome did not, however, extend to forging a broad consensus on the desired system of governance. Unbridled political partisanship signposted the emergence of the ‘Argumentative Bangali’ who has ever since converted Bangladesh into a giant adda. “Politics has been much too partisan” and “party politics have so intensified as to reduce all debate to narrow political lines”.

Mujib tried to promote some order and structured discourse through BKSAL, the Bangladesh Krishak Shramik Awami League (Bangladesh Peasants, Workers, People’s party) where the party itself would put up four candidates who would campaign against each other, thus affording real choice to the voter without undermining governance itself. But this experiment came a cropper and probably contributed in substantial measure to the murder of Bangabandhu and his family and the takeover of the reins of government by the army for a quarter of a century from 1975 to 1990, led successively by Generals Ziaur Rahman and Muhammad Hussain Ershad.

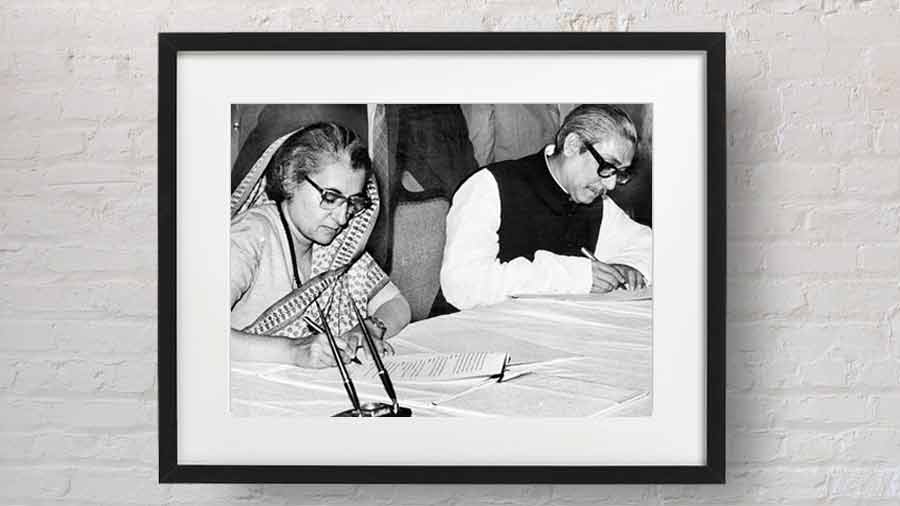

Elections of a sort followed. In 1996, the year of the Silver Jubilee of Liberation, Sheikh Hasina joined the coalition government but played a muted role. It was only in 2009 that she emerged as Head of her own single-party government. She has never since looked back and most Bangladeshi experts are confident that she will overtake Indira Gandhi’s record of 18 years as PM. This has imparted a certain stability to government and afforded the country the opportunity of undertaking its “economic miracle” – but at a price in “authoritarianism” that detracts from its democratic credentials.

The Republic Day parade in Bangladesh. File picture

There is little or no prospect of any Opposition party or parties getting elected at the next round. (Sounds familiar?) Thus, a fourth successive victory is assured, following her victory in 2008-09 in a “free and fair” election, followed by an uncontested “walkover” in her second try, and blatant, if wholly unnecessary, rigging in the third (“unnecessary” because she would have won anyway). This has bred a smugness on the part of the government that allows for “endemic corruption”, the “weakening of institutions”, and the “shutting down of the democratic process itself”, which is how a sympathetic supporter of the Hasina regime described it. But while civil and human rights have been encroached upon, sometimes egregiously, and, said another source, a “climate of fear” has been engendered, the outcome has been very much like Lee Kwan Yew’s Singapore: unprecedented economic growth fostered by authoritarianism. We will be describing this economic miracle in detail in a subsequent part of this series, but it needs to be recognized that any political instability at this stage would “seriously jeopardize” the remarkable record of social and economic development in the Hasina era. Moreover, “terrorism” has been effectively controlled and both “extreme communalism” and the army kept at bay. This is no small achievement and must be chalked up to Sheikh Hasina’s credit. As yet another reflective thinker put it, “She has proved herself a far more astute politician than her father”.

