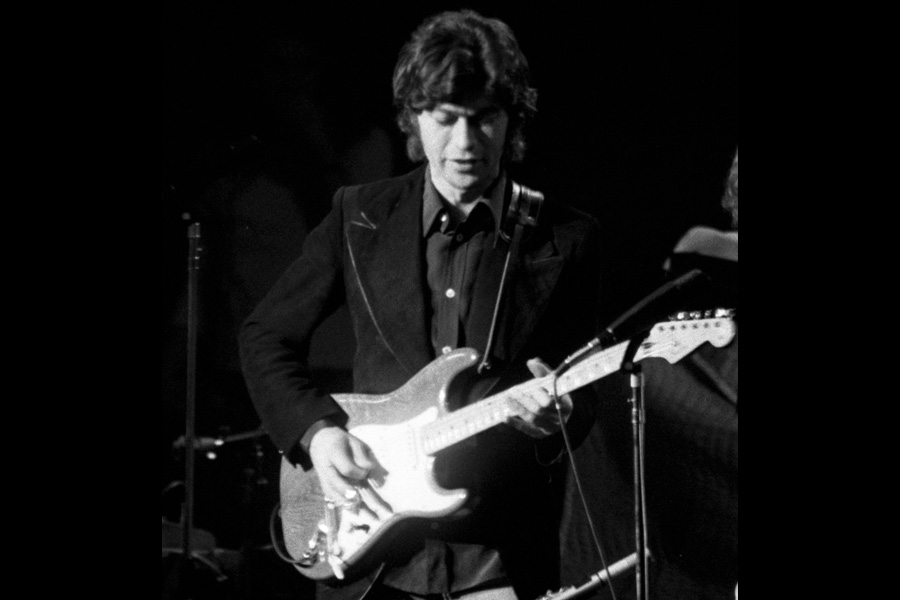

Robbie Robertson, the chief composer and lead guitarist for The Band, whose work offered a rustic vision of America that seemed at once mythic and authentic, in the process helping to inspire the genre that came to be known as Americana, died Wednesday in Los Angeles. He was 80.

His manager, Jared Levine, said he died after a long illness.

The songs that Robertson, a Canadian, wrote for The Band used enigmatic lyrics to evoke a hard and colorful America of yore, a feat coming from someone not born in the United States. With uncommon conviction, they conjured a wild place, often centered in the South, peopled by rough-hewed characters, from the defeated Confederate soldier in “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” to the tough union worker of “King Harvest Has Surely Come” to the shady creatures in “Life Is a Carnival.”

The music he matched to his passionate yarns mined the roots of every essential American genre, including folk, country, blues and gospel. Yet when his history-minded compositions first appeared on albums by The Band in the late 1960s, they felt vital as well as vintage.

“I wanted to write music that felt like it could’ve been written 50 years ago, tomorrow, yesterday — that had this lost-in-time quality,” Robertson said in a 1995 interview for the public television series “Shakespeares in the Alley.”

Speaking of The Band in the 2020 documentary “Once Were Brothers,” Bruce Springsteen said, “It’s like you’d never heard them before and like they’d always been there.”

In its day, The Band’s music also stood out by inverting the increasing volume and mania of psychedelic rock, and also by sidestepping its accent on youthful rebellion. “We just went completely left when everyone else went right,” Robertson said.

The ripple effect of that sound and image — unveiled on The Band’s first album, “Music From Big Pink,” released in 1968 — went wide on impact, landing the group on the cover of Time magazine in 1970 and inspiring a host of major artists to create their own homespun amalgams, from the Grateful Dead’s album “American Beauty” (1970) to Elton John’s “Tumbleweed Connection,” released the next year.

The Band’s music so affected Robertson’s fellow guitarist Eric Clapton that he lobbied for entry into their ranks. (The offer was politely declined.) A quarter-century later, The Band’s music provided a key template for the acts first labeled Americana, including Son Volt, Wilco and Lucinda Williams, as well as for their sonic heirs.

Though Robertson dominated The Band’s writing credits, he frequently emphasized the importance of all five members. “Everybody did something that raised the level of what we were doing to a stronger place,” he told The Guardian in 2019. “They’re all unique characters you could read about in a book,” he told Musician magazine in 1982.

