They call it Democracy III. In this game you get to play head of a state. As you click on the tab that reads Play Game, you are welcomed by a screen that has a list of countries. Every country has a detailed chart with information on population, life expectancy, gross domestic product, per capita income and so on and so forth. After you pick your country, you get to name your political party and choose the length and limits of your term of office.

Democracy III is one of the 16 interactive video games that are on display at the Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan. This is part of Global Games: Games And Politics, an ongoing exhibition of political video games created since 2004 and developed by the Goethe-Institut and the Germany-based ZKM (Center for Art and Media).

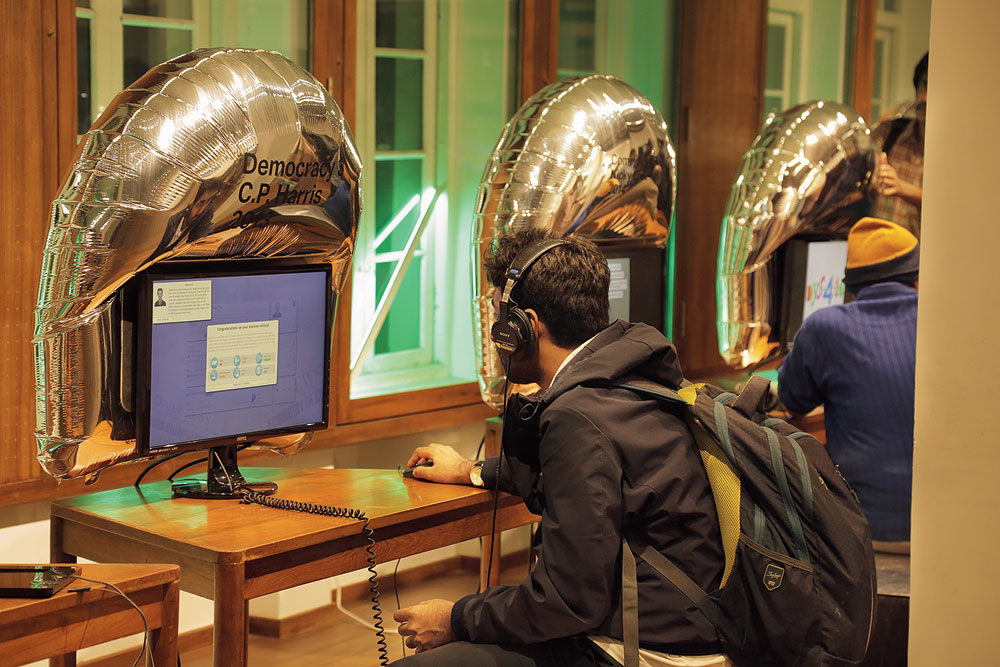

The huge hall at the Goethe-Institut is lined with monitors. Each monitor has a silver balloon perched atop; it lends a futuristic touch, very Star Trek. One can see the occasional figure bent over a monitor, headphones in place, clicking away. I pick a country, Canada, and a message flashes on the screen: “Congratulations! Welcome to your new job as Prime Minister. The lives of all 3,34,76,000 citizens are now in your hands.”

There are tabs titled GDP, Poverty, Health, Education, Unemployment, Crime. Alter any one and the change impacts the rest. One also gets to pick from a list of natural calamities during one’s tenure — hurricanes, earthquakes. Crime, unemployment, national debt, terrorism, climate change are other heads that appear onscreen as the game progresses. Detailed data tables, diagrams and trend indicators are available at a click to aid decision-making.

There are 21 categories of citizens listed under a country — farmers, industrialists, liberalists, capitalists, the youth and the retired, to name a few. Every decision is applauded by some and rejected by others — indicated by colour codes — and you realise you can never please all the people. The goal could be either to get re-elected or to turn your country from a liberal to a conservative state.

Into the first 10 minutes of my term as Prime Minister of Canada, I tighten the environmental laws and increase fines for violators. The effect on the environment is positive, but the GDP plummets. The next thing I know is that the number of unemployed people is rising, and thereon all starts to go haywire.

According to Friso Maecker, the director of Max Mueller Bhavan, Calcutta, he had wanted to host an art exhibition that would be “relevant” across age groups. He says, “Video games are played by all age groups. They have entered peoples’ living rooms and are not hushed away into a dark corner anymore.

So this exhibition deals with a medium that many people use in their everyday lives.”

Speaking of relevance, the game Orwell begins with a blast. The context of the game: on April 12, 2017, a bomb explodes in the populated Freedom Plaza in Bonton, Germany, destroying an important statue and killing several people. A note containing the first three stanzas of the German folk song Die Gedanken sind frei or The Thoughts are Free is found at the site. Present at the Plaza shortly before the explosion was Cassandra Watergate, an artist who was arrested for assaulting a police officer at a protest some weeks ago. As a player, I have to investigate the case; it involves surveillance. As the game unfolds, it penetrates the most private aspects of citizens’ lives — their surfing habits, call details, where they shop, who they socialise with, their personal milestones.

Maecker suggests that the experiential nature of the games might move individuals to an informed understanding of the world they are living in. He says, “It is the nature of the video game that it tries to blur the lines between real and fiction. While playing, one needs to take decisions for the character one becomes in the game, thus experiencing and understanding a whole range of political systems.”

The 2016 game Yellow Umbrella recreates blockades complete with tear gas-wielding police, thugs, a politician and regular citizens. Unmanned, which is from 2012, is about the effects of drone warfare from a pilot’s perspective. And then there is This War of Mine, a war game that shows the consequences of armed conflict through a civilian’s experience. It was developed in 2014.

Not every game has to do with the politics of the state, there are those that explore gender politics too. A student of Loreto College, Illanjana Bhadra, has played two games — Coming Out Stimulator and Dys4ia. While the first chronicles the challenges an individual faces after having decided to come out, the second plays out a narrative about a person going through sex change. Bhadra hopes such gender sensitive games will foster a spirit of empathy and inclusiveness. Till then they make for some great gaming.