The critique, however, is both trenchant and unsparing. I inform one gathering that when we called on the Prime Minister, my wife, Suneet, had remarked to the PM that the principal difference she had noted between the cross-section of people we had met in Dhaka and a similar cross-section in India is that here in Bangladesh, there is optimism in the air, a sense of having succeeded against all odds and hope for the future, while in India there is despair and despondency, apprehension and uncertainty. “That,” remarks one interlocutor, “is on account of the people you have not met!” Another, while finding Suneet’s comment “encouraging”, suggests we compare “where we have come” with “where we might have reached”. She senses “concern” in the younger generation, but says the concern is “muted” because “platforms where these concerns used to be raised are now under threat”.

I refer to a prominent spokesman of the regime saying I will hear a lot of comment on the regime’s alleged “gagging” of the press. His antidote is to “just read the papers to discover how fiercely critical they are.” A feisty young TV reporter answers this line of argument. She says she can’t find journalists for her programme ready to speak up because they are “terrified of being tripped up”. She underlines that there have been no hard-hitting political cartoons published since 2013 (the last year of Hasina’s first term).

Sheikh Hasina. The Telegraph

Another journalist intervenes forcefully: “There is no reason for hope. We are living effectively in a dictatorship. Freedom of speech is in doubt; the judiciary is broken; education, especially in rural areas, has sadly deteriorated. We. live in a climate of fear.” A social worker rejects such a view as too extreme. The Prime Minister, he says, is “switched on” and a “good implementer.” Contrasting the Khaleda and Hasina regimes, he says, “Then, we had corruption and incompetence; now we have corruption and competence”. He sees the challenge to the nation in other terms. As there is “no end in sight” to “rule by the Awami League”, he sees in governing circles a creeping “sense of invincibility”, a “lack of accountability to anyone”, “no appetite for outside advice”, and “continuous self-adulation”. Access to the Prime Minister, he concludes, “is the crux of the governance system”. So, businessmen are compelled to spend their time lobbying. Hence, how long will this go on is the question on everyone’s mind. The answer lies in “proper elections” and “more democracy”.

While endorsing the need for “proper elections” and “more democracy”, others see little hope of this sensible course being adopted as the accent in governance is most on the Rapid Action Battalion’s forced “disappearances” and “extra-judicial killings”. The space for free and fearless comment is being “denied to us” and media owners are being kept on a short lease by being denied government advertisements, a major source of revenue, if their journals or TV comment goes too far out of line. The Digital Security Act has sounded the “death knell” of investigative journalism and those resorting to the Right to Information provisions of the law are persecuted. The sedition law hangs like a sword of Damocles over citizens. (Does that also not sound familiar?)

Another participant comes down heavily on the judiciary as “one of the weakest institutions”, she claims, “because it is completely politicized” by judicial appointments falling “in the executive realm”. This makes elevation to the bench and further promotions dependent not on “seniority or experience or ability” but on “loyalty” to the regime. She alleges that there is “pervasive fear” among judges, so much so that instances of judges asking lawyers not to represent certain clients are not unknown. The example is cited of former Chief Justice Surendra Kumar Sinha who, it is said, has been hounded into exile in Canada because some of his judicial pronouncements annoyed those in authority. Also, it is alleged, there is “judicial financial corruption at the highest levels”. Compounding the virtual absence of an independent judiciary, gross abuses of human rights violations go uninvestigated and unpunished, especially as there is a lack of access to justice. “Denial of democracy leads to denial of justice,” is a constant refrain. The road to economic power runs clearly through the exercise of political power. It results in “rigging on a grand scale” by local candidates. And this in turn makes for a strong nexus between politics and business. “We are barely a democracy,” complains one intellectual at another get-together who has been specially called to meet me ‘so I get the other side of the picture’. “We have,” he continues, “sham elections, arbitrary government and a corrupt, overweening bureaucracy.”

The younger element does not appear to share the fury or the anger of the older lot. One says this because the youth are no longer looking to Government to solve their problems. They prefer relying on themselves. Another says she is a “realist” but also an “optimist”. After all, she says, we are still a “young country” and “Liberation has liberated our minds”. She points with pride to the story of microfinance and the performance of the private sector, and the State having risen successfully to the challenge of Covid-19.

The last word rests I believe with a sympathizer of the regime who readily admits the last elections were rigged and the dire consequences that have befallen the nation, with some 70% of MPs being businessmen and the Cabinet packed with tycoons. The “litmus test”, therefore, of whether Bangladesh remains a democracy will be the “next general elections”. He is convinced they will be free and fair and confer on the next government “legitimacy in the eyes of the people”.

Tomorrow: Bangladesh secularism@50