Three of his fellow members — drummer Levon Helm, pianist Richard Manuel and bassist Rick Danko — expressed those characters in distinctly aching vocals, Robertson rarely sang lead, instead finding his voice in the guitar.

A Southern Muse

While the texture of his playing was often flinty, his licks and leads were flush with feeling. In Helm, Robertson found a special muse, as well as a true link to the South; born in Arkansas, Helm was the only member of The Band not born in Canada.

“I know at the time that it seemed strange that somebody from Canada would be writing this Southern anthem,” Robertson told “Shakespeares in the Alley,” referring to “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” which Helm sang. “It took somebody coming in from the outside to really see these things.”

The Bob Dylan connect

The lofty stature of The Band was further burnished by their participation in several seminal events in the history of Bob Dylan. They served as his backing group during the historic 1965-66 tour that found him “going electric,” to the horror of folk fundamentalists who booed his move away from his original acoustic style. “When people boo you night after night, it can affect your confidence,” Robertson told The Guardian. But, he added, “We didn’t budge. The more they booed, the louder we got.”

In “Once Were Brothers,” Dylan called the group “gallant knights” for sticking with him.

In the summer of 1967, The Band went to live with Dylan in Woodstock, New York, where together they recorded a trove of important songs, some of which later leaked out in the form of the first significant bootleg record, nicknamed “The Great White Wonder.” Key songs from those sessions, mainly written by Dylan but augmented by pieces written by members of The Band including Robertson, didn’t enjoy an official release until 1975, as the double album “The Basement Tapes.” It became a Top 10 hit and inspired New York Times critic John Rockwell to call it “one of the greatest albums in the history of American popular music.”

In 1974, The Band reunited with Dylan, backing him on the album “Planet Waves,” which became a No. 1 Billboard hit, and then launching a tour that yielded the gold concert recording “Before the Flood.”

The Last Waltz

Two years later, The Band gave what at the time was called its final concert, held in San Francisco and billed at the time as “The Last Waltz.” An all-star affair, it featured guest artists including Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, Muddy Waters and Neil Young, as well as Dylan. A film of the show, released in 1978 and directed by Martin Scorsese, was lionized by Rolling Stone magazine in 2020 as “the greatest concert movie of all time.” The Band was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1994.

Some years after the group’s demise, in 1987, Robertson began a solo career with an album simply titled “Robbie Robertson.” In the decades that followed, he released four more solo albums, though only the first one went gold.

Most of his post-Band professional efforts were devoted to work in film, often in collaboration with Scorsese, as either a music producer or supervisor or as a composer of scores. The two worked together on noted films like “Raging Bull” and “Casino.” Robertson also served as a music producer or composer on scores of soundtracks for film and television projects, and even did some acting, co-starring with Jodie Foster and Gary Busey in the 1980 film “Carny.”

‘The Guitar Looks Pretty Cool’

Jamie Royal Robertson was born on July 5, 1943, in Toronto. His mother, Rosemary Dolly Chrysler, was a Mohawk who had been raised on the Six Nations Reserve near Toronto. The man whom he believed to be his father and who raised him until he was in his early teens, James Robertson, was a factory worker.

When he was a child, his mother often took him to the Six Nations Reserve where, he told The Guardian, “it seemed to me that everyone played a musical instrument or sang or danced. I thought, ‘I’ve got to get into this club. I said, ‘I think the guitar looks pretty cool.’”

His mother bought him one.

“Rock ‘n’ roll suddenly hit me when I was 13 years old,” he told Classic Rock magazine in 2019. “That was it for me. Within weeks I was in my first band.”

Around that time, his parents separated and his mother told him that his biological father was a Jewish professional gambler named Alexander David Klegerman who had been killed in a hit-and-run accident before she met James Robertson. In his memoir, “Testimony” (2016), Robertson wryly commented on his Indigenous and Jewish heritage.

“You could say I’m an expert when it comes to persecution,” he wrote.

Ronnie Hawkins and The Hawks

His first band, Little Caesar and the Consuls, performed covers of the current hits. A group he joined in 1959, the Suedes, got a crucial break when they were seen by Arkansas-based rockabilly star Ronnie Hawkins.

