Publisher Puffin UK announced on Friday that it would publish original Roald Dahl texts unedited under its adult Penguin logo, following a week of criticism over edits it had made to the 20th-century author's children's books.

"By making both Puffin and Penguin versions available, we are offering readers the choice to decide how they experience Roald Dahl's magical, marvelous stories," Francesca Dow, managing director of Penguin Random House Children's, said.

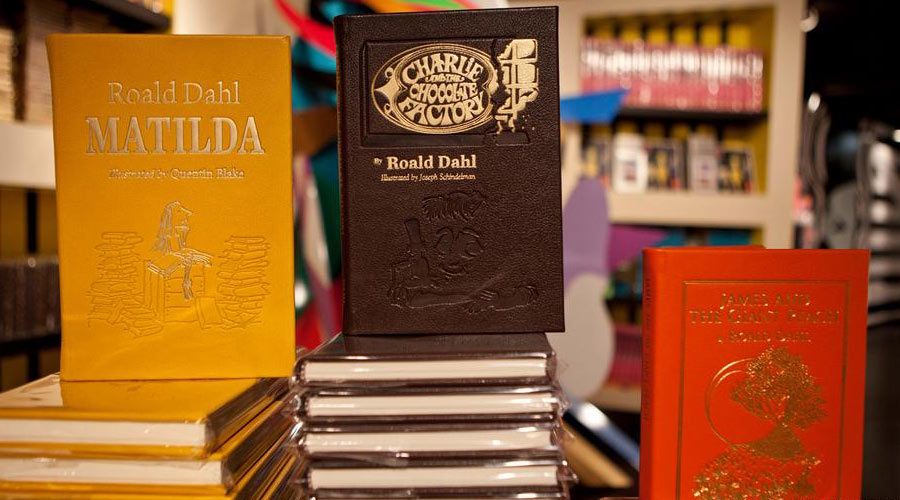

The originals would be dubbed the "Roald Dahl Classic Collection" and published individually, Penguin said. The Welsh-born author with Norwegian parents, whose first big hit was published in 1961, has sold more than 250 million copies worldwide and inspired numerous TV and film adaptations.

What was all the fuss about?

Renowned author Salman Rushdie, the PEN writers' organization, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and even Queen Consort Camilla had appeared to be among those weighing in on softening Dahl's choice of wording in recent days.

Passages relating to weight, mental health, gender and race were altered in several books such as the 1964 release "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory."

In that, for instance, Augustus Gloop — "the great big greedy nincompoop" and chocolate-addicted young boy — was described not as "enormously fat," but instead as "enormous." The Oompa-Loompas singing that nincompoop line are now gender neutral, as the "Cloud-Men" in "James and the Giant Peach" are now "Cloud-People."

Another descriptor removed was "ugly;" Mrs. Twit in "The Twits" is now "beastly."

In a 1983 book, "The Witches," a supernatural woman posing as an ordinary person is said to adopt an appearance that could make her pass for a "top scientist or running a business," rather than a "cashier in a supermarket or typing letters for a businessman."

The alterations come soon after the rights to Dahl's stories were sold to Netflix, with a view to making modern-era renditions of books already tackled by film directors like Steven Spielberg (The BFG) and Tim Burton (Charlie and the Chocolate Factory).

'Dahl was no angel, but this is absurd censorship'

Although it's not part of his children's fiction, Dahl was also known for antisemitic comments made in later life, first in an interview and then a published article soon before his death in which he said he had "become an anti-Semite." The Roald Dahl Story Company apologized for this past in 2020, three decades after his death.

British author Salman Rushdie, who lived in hiding for years because of an Iranian fatwa calling for his death over the 1988 book "The Satanic Verses," said Dahl had been a "self confessed anti-Semite, with pronounced racist leanings, and he joined in the attack on me back in 1989."

Nevertheless, Rushdie wrote on Twitter: "Roald Dahl was no angel but this is absurd censorship. Puffin Books and the Dahl estate should be ashamed."

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said the books should not be "airbrushed," and Queen Consort Camilla even appeared to obliquely comment on the controversy, telling members of her online book club to "please remain true to your calling, unimpeded by those who may wish to curb the freedom of your expression or impose limits on your imagination."

A spokeswoman for the French publishers of Dahl's work, Gallimard, told the AFP news agency that "this rewrite only concerns Britain."

"We have never changed Roald Dahl's writings before, and we had no plans to do so today," she said.

"We've listened to the debate over the past week which has reaffirmed the extraordinary power of Roald Dahl's books and the very real questions around how stories from another era can be kept relevant for each new generation," Francesca Dow of Penguin Random House Children's said on Friday, but added:

"As a children's publisher, our role is to share the magic of stories with children with the greatest thought and care. Roald Dahl's fantastic books are often the first stories young children will read independently, and taking care for the imaginations and fast-developing minds of young readers is both a privilege and a responsibility."

Darker stories from tougher times

Born in 1916, Dahl had fought in World War II as a fighter ace, then worked as a diplomat and intelligence officer after being invalided out of combat. He had lived through post-war rationing in the UK, including with small children, and he lost a young daughter to measles around the most prolific point of his writing career in the 1960s.

His stories often reflected these challenges and these conditions, and he would frequently tap into emotions like fear and sadness to connect with children in his texts.

Many child protagonists in his stories suffer under cruel foster carers or distant relatives (James and his aunts) or live in extreme poverty (Charlie with his loving family) or are orphans (Sophie in the BFG) or are fighting for survival (Fantastic Mr. Fox and his family).

The entire premise of one book, "George's Marvelous Medicine" — which admittedly starts with a "don't try this at home, kids" disclaimer — is George getting revenge on his wicked grandmother by concocting a cocktail using whatever he can find around the house to create a probably poisonous substitute for her medicine.

And in the BFG, for several chapters the only clue readers have that young Sophie being kidnapped is not going to end up with her being eaten by her giant captor is the title of the book.

The word "Dahlesque" is even in the Oxford English Dictionary, whose definition specifically notes "his children's works featuring eccentric plots, villainous or loathsome adult characters, and dark humor."

This use of more macabre images, usually with happy endings if you stayed the course, was also noted by some critics.

Laura Hackett, deputy literary editor of The Sunday Times newspaper, had called the changes "botched surgery" and said she would hold on to her original copies so her children could "enjoy them in their full, nasty, colorful glory."