A supervisor urged surgeons at Columbia University Irving Medical Centre in Manhattan to volunteer for the front lines because half the intensive-care staff had already been sickened by coronavirus.

“ICU is EXPLODING,” she wrote in an email.

A doctor at Weill Cornell Medical Centre in Manhattan described the unnerving experience of walking daily past an intubated, critically ill colleague in her 30s, wondering who would be next.

Another doctor at a major New York City hospital described it as “a petri dish”, where more than 200 workers had fallen sick. Two nurses in city hospitals have died.

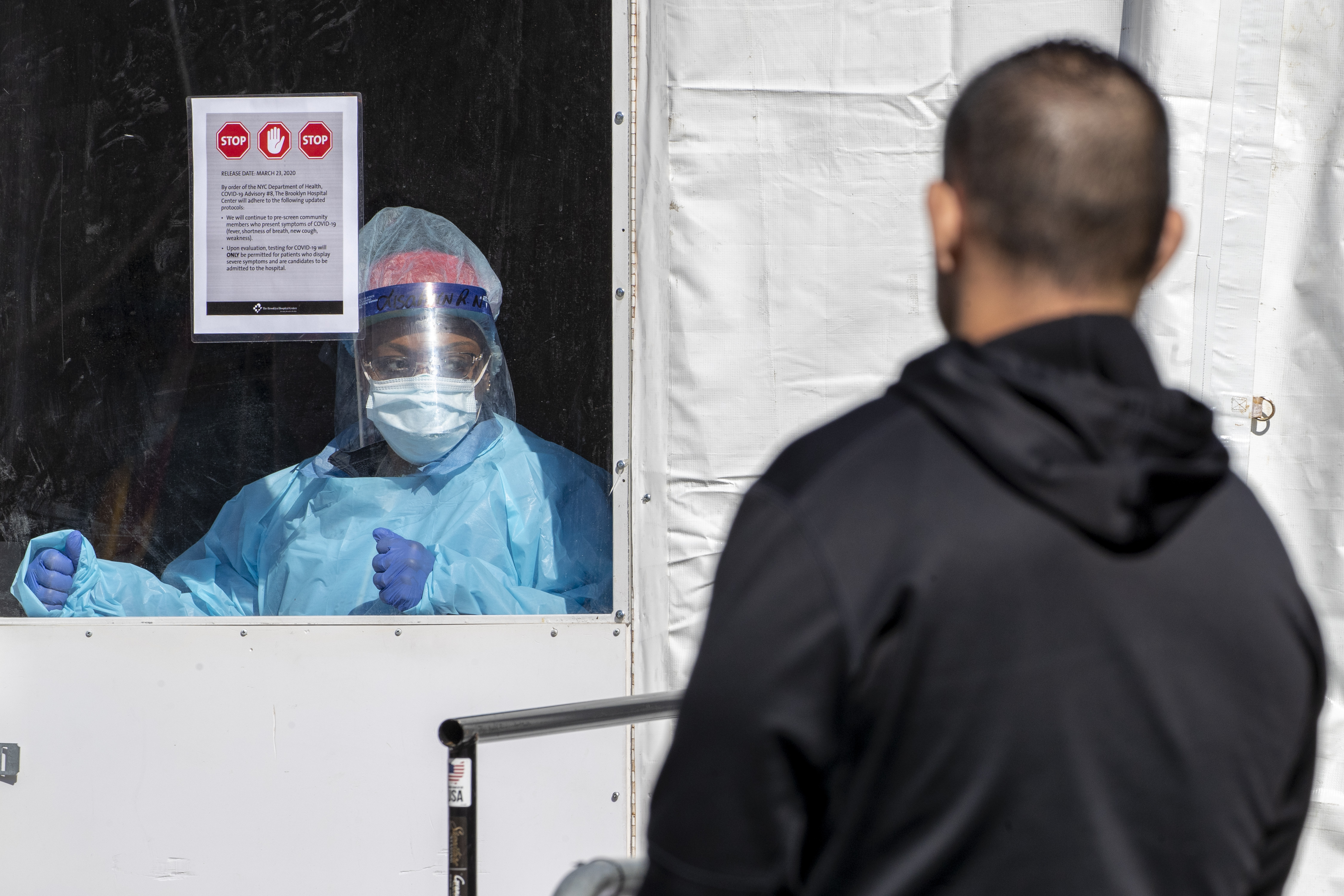

The coronavirus pandemic, which has infected more than 30,000 people in New York City, is beginning to take a toll on those who are most needed to combat it: the doctors, nurses and other workers at hospitals and clinics. In emergency rooms and intensive care units, typically dispassionate medical professionals are feeling panicked as increasing numbers of colleagues get sick.

“I feel like we’re all just being sent to slaughter,” said Thomas Riley, a nurse at Jacobi Medical Centre in the Bronx, who has contracted the virus, along with his husband.

Medical workers are still showing up day after day to face overflowing emergency rooms, earning them praise as heroes. Thousands of volunteers have signed up to join their colleagues.

But doctors and nurses said they can look overseas for a dark glimpse of the risk they are facing, especially when protective gear has been in short supply.

In China, more than 3,000 doctors were infected, nearly half of them in Wuhan, where the pandemic began, according to Chinese government statistics. Li Wenliang, the Chinese doctor who first tried to raise the alarm about Covid-19, eventually died of it.

In Italy, the number of infected heath care workers is now twice the Chinese total, and the National Federation of Orders of Surgeons and Dentists has compiled a list of 50 who have died. Nearly 14 per cent of Spain’s confirmed coronavirus cases are medical professionals.

New York City’s health care system is sprawling and disjointed, making precise infection rates among medical workers difficult to calculate.

A spokesman for the Health and Hospitals Corporation, which runs New York City’s public hospitals, said the agency would not share data about sick medical workers “at this time”.

William P. Jaquis, president of the American College of Emergency Physicians, said the situation across the country was too fluid to begin tracking such data, but he said he expected the danger to intensify.

“Doctors are getting sick everywhere,” he said.

Last week, two nurses in New York, including Kious Kelly, a 48-year-old assistant nurse manager at Mount Sinai West, died from the disease; they are believed to be the first known victims among the city’s medical workers. Health care workers across the city said they feared many more would follow.