Robert Mugabe, the first prime minister and later president of independent Zimbabwe, who traded the mantle of liberator for the armor of a tyrant and presided over the decline of one of Africa’s most prosperous lands, died on Friday. He was 95.

The death was announced by his successor, President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

“It is with the utmost sadness that I announce the passing on of Zimbabwe’s founding father and former President, Cde Robert Mugabe,” he wrote on Twitter on Friday, using the abbreviation for comrade. “Mugabe was an icon of liberation, a pan-Africanist who dedicated his life to the emancipation and empowerment of his people. His contribution to the history of our nation and continent will never be forgotten.”

In August, Mnangagwa had said that Mugabe had spent several months in Singapore getting treatment for an undisclosed illness.

Mugabe, the world’s oldest head of state before his ouster in 2017, was the only leader Zimbabweans had known since independence, in 1980. Like many who liberated their countries, Mugabe believed that Zimbabwe was his to govern until the end. In a speech before the African Union in 2016, he said he would remain at the helm “until God says, ‘Come.’”

Throughout, Mugabe remained inscrutable, some would say conflicted. Remote, calculating, ascetic and cerebral, a self-styled revolutionary inspired by what he once called “Marxist-Leninism-Mao-Tse-tung thought,” he affected a scholarly manner, bespectacled and haughty, a vestige of his early years as a schoolteacher. But his hunger for power was undiluted.

In an interview with state-run television on his 93rd birthday, in February 2017, Mugabe indicated that he would run again in presidential elections in 2018.

“They want me to stand for elections; they want me to stand for elections everywhere in the party,” he said. “The majority of the people feel that there is no replacement, successor, who to them is acceptable, as acceptable as I am.”

He added, “The people, you know, would want to judge everyone else on the basis of President Mugabe as the criteria.”

Events proved him wrong. In November 2017, army officers, fearing that Mugabe would anoint his second wife, Grace Mugabe, as his political heir, moved against him. Within a dramatic few days he was placed under house arrest and forced by his political party, ZANU-PF, to step down.

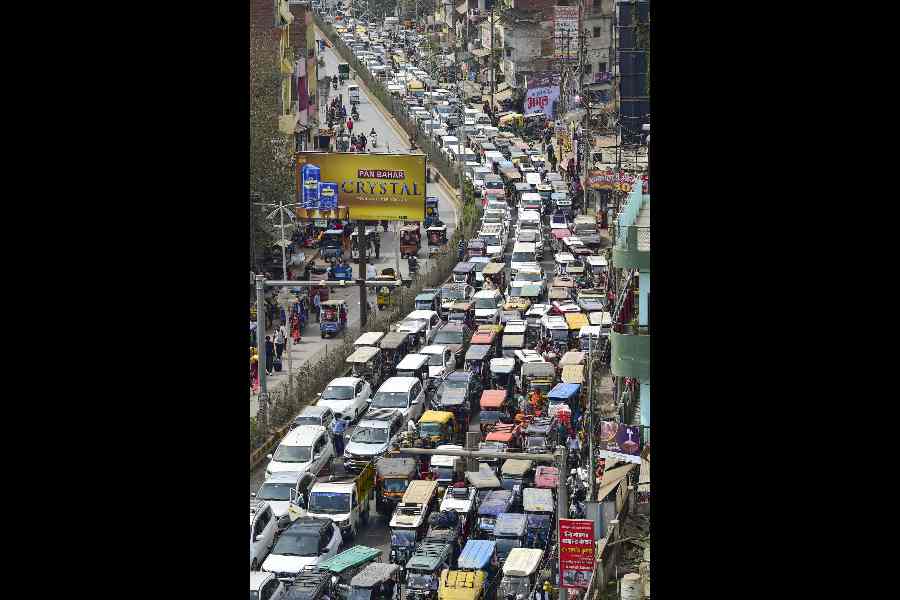

The military insisted that the ouster did not amount to a coup, although it had all the trappings of one, with armored vehicles patrolling the streets. The officers took control of the state broadcaster to announce their action.

Yet remarkably in a continent where deposed leaders often meet grisly fates or flee into exile, Mugabe and his wife were allowed to remain in their sumptuous 24-bedroom home in Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital.

In his final years in power, Mugabe presided over a shattered economy and a fractured political class that was jockeying for influence in anticipation of his death. Although often viewed in the West as a pariah, he was, in many corners of Africa, considered an elder statesman thanks to his liberation pedigree, his longevity and his eloquence in articulating a broad resentment of Western powers’ past and present policies toward the continent.

If Nelson Mandela of South Africa, his contemporary, won universal admiration for emphasizing reconciliation, Mugabe tapped into an equally powerful sentiment in Africa: that the West had not sufficiently atoned for its sins and had continued to bully the continent.

Mugabe had in his early days belonged to a generation of African nationalists whose confrontation with white minority rule fomented guerrilla warfare in the name of democracy and freedom.

But once he won power in Zimbabwe’s first free elections, in 1980, after a seven-year war, he turned, with a blend of guile and brutality, to the elimination of adversaries, real and imagined.

He found them in many places: among the minority Ndebele ethnic group and the clergy; in the judiciary and the independent news media; in the political opposition and other corners of society pushing for democracy; and in the countryside, where white farmers were chased off their land from 2000 onward.

Mugabe morphed into a caricature of dictatorship: vain and capricious, encircled by the flashy spending of his second wife and other family members, who lived in luxury at home and went on shopping sprees and long annual vacations in the Far East. (That wife, the former Grace Marufu, had been his secretary and mistress, and Mugabe, despite a strict Roman Catholic upbringing, fathered two children with her while still married to his first wife, Sally Hayfron.)

“His real obsession was not with personal wealth but with power,” British writer Martin Meredith observed in his book “Our Votes, Our Guns: Robert Mugabe and the Tragedy of Zimbabwe” (2002). As Mugabe declared in June 2008, referring to the opposition Movement for Democratic Change: “Only God, who appointed me, will remove me, not the MDC, not the British. Only God will remove me!”

Robert Gabriel Mugabe was born on Feb. 21, 1924, in Kutama, northwest of Harare, in an area set aside by the white authorities for black peasants. Educated by Catholic missionaries, he was a studious, earnest child who later recalled being happy with solitude as he tended cattle, so long as he had a book under his arm.

His father abandoned the family when Robert was 10, leaving him to deal with a mercurial and emotionally scarred mother, according to “Dinner With Mugabe” (2008), a biography by Heidi Holland.

“The color bar sliced through every domain of society,” he said of his childhood.

His political thought, like Mandela’s, took shape in South Africa at Fort Hare Academy, which he attended on a scholarship from 1950 to 1952, earning the first of a string of degrees in education, law, administration and economics.

“The impact of India’s independence, and the example of Gandhi and Nehru, had a deep effect,” Mugabe said in an interview with The New York Times before Zimbabwe’s independence. “Apartheid was beginning to take shape. Marxism-Leninism was in the air.”

“From then on I wanted to be a politician,” he said.