Saturday, May 6, 2023, is the day when Charles III and his wife, Camilla, will be crowned king and queen of the United Kingdom.

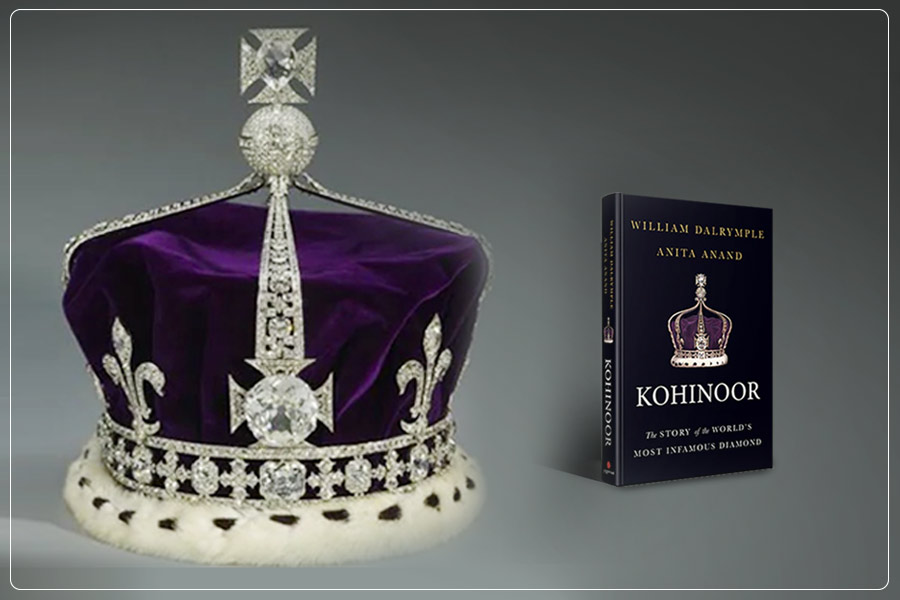

In a step away from tradition, the queen consort will not wear the Koh-i-Noor diamond (also spelled Kohinoor and Koh-i-Nur) on her crown so as to not offend "political sensitivities," a royal source told British media.

The diamond, which is rumored to be unlucky for male wearers, has always been worn by women. It was first worn by Queen Victoria in the form of a brooch and circlet, then by the Queen Consorts Mary and Alexandra, and finally by Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

Camilla's gesture of not wearing the diamond for the coronation is a big one. But why? What makes the diamond such an important historical artifact?

The story of the Koh-i-Noor

The 105-carat diamond, which was a 190-carat piece before it reached the British, has a long history of conquest. The Koh-i-Noor was an oddly-shaped gem. "It resembled a large hill or perhaps a huge iceberg rising steeply to a high, domed peak," William Dalrymple and Anita Anand write in their 2017 book "Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond."

The diamond was first mentioned by Persian historian Muhammad Kazim Marvi, who documented the warrior Nader Shah's invasion of India in the mid-18th century.

Scholars are unsure where the gemstone originated from, but it is widely believed that it was sifted from the alluvial sands of Golconda, in southern India. It fell into the hands of marauding Turks around the Early Middle Ages and then into the hands of several Islamic dynasties in India, before landing in the hands of the Mughals.

They, in turn, lost it to the Persian warlord Nader Shah, who christened it Koh-i-noor, or the mountain of light. Nader Shah transferred it to his Afghan bodyguard, Ahmad Shah Abdali, and it remained in Afghan hands for a hundred years before Ranjit Singh, the king of Punjab, extracted it from a fleeing Afghan in 1813.

After the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839, Punjab fell into disarray, enabling the East India Company to conquer the kingdom. Ranjit Singh's 10-year-old son, Duleep Singh, was taken into British custody. In 1855, the Koh-i-noor was handed over by Duleep Singh's guardian, Sir John Spencer Login, to Dalhousie, the governor-general of India.

Wanting to document the history of the gemstone before presenting it to the queen, Dalhousie commissioned a young officer, Theo Metcalfe, with researching and writing a history of the diamond.

From then on, the diamond rose in fame, reaching its peak after Queen Victoria had it displayed in England. "It was a symbol of Victorian Britain's imperial domination of the world and its ability […] to take from around the globe the most desirable objects and to display them in triumph," Anand and Dalrymple write in their book.

In addition to India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran also lay claim to the diamond.

Symbol of British imperialism

Even today, the Koh-i-noor retains its fame and its reputation as a symbol of British conquest, which is a big part of why Indians are demanding its return.

"There have been various calls for the diamond's return to India, from policymakers, activists and cultural heritage experts," said Anuraag Saxena, a Singapore-based activist and founder of the India Pride Project, which has been campaigning for the restitution of Indian cultural artifacts. "We argue that the diamond and other looted heritage should be returned as a symbol of historical injustice."

There have also been demands from other Indian activists for the diamond to be brought back from India. "When Queen Elizabeth died, in one of the processions, I saw the crown with the Koh-i-Noor in it," said Venktesh Shukla, a San Francisco-based venture capitalist of Indian origin, adding that he was so irritated by the display that he launched a petition on Change.org for the diamond's restitution.

"They should be ashamed of what they did, of how they got the Koh-i-Noor. And instead of being ashamed, they're showing off," he continued, adding that it was arrogant of the UK to display the gem.

Most recently, in October 2022, Arindam Bagchi, spokesman for the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, said the government would "continue to explore ways and means for obtaining a satisfactory resolution of the matter."

This came after the Indian government said in 2016 that the diamond was a gift to the British.

However, Shukla said he feels this needs to be a grassroots movement focusing on educating the British about their colonial heritage. His petition has gathered over 9,600 signatures, but it remains to be seen whether his initiative and that of the Indian government will actually bear fruit.

Imperialist traditions

At the moment, Buckingham Palace's decision to stay away from the diamond seems to be a compromise between "reflecting tradition" and "being sensitive to the issues around today," according to an unnamed royal who spoke to the Daily Mail.

But the palace's sensitivity seems to be limited to the Koh-i-Noor: the queen-consort's crown will feature the Cullinan diamonds instead, gemstones that were mined from South Africa and are another symbol of British imperialism.

This hardly suggests a genuine desire to change. Even in the past, British politicians have emphasized their unwillingness to return cultural artifacts.

In 2013, David Cameron, the prime minister at the time, famously remarked that he was against "returnism" when it came to restituting the colonial diamond.

Imperial institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum, which house thousands of artifacts stolen from colonized countries, have also resisted demands to return the loot.

"Returning our artifacts might be one simple act of the British atoning for the sins of their morbid colonial past," the activist Saxena argued, adding that the US, Germany, France, Canada and Australia are all doing the same.

"Isn't it time," he asked, that "the UK caught pace with the rest of the world?"