Hawkins saw enough in Robertson to write two songs with him, which he recorded, and he later invited the teenage guitarist to join his band, the Hawks, initially on bass. The Hawks also included Helm on drums; by 1961, the other future members of The Band were also in the fold. They toured with Hawkins for two more years and recorded for Roulette Records. By 1964, they had gone off on their own as Levon and the Hawks.

Enter Bob Dylan

That group recorded a few singles for Atco, all written by Robertson, and in 1965, he was contacted by Dylan’s management and invited to be part of his backing group. While he initially refused, he did perform with Dylan in New York and Los Angeles, bringing along Helm for those gigs. At Robertson’s insistence, Dylan wound up hiring most of the other future members of The Band for the full tour.

He also invited Robertson to perform on a session in 1966 for his album “Blonde on Blonde.” The next year, he asked the Hawks to move to his new base in Woodstock, where they rented a house later known as Big Pink. It was there they recorded the music later released as “The Basement Tapes” as well as what became “Music from Big Pink.”

“It was like a clubhouse where we could shut out the outside world,” Robertson wrote in his memoir. “It was my belief something magical would happen. And some true magic did happen.”

The Weight

When “Music From Big Pink” was released in the summer of 1968, it boasted seminal songs written by Robertson such as “The Weight” and “Chest Fever,” along with strong pieces composed by other members of The Band and by Dylan. “This album was recorded in approximately two weeks,” another close Dylan associate, Al Kooper, wrote in a review in Rolling Stone. “There are people who will work their lives away in vain and not touch it.”

For The Band’s follow-up album, “The Band,” released in 1969, Robertson either wrote or co-wrote every song, including some of his most enduring creations, among them “Up On Cripple Creek,” “Rag Mama Rag,” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” which became a Top Five Billboard hit in a version recorded by Joan Baez. The album reached No. 9 on the magazine’s chart.

The Band’s next effort, “Stage Fright,” released in 1971, shot even higher, peaking at No. 5, buoyed by Robertson compositions like the title track and “The Shape I’m In.” Those songs, like many on the album, expressed deep anxiety and doubt, a theme that carried over to “Cahoots,” released in 1972. And while that album broke Billboard’s Top 20, it wasn’t as rapturously received as its predecessors.

A collection of blues and R&B covers, “Moondog Matinee,” was released in 1973, and Robertson’s muse fully returned in 1975 on the album “Northern Lights — Southern Cross,” which included “Acadian Driftwood,” his first composition with a Canadian theme. The original group’s final release, “Islands” (1977), consisted of leftover pieces and was issued mainly to fulfill the group’s contract with its label, Capitol Records.

Neil Diamond

The same year as “The Last Waltz,” Robertson produced a Top Five platinum album for Neil Diamond, “Beautiful Noise,” and a double live album by Diamond, “Live at the Greek,” which made Billboard’s Top Ten and sold more than two million copies.

Robertson told Musician magazine that he broke up The Band because “we had done it for 16 years and there was really nothing else to learn from it.” Another strong factor was Robertson’s frustration over hard drug use by most of the other members.

The Band without Robbie

Without Robertson, the other members of The Band released three albums in the 1990s; the last, “Jubilation” in 1998, was without Manuel, who had died by suicide 12 years earlier. Danko died of heart failure in 1999, Helm of throat cancer in 2012.

Over the years, other members of The Band accused Robertson of taking more songwriting credits than he deserved. To them, it was a cooperative effort, with the other members adding important arrangements and contributing elements that helped define the essential character of the recordings. Helm was particularly vociferous in his condemnation, amplified by his furious 1993 memoir, “This Wheel’s on Fire.”

In his own memoir, Robertson wrote of Helm, “it was like some demon had crawled into my friend’s soul and pushed a crazy, angry button.”

Killers of the Flower Moon

Robertson’s final solo album appeared in 2019 with a title, “Sinematic,” that underscored his devotion to film work in the last four decades of his life. He recently completed the score for his 14th film project, Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon,” which is scheduled to be released this fall.

Robertson is survived by his wife, Janet; his children, Alexandra, Sebastian and Delphine; and five grandchildren.

Marveling over where life had taken him, Robertson once told Classic Rock magazine, “People used to say to me, ‘You’re just a dreamer. You’re gonna end up working down the street, just like me.’ Part of that was crushing and the other part is, ‘Oh yeah? I’m on a mission. I’m moving on. And if you look for me, there’s only going to be dust.’”

The New York Times News Service