She has not seen her husband, the new Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ales Bialiatski, since a few days before his arrest in July 2021, and still has not been told when and for what he will be put on trial.

Their letters to each other sometimes get delivered but, for long periods, don’t arrive.“I dare not say what that this award might mean,” Natalia Pinchuk, Bialiatski’s wife, said in a telephone interview from Minsk, the Belarusian capital after he was announced as one of the prize’s2022 recipients on Friday.

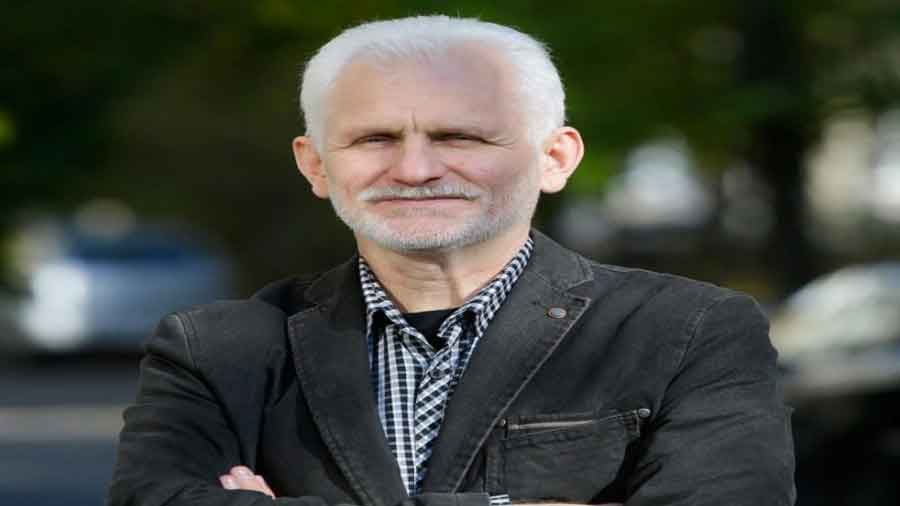

“Of course, I have hopes, but I’m afraid to express them. There is always this fear.” Though not widely known in the West, Bialiatski, 60, has been a pillar of the human rights movement in eastern Europe since the late 1980s, when Belarus was still part of the Soviet Union but, inspired by the reforms of Mikhail S.Gorbachev in Moscow, was slowly shaking off decades of paralysing fear.

He was active in Tutajshyja, or “The Locals,” a dissident organisation that helped lay the groundwork in the late Soviet period for a movement calling for the independence of Belarus.

After the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union and the 1994 election of Belarus’s authoritarian leader, President Aleksandr G. Lukashenko, Bialiatski helped found and lead Viasna, or Spring, a rights group whose members are now nearly all in prison or living in exile abroad.

He served for a time as the director of a museum honouring Maksim Bahdanovic, a poet who is considered a founder of modern Belarusian literature. Still, He was forced out of that post when Lukashenko, who has now been President for 28 years, started cracking down on the Belarusian language and promoting Russian. Andrei Sannikov, a long-time friend of Bialiatski’s, hailed the Nobel Peace Prize as an “extremely important” boost to “all of us who have been fighting for human rights and human dignity” in Belarus.

New York Times News Service