It was nearly 3am in the mountainous borderlands of eastern Afghanistan when a deafening thud jolted Qudratullah awake. Confused, he staggered to the doorway of his mud brick home, looked outside and froze.

Thick plumes of black smoke and dust filled the air. The front of the modest house where his relatives lived was a pile of rubble. His 3-year-old nephew stood in the yard, sobbing. Behind him, four more children were sprawled across the pale earth, their lifeless frames soaked in blood.

Qudratullah ran towards them, he said. Then another blast struck.

His village, Mandatah, was one of four in eastern Afghanistan hit this month by Pakistani airstrikes, Afghan officials said, killing at least 45 people, including 20 children.

Among them were 27 of Qudratullah’s relatives — an almost incomprehensible loss. Qudratullah, 18, who like many in Afghanistan goes by only one name, lost his 16-year-old wife, who was crushed beneath a pile of rubble in the second airstrike. His older brother, who survived, lost all four of his daughters, all under 11.

“I’m devastated,” Qudratullah said. “I lost my wife, my relatives, our home, our vehicles, our animals, everything.”

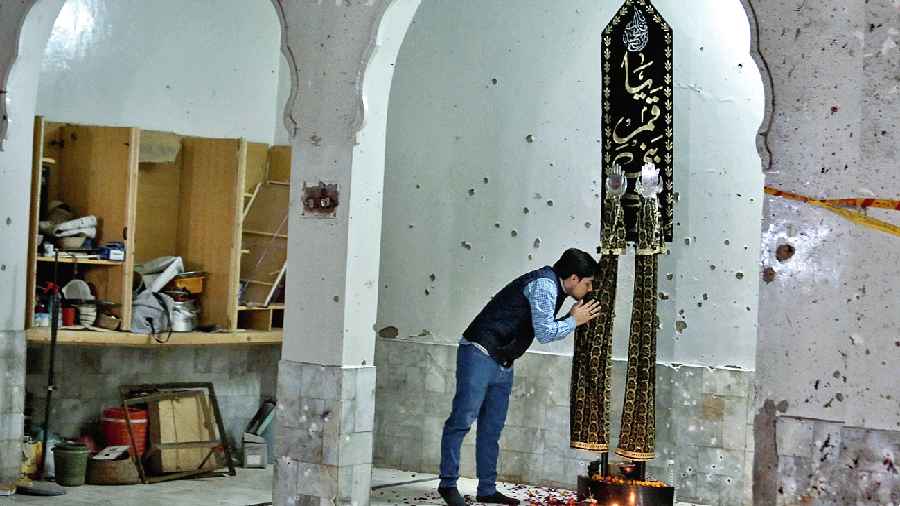

The pre-dawn airstrikes in Khost and Kunar provinces two weeks ago marked a serious escalation of the cross-border conflict in this remote, wild and rocky stretch of Afghanistan, and exacerbated tensions between the two countries that have navigated a delicate relationship since the Taliban seized power last year.

Qudratullah’s brother Sarbaz Ji, 25, was wounded and taken to a hospital in Maton, the capital of Khost province.

Pakistani officials have not confirmed or commented on the airstrikes.

The airstrikes, which Afghan officials said were carried out by Pakistani military aircraft, came several days after militants said to be operating from the area killed seven soldiers across the border in Pakistan.

In eastern Afghanistan, many feared that the carnage of the recent airstrikes was the beginning of a violent new chapter of the long-running conflict in the tribal lands that spill across the porous border. Reinforcing those concerns, Afghanistan’s acting minister of defence, Mullah Muhammad Yaqoob, warned in a speech on Sunday that the Taliban government would not tolerate any more “invasions” from neighbouring countries on Afghan soil.

“Pakistan sending in manned aircraft and killing so many people in different places, the Taliban’s defence minister threatening war if there are more attacks — this is a turning point,” said Asfandyar Mir, a senior expert at the US Institute of Peace.

For over a decade, Pakistani authorities have sought to stamp out the militants hostile to the Pakistani state in Afghanistan’s borderlands, sporadically hitting the area with artillery that have killed a handful of civilians each year.

After the Taliban toppled the western-backed government in Afghanistan, many in Pakistan hoped that the insurgents turned rulers — who benefited from Pakistan’s support over the past 20 years of war — would rein in the violence by the militants, known as Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan or the Pakistani Taliban.

But in recent months, attacks by the group in Pakistan have surged: Since the western-backed Afghan government collapsed in August, the Pakistani Taliban have carried out 82 attacks in Pakistan, more than double the number over the same period of the previous year, according to the Islamabad-based Pak Institute of Peace Studies. The attacks killed 133 people.

Those numbers are still relatively low compared with the height of the Pakistani Taliban’s insurgency around 2009, but the recent sharp increase in violence has fuelled fears that the group is gaining strength after having declined over the past decade, and has reinforced concerns that Afghanistan under the new Taliban government could become a haven for militants.

Taliban officials have denied providing safe haven for militants, including the Pakistani Taliban, but the issue has become a flash point between Afghan and Pakistani authorities, who claim that the militant group — which is responsible for some of the worst terrorist attacks in Pakistan’s history — has become emboldened under the new Taliban government and allowed to operate freely on Afghan soil.

The Pakistani Taliban, which analysts estimate to have several thousand fighters in eastern Afghanistan, have maintained ties with the Taliban for over a decade and pledged allegiance to the Taliban leader. Hundreds of jailed Pakistani Taliban militants were released from prison last year as the Afghan Taliban seized control of major cities and liberated their prisons.

“It would be fair to describe the TTP as the ideological twin of the Afghan Taliban,” said Madiha Afzal, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, using the abbreviation for Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan. “When the Taliban took over Afghanistan last year, the TTP hailed the Taliban’s ‘victory’ and renewed its oath of allegiance.”

The glint of a barbed-wire fence dividing Pakistan and Afghanistan is visible just over the horizon. The border, known as the Durand Line, cuts directly through traditional Pashtun lands and for decades was little more to families divided on either side than a line drawn across the maps of British colonial officers.

The fence itself has been a source of tension between the two countries.

When the Pakistani military launched a sweeping military offensive against militants in 2014, hundreds of thousands of people fled the fighter-bombers pounding Pakistan’s tribal areas and crossed into Afghanistan, seeking shelter with relatives.

Among them were many militants with the Pakistani Taliban, who found refuge among the Taliban.

For years, they quietly regrouped amid the threat of American airstrikes and offensives by western-backed Afghan security forces. But since the Taliban seized power last year, many militants, now able to move freely, have returned to their relatives’ homes along the border, residents say.

New York Times News Service